Reading Crime and Punishment with Dorothy Day

In 1972, William Miller was writing a biography of Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement. When Day heard the title he had proposed for the book, she felt compelled to write him a letter; “I am so tired of that quotation being used and ascribed to me rather than to Dostoevsky.”

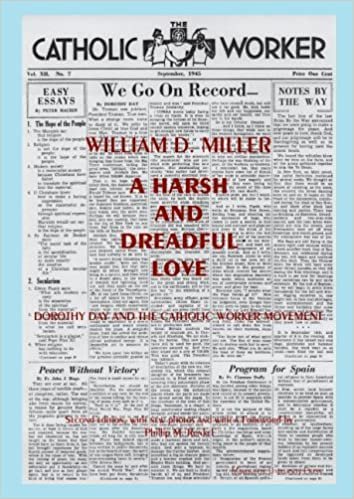

Despite Day’s frustration, Miller’s biography, A Harsh and Dreadful Love, was published with the proposed title, which referenced Fr. Zosima’s words in The Brothers Karamazov; “Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing compared with love in dreams.”

One can imagine a worse fate than having a great author’s words ascribed to oneself. Still, this misattribution had become a sore point for Day. Though she loved Russian literature, she was dismayed that her habit of quoting Tolstoy and Dostoevsky caused some people to think the latter’s words were her own. In fact, Russian literature was so formative for Day that Stanley Visnewski, a long-time Catholic Worker, said, “the only way [one] would ever understand the Catholic Worker was by reading Dostoevsky.”

I’ve been reading Dorothy Day’s writings for the better part of fifteen years now; in fact one might go so far as to say, “the only way to understand the Baker household is by reading Dorothy Day.” During that same period, I’ve been slowly trying to read some of the great works of Russian literature. Despite Day’s recommendation, I dragged my feet until a little book-club style peer pressure convinced me to give Crime and Punishment a chance.

After spending roughly six hundred and fifty pages staggering under the weight of Raskolnikov’s guilt and self-doubt, suddenly, in the second chapter of the epilogue, Visnewski’s comment - “the only way to understand the Catholic Worker” - struck me in a whole new way.

I think it’s fairly obvious that Day could relate to the challenges which Dostoevsky’s characters face. One diary entry lists some of the suffering surrounding her; “Unrequited love, forbidden love (the young), epilepsy, brain tumor, emphysema, drink, madness, old age, youthful delinquency, the suffering little children.” Day’s list of companions reads like a catalog of characters in a Dostoevsky novel, but Crime and Punishment offers something more than a mirror reflecting the difficulties of life: it offers a very specific variety of hope that must have been of great interest and comfort to Dorothy Day. This hope is embodied in the relationship between Sonya and Raskolnikov.

Sofya Semyonova, or Sonya, is an impoverished teenager, a believing Christian who has turned to prostitution to support her family. Sonya befriends Raskolnikov, the murderer guilty of the book’s titular crime. Despite being afraid of his irascible and unpredictable nature, Sonya demonstrates a timid yet imperturbable patience with Raskolnikov. She follows him to prison in Siberia, where despite his daily rejection of her kindness, she continues to visit and care for him. For a year she perseveres in patience, until finally, after illnesses which cause them to be separated for a time, Raskolnikov realizes how much he cares for Sonya. When they are reunited, he falls at her feet in tears and Sonya’s patience is rewarded with Raskolnikov’s long-awaited conversion.

To Day’s mind, Raskolnikov, just like the strangers who showed up at the Catholic Worker, was Christ, the “poor lost ones, the abandoned ones, the sick, the crazed and the solitary human beings whom Christ so loved and in whom I see, with a terrible anguish, the body of his death.” Sonya’s constancy in waiting for the “other” exemplifies the way Day hoped she and her fellow Catholic Workers would treat their guests, and indeed all those who crossed their paths.

Unfortunately, as Day repeatedly laments, the patience and hospitality which proved life-changing for Raskolnikov are often not what the poor encounter in their need. In her diary, she writes of, “the bitterness with which people regard the poor and down-and-out. Drink, profligate living, laziness, everything is suspected. They help them once, the man who comes to the door, but they come back!” Day recognized the poor as, “‘our least brethren,’ in whom we may see Christ,” no matter how frustrating the interactions might be. It was the work of the Christian, therefore, to welcome the poor for Christ’s sake.

Yet even when Day was able to offer this love and patience, it sometimes wasn’t enough—people did not make it to the end that Day would have liked for them. Their pain, their addiction, their illness, proved too much for them to overcome in this life. In 1954 she mourned the murders of Max and Ruth Bodenheim, long-time friends who had stayed at Maryfarm and Peter Maurin Farm. “How little we were able to do for Max or Ruth. The bare bones of hospitality we gave them.” But even in that sense of failure, Day holds out hope; “...[God] has after all done it all, repaired the damage, died on the Cross for us, wiped away our sins—Ruth’s sins, Max’s sins, and in some miraculous, beautiful, glorious way, opened up for them the gates of eternal life. I see this thru a glass, darkly.”

