Sanctifying the Ordinary: A Mother-Artist’s Journey Through the Holy and Mundane

An Interview with Lee Nowell-Wilson

Editor’s Note: The following conversation between visual artist and founder/editor of MILKED, Lee Nowell-Wilson, and Jess Sweeney, visual artist and the Collegium Institute’s Ars Vivendi Arts Initiative director, embodies several virtues: from ecumenical Christian dialogue between two women of faith, one Orthodox, the other Roman Catholic, with a focus on what unites us; to keenly attentive interior awareness of movements of the Holy Spirit in art and faith; to mutual support between mothers who also live fruitful creative practices; to a healthy balance among forms of self-gift and development of various God-given talents within each individual life in its family and social contexts. Like any interview, it has been very lightly edited for length and clarity. —KC

Jess Sweeney: Your artist’s statement really captures the energy and ethos of what you're doing: You write that you’re a figurative artist who explores and documents the mundane, humorous, overloaded, holy, tender aspects of daily domestic life. So I’m wondering if you could expand on that a little bit and sort of talk about what compelled you to focus in on this space, the domestic space.

Lee Nowell-Wilson: Thank you for that sweet compliment. I think that I’d like to start with sharing that my work has always been pretty autobiographical. Pretty much since, you know, you first start drawing in elementary school and then it matures as you get into high school and then you realize you want to go to college for it. I feel like it’s pretty natural for those early phases to be autobiographical as you’re trying to figure out who you are, but that type of biography essence kind of stuck with me all the way through, even post-graduating. And any time that I tried to really paint something else that was a bit more outside myself, it didn’t connect or just kind of felt like I was trying to step into somebody else’s shoes.

So I think that’s related to my heart—to have my paintings be a wrestling ground for what I’m trying to just work out in my own heart with the Lord, or with some sort of relational thing in my life. Painting has always been a wrestling mat for me, and [it] is where I kind of try and subconsciously figure out a lot that’s going on internally, whether it’s philosophically or theologically or personally. It’s essentially like trying to step into a direct conversation with something that’s inside me, but ultimately bigger than myself.

JS: It almost seems that visual art in particular has this kind of incarnational aspect to it: the way in which you take these interior, hidden aspects of yourself and then bring them into the visual and incarnate them that way. The way that you articulated your process made me think of that.

LNW: Right, yes! And so when I became a mother in 2017, it felt really natural for my work to make a big shift towards investigating the maternal mind. It wasn’t necessarily because I thought the maternal mind isn’t being represented or because I wanted to make a statement like that; it wasn’t anything political. It was more a yearning in my own heart to kind of process this huge shift that had happened in my own heart and my own mind.

