The Crucifix That Keeps On Coming Back

Postcard of the altar, tabernacle, candlesticks, and crucifix at Holy Cross Church around 1907, from the San José Diocesan Archives

This is a saga about the remarkable survival of a precious crucifix from Italy, a bittersweet story that is not quite over yet. The crucifix was first installed in 1907 at a little mission church that was built to serve the mostly Italian neighborhood of Northside San José, and it has survived multiple catastrophes since then.

The crucifix was thrown in the trash in the 1960s, rescued by a custodian, stored in pieces in a garage, and returned to the church decades later, to be reassembled, restored, and reinstalled in the church in 2005 in time for the start of centenary celebrations. Even then the travails of the crucifix were not over. In 2014, the church was gutted by fire.

The fire spread quickly through Holy Cross Church on Sunday November 16, 2014. Flames started shooting up from the roof at the front of the church just a few minutes after the church had emptied following the 1:00 p.m. Italian Mass, while the pastor, Father Firmo Mantovani, C.S., was still greeting parishioners on the sidewalk. Nobody knows the cause for sure, but the fire most probably started in the choir loft just after the Italian choir had left.

Holy Cross parish schedules Mass in Italian once a week because the parish was first created in 1906 as a mission to serve the many poor Italian immigrants who lived in the neighborhood. And it was staffed by Italian-speaking priests. In the beginning, of course, the Masses at the mission church were in Latin, but after the Second Vatican Council the Masses began to be offered in Italian, and in English.

Even though most of the younger generation Italian-Americans have moved away, many of the septagenarian, octagenarian--and some even-older--Italians who are still around attend the Italian Mass every week.

The parish evolved with the neighborhood’s changing demographics to serve Mexicans, Filipinos, and others from many varied national and economic backgrounds who own homes or rent in the area. When the mission was originally created, the valley where San José is cradled was called Santa Clara Valley. Now it is famous for the tech industry, the valley is better known as Silicon Valley. Some who work in the high-tech industry along with many lawyers and other professionals have also been attracted to the Northside by the number of well-kept, moderately priced Victorians and Craftsman-era bungalows and the chance to live in a mostly safe, pleasant neighborhood near the city’s downtown, but you don’t see the professionals at Holy Cross, except for the odd exceptions like me (I too worked in the computer industry between 1985 and 2011, as a technical writer). Now because of the changed demographics, the parish also offers Masses in Spanish too.

I know that choir loft where the fire probably started very well. A few years after I bought my little Victorian home and moved to the neighborhood and started attending Holy Cross in 2002, I joined the Italian choir--because I was an avid Italianophile at that time, because I was trying to improve my Italian after a one-semester course in Italian I had taken before my only trip to Italy for the 2000 Holy Year, and because I was also trying get to know my neighbors, especially those of the Italian-American persuasion.

So I clearly remember the tangle of extension cords lying around for the electrified instruments used by the Spanish and English choirs, and I remember the possibly electrically faulty old organ played by the Vietnamese organist for the Italian choir, which interestingly enough had another non-Italian, a Korean, as a director. I also remember the dusty shelves and old wooden file cabinets stacked and stuffed with no-longer-used music sheets left over from before the Second Vatican Council. My organist friends tell me most choir lofts are fire hazards. Insurers say choir lofts are often not kept clean. Dust is incendiary, and it combines with accumulated clutter and often sloppy electrical wiring to create an environment with high potential for disaster.

The day after the fire, the local and national news excitedly reported about the finding of a more-than-a-century old strikingly beautiful ten-foot tall crucifix largely undamaged in the water-soaked ruins of the gutted church. As interviews made clear, the remarkable survival of the cross was a relief to the pastor and the parishioners in the midst of their grief about the loss.

Most importantly the Blessed Sacrament, but also the holy chrism oils, some other statues and religious art pieces were also saved from the fire. The walls were still standing, and the stained glass windows had also been spared.

But the focus of the news stories and practically everyone’s amazement was mostly on the beautiful crucifix. Some pieces of burnt canvas from a painting in the half dome had actually fallen and draped themselves around the head of the corpus, the body of Christ. The fact that the crucifix survived with only superficial damage--even though the roof had collapsed and debris had rained down upon it--gave everyone hope that the pretty little neighborhood church would survive also, and rise again from its ashes.