Alcohol, misplaced sensuality, and poverty had been the suffering and finally led to the death of Dorothy’s friends. It was indeed “harsh and dreadful” to watch people whom she held close to her heart suffer, and thus it is only natural that she reacted so strongly to the pages of Dostoevsky. In fact, she wrote in her column that, “I do not think I could have carried on with a loving heart all these years without Dostoevsky’s understanding of poverty, suffering, and drunkenness.”

Dorothy Day spent her life in a Dostoevskian world, surrounded by the terrible fallenness of humanity. Crime and Punishment plumbs the depths of sin and suffering, but offers a ray of hope at the end. Its story is as dark as that of any addict who came to the Catholic Worker seeking a bed, and yet recognizes that even in the clutch of great sin, each person is still a child of God, and still deserves to be loved as an alter Christus. Just as Sonya never gives up on Raskolnikov, Day believed “We must learn to love people ‘in their sin,’ as Dostoevsky says.”

Crime and Punishment would seem to have yet another attraction for Day - it suggests that one need not be a saint to be a witness of faith to a sinner. Why should Dostoyevsky choose a young, often fainthearted prostitute to trigger the conversion of an unrepentant murderer, while his good and generous friend and his virtuous and caring sister are entirely unable to reach him? In this way, Sonya is again a model for the Catholic Worker, and one to whom Day herself, with her colorful Greenwich Village past, could relate. No one is perfect, as the frequent squabbles over leadership and methodology in the Catholic Worker attest. Throughout her life, Day was acutely aware of her own faults, among them a quick tongue, a hot temper, and impatience. If a prostitute (though admittedly a reluctant one) like Sonya could read the Gospels to and open the eyes of a murderer, there was a chance that any of the sinful, hopeful people who worked with Day could figure in similar conversions.

It wasn’t their own efforts, after all, which caused the change, but the Spirit working through them. Sonya represents the hope that despite one’s personal shortcomings -whether sinfulness, quirks of temperament, or other human foibles - patience and the gift of one’s own presence could lead a lost soul to Christ.

As much as Dorothy Day might have recognized in Sonya the epitome of the Catholic Worker, she undoubtedly also saw in her an example of how any Christian who took the Church and the Gospels seriously ought to act. It is the writings of one of Day’s favorite saints, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, which brings it all together. Sonya could be seen as practicing the “Little Way,” the art of making a gift to God of every little task and sacrifice. “The message of Thérèse was too obviously meant for each one of us, confronting us with daily duties, simple and small, but constant.” Dorothy recognized that this call applied not only to herself, but to her fellow Catholic Workers as well. Furthermore, Day believed that just as all those in need deserve to receive the care one would offer to Christ, anyone who intends to follow the Gospel is called to give such care. Indeed, in her view all Christians are called to be alter-Sonyas, whether that means visiting those in prison, working the breadlines, or caring for an elderly neighbor.

However little Dorothy Day felt she had given, there was always the hope that, with God’s help, it would be enough—that her love might bring someone to God as Sonya’s love had. In the face of despair, the beginning of Raskolnikov’s conversion (which comes only in the short last chapter) must have been, for Day, a powerful reminder of the hope which animated her work.

Dorothy Day knew that all she could do was “lay the bricks” - that it was not for her to see the finished cathedral. “We might as well give up our great desires, at least our hopes of doing great things toward achieving them, right at the beginning. In a way it is like that paradox of the gospel, of giving up one’s life in order to save it.” Yet there is always a desire to see some small fruit of our labor, and Day was no exception.

Despite often feeling inadequate, Day lived in hope, and she rejoiced when she was granted a glimpse of how her efforts cooperated with God’s mercy, as in the case of Ammon Hennacy. Hennacy had long worked alongside Day, as their personalist and pacifist views coincided, and he frequently wrote columns for the Catholic Worker paper. Yet he had always been skeptical of Day’s commitment to the Catholic Church, and she had accepted early in their relationship that there was nothing she herself could do to persuade him of the truth of her faith. Sixteen years after their first meeting, Hennacy was baptized into the Church, and Day gushed, “What to say about such a conversion as Ammon’s, and how happy it has made us!” Here were her patient hopes fulfilled, as Sonya’s hopes for Raskolnikov had been, and as Dostoyevsky promises in the same passage quoted earlier from The Brothers Karamazov; “...just when you see with horror that in spite of all your efforts you are getting further from your goal instead of nearer to it—at that very moment I predict that you will reach it and behold clearly the miraculous power of the Lord who has been all the time loving and mysteriously guiding you.”

Day put her trust in this miraculous power and, like Sonya, focused on the mundane tasks within her reach while she waited in hope for the Lord to do his work. She knew she shouldn’t expect the consolation of seeing a conversion like Raskolnikov’s, but when the hoped-for happened, she hastened to praise God for his goodness.

I take Dorothy Day at her word when she writes to Thomas Merton that “Dostoevsky is spiritual reading for me.” Dostoevsky’s world is both peopled with sinners and illuminated by grace, a grace which often comes, as the Spirit is wont to do, from unexpected places. Day must have found that Sonya, in her willingness to “do what comes to hand,” in her stubborn desire for the salvation of sinners, and above all in her patience, epitomized the life of the ideal Catholic Worker. Indeed, for Day, Sonya may have represented the model Christian who, while clinging to the hope of God’s mercy, pours herself out for the sake of Christ in the poor.