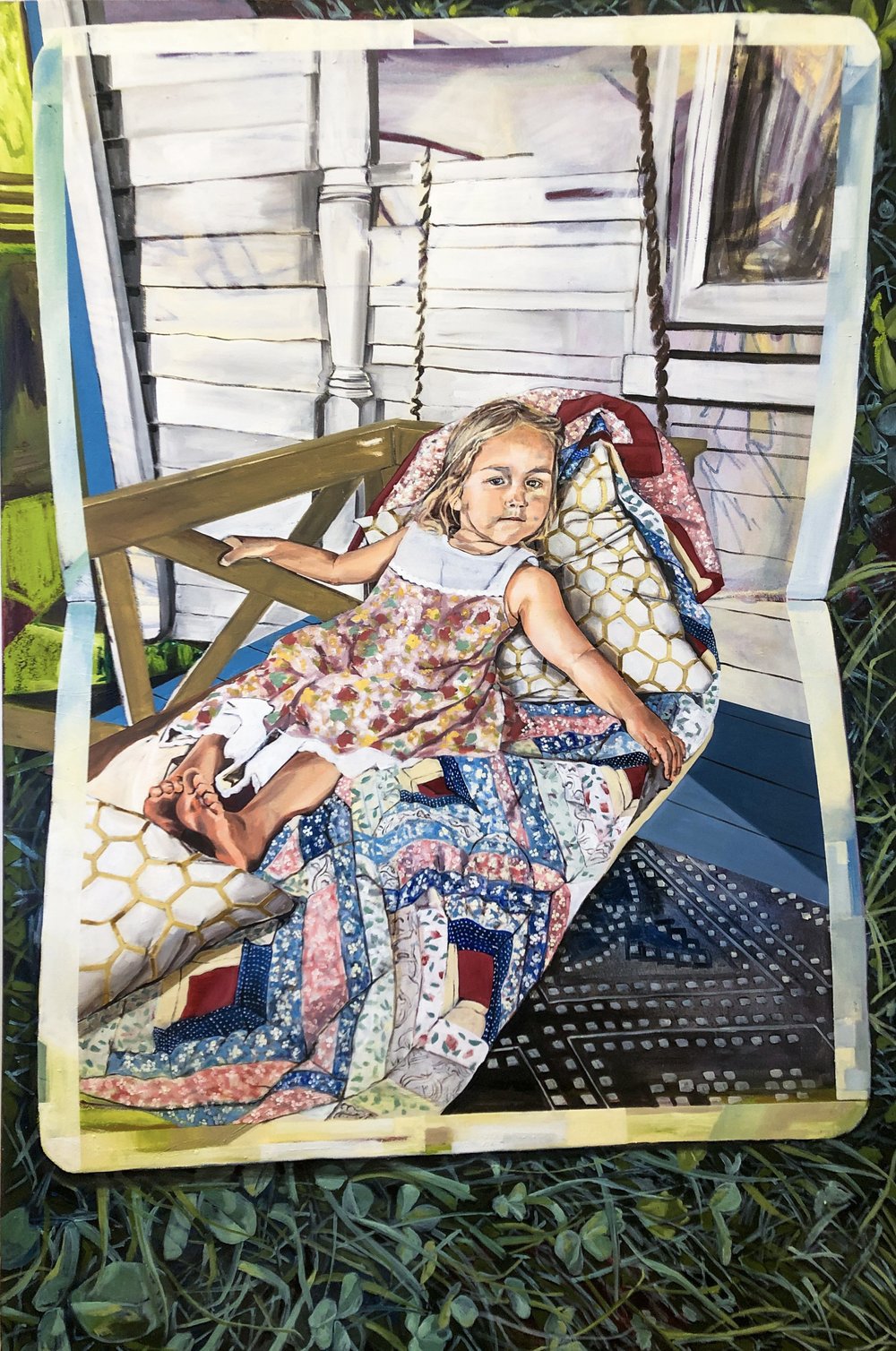

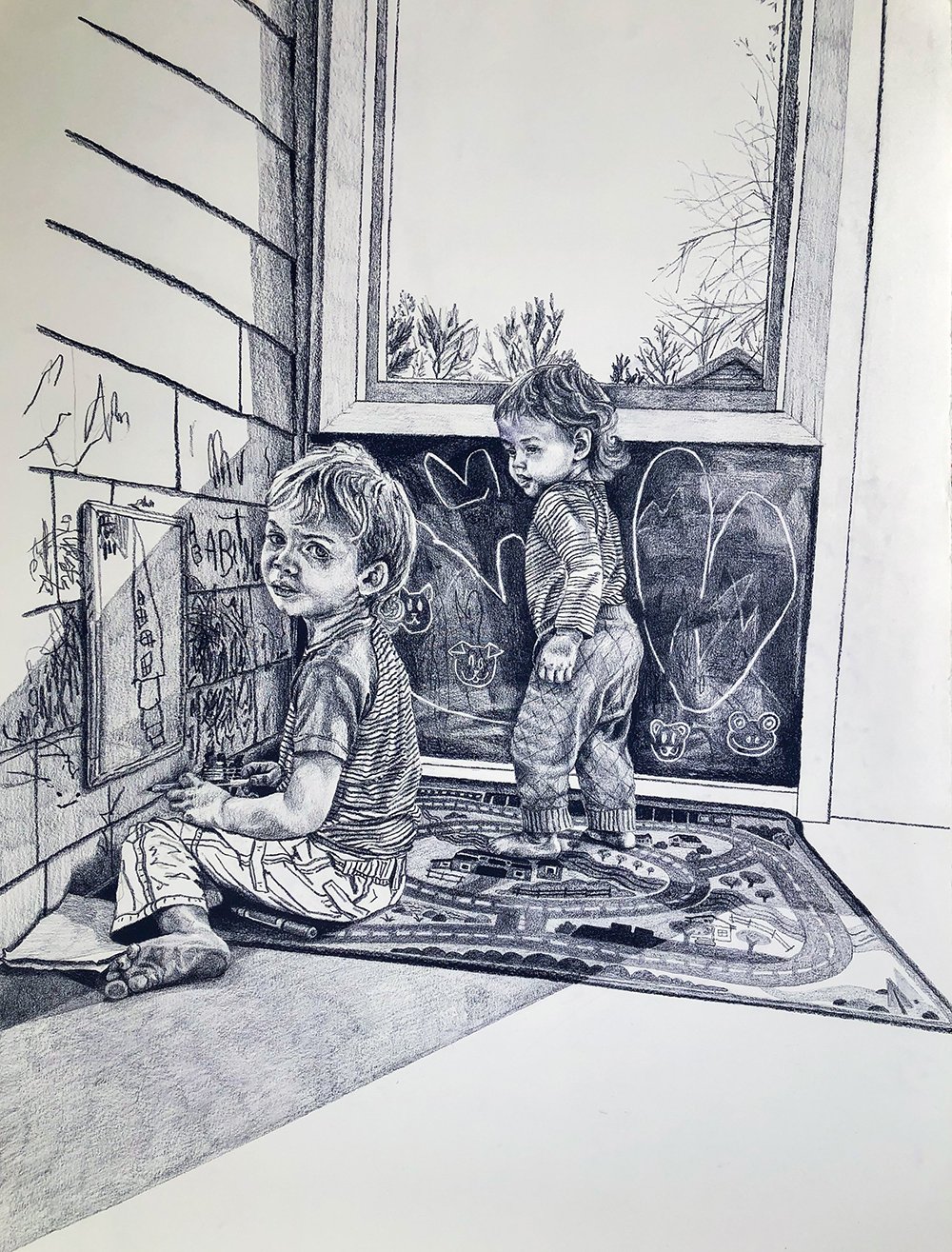

And it’s funny to me because you can see in my work this certain level of heightened emotion when I first became a mom, and looking at those drawings that I made I’m portraying a lot of myself, exhausted. But then even as I shifted to the period of having two children, my work really took on this extreme, tight, controlled, realistic aspect while at the same time it had these very drastic, fast-moving, abstract marks. And it was really the only way I could think of to portray the paradoxical feelings of motherhood.

And it also was just a really deep, tumultuous time for me when we had our second child. So I remember working out with my father confessor that ultimately I think that my control issues were totally seeping into my drawings. We kind of figured that out together. And so it's just really interesting, that classic idea that your artwork kind of starts to talk back to you and reveal things to you about yourself.

JS: Sort of like a very personal, tailor-made examination of conscience.

LNW: Totally. And then things took another big shift when our third child was born. She is such a peaceful kid that I think ultimately there was a whole new level of groundedness that entered into my dynamic with my children. I think also, you know, obviously I'm maturing as a mom too and I’m maturing in my faith as well, everything’s obviously connected. But I think finally getting a kid that would sleep was huge. It just felt like, wow, I feel so much more settled now.

When our first was born, we had just moved back from living in Europe for two years. When our second was born, we had just become Orthodox. So everything was just all happening at once and it was pretty drastic and overwhelming, even though it was still filled with joy and happiness, you know, it was all mixed together.

JS: Yes, a lot shifting at once.

LNW: Right, but when Edith, our third, was born it just felt like, wow, we actually have our footing in our church community and my maternal heart feels more grounded. So my work kind of started becoming a bit quieter in the emotion and kind of heightened in, I don't fully know how to put it into words, but I have become more interested in the essence behind things rather than the dramatic emotion behind them. I kind of want to get at like a nostalgic sanctity within the mundane, if that makes sense? I really love how something so commonplace, as you and I have talked many times before, something so commonplace can be the contributing factor, like capital T, capital H, capital E—THE contributing factor to our sanctification and the way that the Lord is truly making those fine sculptural corrections on our hearts, you know, and he’s refining our heart not through these big movements anymore. There definitely are big movements in our lives, boulders that he’s crashing off of us, or big moments, but ultimately I feel like those are part of an earlier, more immature phase in your spiritual life. When that’s happening it’s like a parent saying, “Get this through your head!”