As I mentioned at the start, the truth is that cross has remarkably survived much more than this latest calamity during the 110 years since it was first brought over from Italy in 1907. There was a span of almost forty years when the crucifix went missing, after it had been taken down and thrown out in pieces with the trash during a remodeling in the 1960s. As radio announcer Paul Harvey used to say, here’s the rest of the story.

1906

Let’s first go back and start at the beginning.

The first church building for the Italian mission that became the parish that was later called Holy Cross was dedicated on December 8, 1906 as Most Holy Crucifix, in Italian, according to the first entries in the parish record book. When its status changed from a mission to a parish in 1911, the name of the church and the parish became Most Precious Blood. The final change to the English name Holy Cross was made in 1927.

According to an article published in the archdiocesan newspaper The San Francisco Monitor on 9/11/1911, the first “neat little Italian church … was built in the memorable year of 1906.” The year was memorable, of course, because of the great San Francisco earthquake, which also did enormous damage even 45 miles away in San José.

The Monitor was the newspaper of the Archdiocese of San Francisco, and Holy Cross in San José was part of the San Francisco archdiocese at the time. (The new Diocese of San José that comprises Santa Clara County in the south bay was not established until 1981.)

A typewritten history of the parish written in the 1930s, which was found in the Diocese of San José’s archives, stated that the church was built for “the convenience of the Italians living in St. Patrick’s parish” by the St. Patrick’s pastor Father J. Lally.

St. Patrick Church San Jose after the 1906 Earthquake

Archbishop Montgomery, coadjutor of San Francisco Archbishop Riordan, formally blessed the new church on December 8, 1906.

Father Lally’s completion of the Italian mission church is especially praiseworthy considering that his own St. Patrick’s Church was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake in April, eight months before the new mission church’s dedication[i].

1907

The installation of the crucifix and new stations of the cross was notable enough to merit an item in the “Church News of the Week” section of The Monitor on 9/21/1907, which reported the erection of a large crucifix over the main altar on Sunday 9/17, and it lauded new stations of the cross as “beautiful oil paintings, imported from Italy.”

From The Monitor on 9/11/1911 captioned “Church of the Precious Blood (Italian), San José

1920

Detail from Window in the 1920s Church

A new, larger stucco church was built facing Jackson Street and dedicated in 1920 (during the pastorate of Father A. Bruno). The original church on the corner of Jackson and North 13th Street was not torn down at that time and was used for catechism classes and parish offices for many years. No one I talked to remembered what happened to the first church building. It may have been razed in the early 1970s after the parish purchased adjacent properties and removed several buildings to clear the way for a new convent and the present classrooms, which were dedicated as a CCD (Confraternity of Christian Doctrine) center on May 23, 1974.

Stucco Church Dedicated 1920 (photo taken in 1950s)

This is the 400-seat Italianate Basilica-style Holy Cross church building that was later gutted by the fire in 2014. After it was built, the crucifix from Italy was installed above the high altar, over a tabernacle and six brass candlesticks-- as you can see in the photo of a 1950 wedding.

Holy Cross Church Interior 1950 Nunes Wedding

1966

In 1966, then-pastor Father Joséph Bolzon C.S. installed a new altar that could be walked around so the priest could celebrate the Mass while facing the congregation. In stunning disregard for the artistic not-to-mention sentimental and financial value of the items, the crucifix was thrown away along with a marble scaled-down copy of Michelangelo’s Pieta and the fourteen painted stations of the cross. The high altar and the altar rails were also discarded.

Soledad Vallejo, who was the church caretaker at the time of the remodeling, took pity and rescued the crucifix, stations, and statues. She kept the Pieta in her family’s living room and stored the stations of the cross and the broken pieces of the crucifix in the garage of her house. Vallejo dreamed of building a small chapel in the Philippines to house everything, but eventually gave up the dream because the logistics would have been too hard to manage.

Wedding after 1966 Remodeling (Notice the Change in Clothing Styles Also)

The only crucifix used after the remodeling was a much-smaller one that topped a new modern-style gold tabernacle. The tabernacle was placed on a table behind the altar in front of a framed image with a gold-etched depiction of the Last Supper against a black background. Later, light marble walls with streaks of beige were installed behind the altar part way up the walls of the half dome.

1970s

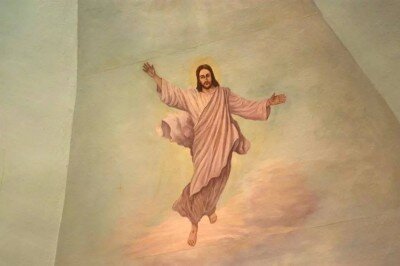

A mural by a locally well-known self-taught Italian American artist, Anthony Quartuccio, was commissioned for the half dome in 1977. (The bottom of the mural is visible in the baptism photo that was taken. The top is in the close-up photo.)

Quartuccio, whose day job was delivering mail at NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, painted Jesus resurrected and hovering above three empty crosses at the top of a center hill. In the painting, the hill was part of a range that deliberately resembled the Diablo mountain range--which residents of the neighborhood see every day as it runs along the east side of the Santa Clara Valley.

Quartuccio’s daughter recalled in one article seeing him painting the panels of the mural in the family kitchen when she was a teenager. Quartuccio was quoted in another article as saying he painted the mural on canvas because he didn’t have the skills for fresco painting. After he finished the panels, his crew hung them in the half dome.

Mid-1970s

A subsequent pastor, Father Mario Rauzi, did another renovation that removed the black framed piece some time in the 1970s.

Half Dome and Altar after 1970s Remodeling

The tabernacle was moved to a small altar to the left of the main altar. A new plain crucifix was hung on the center marble panel. Somewhere along the years, the ornamental designs around the half dome were painted over in neutral beige.

2000s

Soledad Vallejo, the caretaker who saved the crucifix in her garage, died in the 2000s. Her daughter, who by that time had moved away, first thought she would donate the crucifix and the stations to her church in Fresno. Once again, logistics played a role in the fate of the crucifix. Difficulties she would face in transporting the crucifix from where she was cleaning out her mother’s house in San José to Fresno led her to contact Brother Charles Muscat, C.S., the Director of Religious Education, to ask if Holy Cross would want the crucifix back.

Soledad’s son took the Pieta; the daughter kept the stations; and Holy Cross took back the crucifix. Brother Charles’s brother, Grezio Muscat, put the pieces back together while visiting from Canada for a month, and the brothers hung the patched-together crucifix in one of the classrooms. Brother Charles also kept the original tabernacle, which may have been also returned by Soledad Vallejo’s daughter.

2005

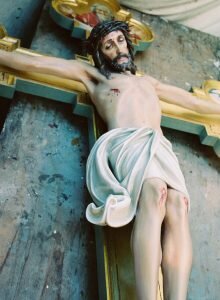

As the 100th anniversary approached, then-pastor Father Clair Orso, C.S., commissioned David Dittmann, a Santa Clara art restoration expert, to restore the crucifix, which as it turned out is an irreplaceable piece of art. Dittmann told me at the time that the crucifix was crafted of close-grained, knot-free joined wood that was skillfully aged beforehand to prevent shrinkage, a quality of wood that would be impossible to get today.