And then, then once you kind of break down those big boulders, the Lord doesn’t just stop working. He then gets to those nuanced aspects. And it’s really interesting to me that the nuanced moments happen in very simple moments in life. And these crucial moments, like for someone to learn patience or diligence, it is a much more crucial thing than to learn, I don’t know, courage, let’s say. You can have a courageous moment, like, boom, I felt courage and I went forward with it. But to learn diligence or patience, it takes a different type of essence, and I’m really interested in trying to play with that essence.

I don’t know. I’ve never shared that before, so I’m kind of processing out loud a little bit.

JS: No, I like that. And that’s actually a perfect segue to what I wanted to ask you next. We’ve talked about the way in which there was a shift in your newer pieces: Since your third child was born, they have a different approach. They have slowed down; those heightened emotions aren’t present; a kind of quietness has entered in. Sort of like you are honing in on these mundane but sacred, holy moments, and trying to unpack them or understand them. You also shifted back to painting, which you’ve shared with me that as a medium also reflects this slowing down as you try to zoom in on where the mundane and the holy kind of collide. Maybe “collide” is the wrong word as it’s so loud, but where those sacred and earthly moments sort of intermingle.

LNW: Yeah, there’s definitely an interesting study of material that started to emerge kind of unknowingly and subconsciously. I didn't start out working in charcoal and graphite thinking to myself that I wanted to specifically study the material. For those that don’t know my history, I painted for most of my life. Then when I had kids I stopped painting and focused on charcoal and drawing because I was nervous about the material around my first baby. I didn’t know how to manage that. At the same time, I had always wanted to strictly work in charcoal and graphite just for fun. So it was the perfect opportunity to do so. And then a few years into it, I became very interested with how the material itself was contributing to the scratchy emotions I was feeling. And so it kind of really worked out to be the perfect material to use as I was studying these very rough and non-stop emotions. On the one hand, I related it often to my skin feeling really soft after giving birth, but then the sandpaper that it can feel like when you’re nursing for the first time—that type of contradiction. Charcoal and graphite just really intrinsically portrayed that.

So then it was really interesting that within my own heart I kind of reached a more settled point, and the urge to paint came back at the same exact time, and it was exactly five years later. And the paint—painting material is slower, it is a slower process in itself. It kind of felt like this whole convergence. Like everything was pointing me in this direction.

And it was interesting that while the material and the phase of life kind of shifted and matured, my space didn’t change. Ultimately I was still in the same space, the same pool of water, if you will. I’m still swimming and I’m still going through the same motions, but my eyes were kind of opened up to many more moments of slowness and boredom.

Like we were talking about at the Wellspring Mother Artist Retreat last fall: it’s this hilarious boredom of just laying on the floor and not doing anything, and it can really feel like your mind is going to mush. I think unfortunately there are many cultural lies in your head as a mom saying that really you are doing nothing, when in reality there is so much more going on in that moment of you lying on the floor. And we’re missing it because our minds are caught up in some grander sense of… of what, really? What is more grand than being with your children and helping them develop in either their language or in their spatial awareness or in their, you know, schooling if you homeschool. And so since my children are all five years and younger, it’s these moments. Trying to find intrigue with their world, their material and, essentially, their pace of life.

JS: Your world was once their only world, that child-mother connection is so strong in that way. But now you’re beginning to enter their world. A separate space to discover and find wonder in.

LNW: Yes! And so that’s why many of my paintings now, I feel like there’s often a sweeping pattern in many of them because that’s a literal depiction of the rugs that I lay on. The light is a bit stronger, even though I’m attempting to paint it softer, I don’t want it to be aggressive light, but it still is very strong light. Ultimately I find that these moments in our day in which I’m letting myself slow down with my kids are also very dramatic. Like those moments when the sun is very dramatically streaming in through the window, casting shadows.

JS: Yes, definitely. I find that too, the way light enters in, it’s almost like a little reminder to stop and look. To stop and see the glory and beauty around us in these mundane moments.