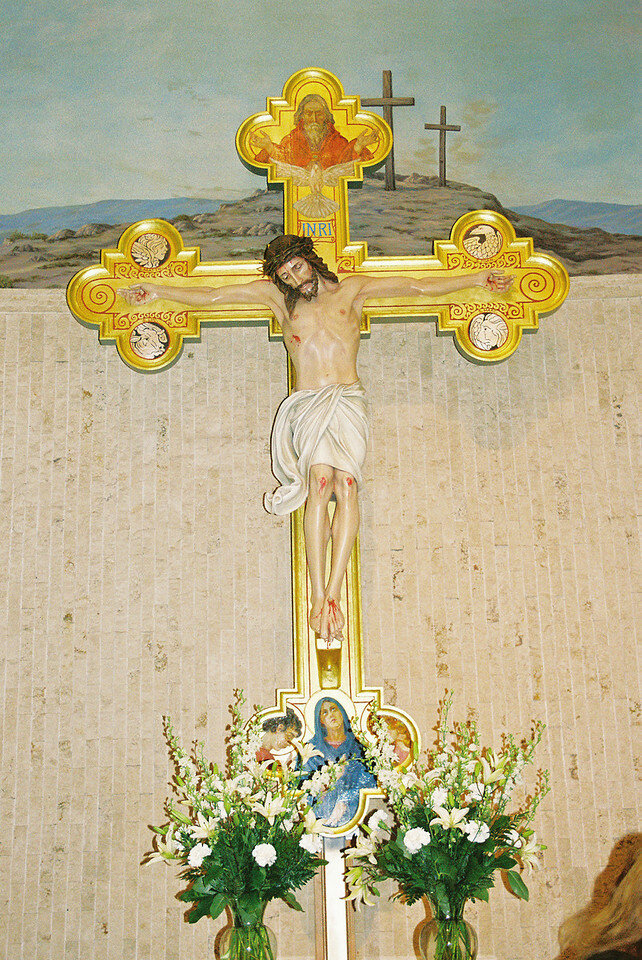

A small painting of God the Father and God the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove is at the head of the cross, and another small painting of Our Lady with John the Evangelist and Mary Magdalen is at the foot. The arms have silvered representations of the symbols of the four Gospel writers, the lion, the eagle, the ox, and the man.

Dittmann reapplied 23 carat gold leaf on the front of the cross, resilvered the symbols of the Gospel writers, and repainted the corpus and the small pictures on the cross.

Dittmann’s work was completed in time for unveiling on the Feast of the Triumph of the Holy Cross on September 14, 2005, which the parish chose as the starting date for its 100th anniversary celebration. The anniversary celebration continued for a year and concluded on December 10, 2006, almost exactly 100 years after the first church building for the parish was blessed on December 8, 1906. A group of the Dittmanns’ friends and neighbors helped move the crucifix to the church, but not before the Dittmanns’ Goddaughter bent over in sympathy to kiss the owie on Jesus’s scraped knee!

These two couples were married in front of this crucifix before it was removed in the 1960s

At Holy Cross, the crucifix was welcomed back by a group of long-time Italian members of the church, who helped bring it into the CCD building and then into the church to mount it. On the Feast of the Triumph of the Holy Cross, the rescued crucifix was unveiled after almost forty years absence. Some remarked on the significance of the Biblical forty years. Regina Dittmann, David Dittmann's wife, commented at the time that “The Triumph of the Holy Cross is the Resurrection. And the triumph of this little cross is its resurrection.”

I wrote two enthusiastic articles here and here for the Valley Catholic diocesan newspaper about the centennial and the restoration of the crucifix. At the time the return of the crucifix seemed to me to be a triumph, as it was for many others. But then after a few years I began to think about what bothered me about the crucifix’s return. The broken crucifix had been patched together, beautifully polished, repainted, resilvered, and regilded, but when it was put back into the sanctuary, the beautiful things that had formerly surrounded it were gone and the harmony of the former interior was replaced with a kind of visual dissonance.

As we can see from the 1950s wedding photo, the crucifix originally hung from a half dome over a shelf altar with six large impressive candlesticks and an ornate tabernacle. The impression given after the restored crucifix was replaced 2005 was quite different. The half dome was still there, but the top of the half dome had in the meantime been covered by the Resurrection mural. The cross was mounted on a pole behind a new smaller altar that can be walked around. The crucifix listed a bit to the left, and obscured part of the dome painting. It was flanked a bit incongruously by two small oak tables for holding flower arrangements.

When I looked at photos of the church before the remodeling, the crucifix had seemed fitting in its place as a focal point over the altar, when the Mass would be celebrated with both the priest and the people facing towards liturgical east during Mass. After all the changes, the focus on the altar had dissipated and the crucifix seemed out of place.

Of course, many conflicting expectations, requirements, and factors such as finances have to be juggled when any church building or remodeling project is started, and no matter how well-intentioned and knowledgeable one is, one cannot always get what one wants.

For one example from the Holy Cross saga, Fr. Claire Orso, C.S., then-pastor in 2005 told me that the diocesan environment committee would not approve the rehanging of the cross from the dome and the replacement of the old tabernacle in the center where it used to be, unless he would agree to remove the few remaining statues that had survived successive remodelings and to remove the side altars to meet with new guidelines that require only one altar per church. He wouldn’t agree to the conditions.

2017

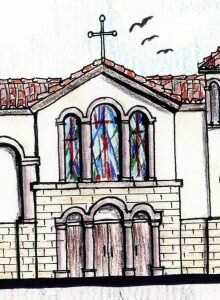

Soon after Holy Cross Church burned down, I read that the firemen had pronounced the walls sound, so I hoped they could be saved. I also harbored the hope that by some miracle the church would also be restored to how it looked in the 1950s photo. Those hopes were dashed when I interviewed the latest pastor a few weeks ago, Fr. Livio Stella, C.S. The walls had to be demolished because they contained asbestos, and so the church was torn down and is in the process of being rebuilt from the ground up. Fr. Stella showed me the architect’s renderings of how the church will look when it is rebuilt. The new pastor also told me a bit about the trade-offs he had to make while negotiating the design for the new church.

A praiseworthy goal for the new design was to keep the original Italianate basilica style of the church as far as possible. Most of the churches in Santa Clara Valley have been built or remodeled (or as some of us say, remuddled) to accommodate worship in the round. So being able to retain the basilica style at Holy Cross with the pews facing the same direction was a big win. One other piece of good news is that the stained glass windows that were saved will be installed in the new building. But many of the other features of the planned church are a disappointment, at least to me.

Some good news is that an organ is being built by the same company that made the previous organ that was destroyed in the fire.

But oddly enough, the choir won’t be able to sing in the loft with the organ, because building regulations would require the church to put in a prohibitively expense elevator for handicapped accessibility to the choir loft. The choir will sing at the front of the church to the left of the altar near a minimalist baptismal font in a minimalist sanctuary. (Scholar-friends from the Church Music Association of America and many other experts in liturgical music say a choir should support congregational singing and that a choir should never sing at the front of a Catholic church.) A wireless keyboard played by an organist near the choir downstairs will control the new organ. I’m not an organist, but I can’t imagine that playing a moveable keyboard will give anywhere near the same results as playing at a traditional organ console.

More bad news is that replacing the half dome would be too costly.

The church lost three rows of pews in the back because of requirements from the city and ADA for the addition of handicapped accessible bathrooms, which take up extra space. There will be only one altar, which looks in the renderings to be a plain grey rectangle, and a similarly sparse looking gray ambo and a baptismal font will be on the left. The old tabernacle will be placed in a grey stone wall behind the altar, but the renderings do not show details how that will be placed.

On the outside, the new church building will resemble the old, minus the dome. It will no longer be elevated up a flight of steps. People will be able to walk or roll right in from the sidewalk, into a high-ceilinged lobby hung with a glass chandelier such as one might see in a hotel or office lobby. The old church had a tower in the back, while the new church’s tower will now be in the front, which, according to Father Stella, makes its design more consistent with California architecture. A rustic mural of a crucifix that used to be in the center top of the facade was another feature saved from the fire; it will be placed in an arch to the right of the front doors. The Mass times will be listed in another arch to the left of the doors.

Planned outside front of the new Holy Cross

There will be lots of windows in the new church, both the old stained glass ones and others admitting natural light. There will be frosted windows on the facade that faces the street, and more clear or frosted windows (I can't tell which) on the back of the church. The nave will be flanked by two rows of clerestory windows that appear in the plans to be plain glass and whose opening will be adjustable according to the weather. The light from the windows in the back wall will light the sacristy and will shine through the art glass in the sanctuary. The purpose, Father Stella told me, is to bring more light into the church. This will “make it more for the people,” Father Stella told me, "since Pope Francis said that all churches should be for the people and if they are not for the people they are no good."

Does that imply, I wondered to myself, that churches for eons were built without clear glass windows were somehow not for the people? But I digress.