LNW: Yes, and it’s interesting to me to try to capture these moments that we’ve actually all been in, which is, you know, moments of just laying there and watching the light shift on the wall. In these moments I have found that my mind so easily starts to wander and explore these very, very deep questions. You kind of can get a bit existential at the same time as being nostalgic, you know, at the same time as being kind of lazy or bored. It’s just this one simple moment holds all of these different emotions. So I don’t even know if that is answering your initial question.

JS: No, it is. I like that. In many ways it seems like what you’re describing is a kind of mirroring, or reflection of the story of Christianity and the story of Christ. The cosmic meeting the mundane. And it’s all intertwined in there. Because the God of the universe chose to enter the world in the way he did, it allows for these moments to have all these emotions, this significance, all of these things kind of coming together. The divine bursting into the earthly both sanctifies the ordinary and the mundane, but we’re also fully enmeshed in it, in the boredom, the frustration, the commonplaceness of it.

LNW: Yeah. That’s a really interesting thought, actually. I hadn’t specifically thought about that before, but you’re right. There’s this saying about the Theotokos of how she contained the uncontainable. God is uncontainable, he is beyond everything. But at the same time since he came, came into something so small, now his likeness is there, so deeply there. I mean, I know that his likeness was always there. But in this new way, it is kind of like he highlighted these simple things.

JS: When I first came across your work it was because I saw a photograph of you with a baby nestled on your chest while working on a large canvas. As I’ve learned more about your work and gotten to know you personally as a fellow artist, mother and friend, we’ve explored the ways your faith is an essential part of your process. I’m still searching for what this all looks like for me, to weave these parts of myself together. So I’m wondering if you could talk about how these aspects of yourself inform each other, intersect, conflict, dance?

LNW: I feel like before we became Orthodox, in all honesty, my prayer life pretty much was somewhat non-existent. Or, I mean, it existed, but I’ve always held onto a very personal dialogue with God, but it felt overly personal, the kind of personal where you’re actually disconnected from everybody. And so I was pretty much just inside myself, talking in my head to God, but ultimately in my own head. So I feel like when we became Orthodox, one major shift was how much I was drawn out of myself. How much Orthodoxy is about interconnection. You can’t really talk about one aspect of Orthodoxy without it naturally linking to something else. It’s a way of life.

Another major shift and aspect that I appreciated, which I know is also part of Catholicism, is the structure, the liturgical structure. You can have an outline for your entire day of prayer that you could follow. And the structure isn’t just rules for rules’ sake. It’s not like, okay, so now I need to say the saint prayer in front of this icon at this time and the blah blah blah. It’s not void of personal connection. It really exists as—like, I always think about it as bowling alley bumpers. You are going down the bowling alley, and you’re with your spouse, with your kids, with your father confessor, with your community, trying to figure out how to have your home be a “little church." And you’re really trying to integrate everything.

It’s obviously beautifully executed in the liturgy; you go on Sundays and it feels so worshipful and purposeful. And then you have to try and take all of that wonderfulness and integrate it into your home life, which feels chaotic and all over the place.

And I feel like, you know, simultaneously in the midst of what’s happening within the world, and with coming out of the pandemic and then simultaneously with my studio practice, it’s kind of been a process of me searching for how to integrate everything, really. Because I am not good at compartmentalizing. So my studio practice and my artistry has got to somehow meld in a fluid way with my mothering, which has to somehow meld in a fluid way with my prayer life, which then naturally connects with our church life as a whole, you know, and then which naturally needs to come back to my artistry because ultimately none of that is disconnected.

It’s all got to be intertwined because otherwise I actually can’t do it. It’s kind of funny when I hear people say things like, “Oh, I need to just have this space over here and that space over there and structured over here.” And I think, well then, how are you ever going to get to the studio? How are you carving out this time? I don’t understand. And then it’s really funny because then people look at my life, you know, on social media and they say, how are you getting so much done with all the kids? And I think that I finally have just realized that this is what works for me. This is what works for my children. And we’ve got to do it kind of all fumbling down as a giant ball of laundry down the stairs. We’ve got to all do it together. Which ultimately means probably I’ll be much slower. But I’m really okay with that slowness. At this point I can’t go any faster.