And what will be the fate of the venerable crucifix? It will hang above the same stone wall where the tabernacle will be placed, against a curved background of non-figurative blue-green art glass blocks, again as one might find in a hotel or office lobby.

I have a degree in Studio Arts and have studied architecture in Art History classes, and to my eye, the termination of the clerstory windows at the sanctuary wall are a jagged interruption. Instead of an arch or an uninterupted rectangular space above an impressive altar with perhaps a canopy or baldacchino to properly focus our attention on the Altar of Sacrifice, we will see non-traditional ceiling shapes and beams that call to mind an auditorium, a curved wall of blue-green glass, and a stone wall. The comparatively tiny undecorated marble altar and ambo are visually insignificant in that unfocused space.

The architect Ramon Torres wrote at his company's website (TOPA Architects) that he is not an artist (as you can see the proof from his initial sketches for the design of the new Holy Cross below). This may be common that architects can't draw, but I was surprised he didn't painstakingly draw his plans out for the customer; his rough renderings seem as though they are computer generated with a kind of hodge-podge of selections from various catalogs, and they leave me guessing about how the church will look when finished. Color and consistent design are highly important in the design of any interior, and it's hard to tell what the colors and final design will look like. The pews, for example, will be a different style and color and size than shown in the photo of the wall of art glass and the crucifix, and the flooring will be a different color than is shown. But who knows what they are going to be?

Contrast the architect's sketches and renderings for Holy Cross Church with these beautiful renderings of the design for Christ Chapel, Hillsdale, Michigan by classical architect Duncan Stroik.

Sad to say, it seems to me unlikely that all the pieces shown in the renderings will come together to make up one visually harmonious whole. I fear that the old stained glass windows, the beautiful old tabernacle, and that long-suffering crucifix may be the only things of classic transcendent beauty we will see in the new church when it is completed.

These photos are keyed to a list of items with prices that parishioners are asked to choose among to donate. "Make a piece of the New Church of Holy Cross your very own." For example, if you pick item #4, you can adopt one of the 75 units of blue-green art glass behind the altar for $2,400. For $15,000 you can adopt the moveable organ keyboard, shown as item #12, or for $10,000 you can adopt the altar in #16.

There is much more that can and should be said about the forces at play in the way that churches like Holy Cross are designed now, and what might have been done to work around the obstacles. I am seeing that a lot is being written these days about a return to classic architectural principles for both secular and church buildings and there is a gradual turning away from the modernist Bauhaus-influenced and Protestant-influenced style of "church as meeting hall" to a return to the ideal of "church as sacred space," as "domus Dei," house of God. Church architects and the priests that are their patrons need first of all to understand the language of sacred architecture before any plans are made.

[I]t is an antinomial view, derived from the Enlightenment, which claims that a church cannot be both God's house and the house of His people, who are members of His body. When the church is thought of merely as house of the people of God, it becomes designed as a horizontal living room or an auditorium. These two historic names, domus Dei and domus ecclesia, express two distinct but complimentary natures of the church building as the presence of God, and the community called together by God. 'These visible churches are not simply gathering places but signify and make visible the Church living in this place, the dwelling of God with men reconciled and united in Christ.' (The Catechism of the Catholic Church)"--Duncan Stroik in "10 Myths of Contemporary Church Architecture"

For one example of this trend, architect Duncan Stroik has published a beautifully illustrated book The Church Building as a Sacred Place: Beauty, Transcendence, and the Eternal that I have received to review from the publishers. Some say this book should be on the table of every church-building committee and read by every pastor planning to build or remodel. If you can't wait for my review :-), you can read where many of Stroik's ideas from that book are summarized at his firm's website (10 Myths of Contemporary Church Architecture).

Finding money for traditional church features such as the half dome that was in the burned Holy Cross church is a well-known problem. But some say that classically beautiful masonry church buildings can be built for the same amount of money as modernist churches that are sparsely decorated. And others say that even when classically beautiful and inspiring designs and materials turn out to more expensive than alternatives, when the uplifting designs are put before Catholics, the extra money often gets generously donated in response to the beauty of the designs. But these are topics for another essay on another day.