Friday Links

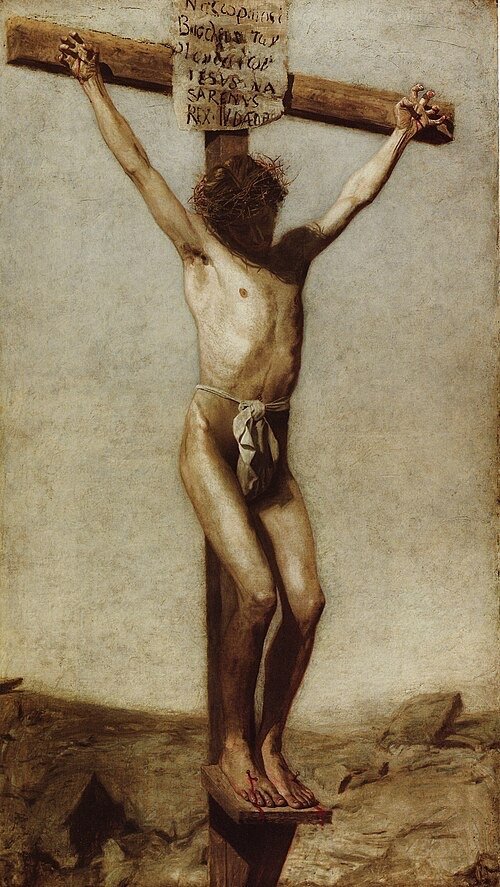

The Crucifixion by Thomas Eakins

The Miracle That Grew From the Ashes of 2018

Rhonda Ortiz on The Coming Home Network

Easter Bouquest of Poems 2025

Jordan Castro on “Living in Gatsby’s world We’re still fixated on self-creation”

Ethan McGuire: The Rusty Paperweight: April ’25

The Crucifixion by Thomas Eakins

The painting that accompanies today’s Friday Links hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, part of its permanent collection. Every time I go to the PMA, I am compelled to visit Eakins’s rendering of Christ’s last hours. This is the only religious painting the agnostic Eakins painted and, interestingly, it garnered quite a bit of controversy in its day: for its harsh, unrelenting realism (note the clawed fingers and the blood pooled in his legs and feet), its lack of halo, the lightness of the scene, the missing flank wound. But, as Elizabeth Milroy explains in her fascinating reassessment of this painting:

. . . the wound was mandatory in Crucifixion iconography. By omitting the side wound, Eakins locked the image into a specific instant of narrative time. At the ninth hour, Christ called out to God; he then surrendered his spirit; his head fell forward and he died. Because the Sanhedrin requested that the bodies of the crucified not be left on Golgotha during the Sabbath, the Roman executioners were ordered to break the legs of Christ and the two thieves with whom he was executed to hasten their deaths. When the soldiers approached Christ, they saw that he was already dead and did not break his legs: “But one of the soldiers with a spear pierced his side and forthwith came there out blood and water” (John 19:34).

Only the Gospel of Saint John describes the transfixion. And this Gospel also omits any reference to the darkening sky. In fact, Eakins’s painting corresponds exactly with the image evoked in John 19:30: “When Jesus therefore had received the vinegar, he said, It is finished [‘Consummatum est . . ‘]: and he bowed his head, and gave up the ghost.” For a literal reader of this Gospel, the moment of the “consummatum” was the most powerful instant in Christ’s Passion.

Milroy ends by calling this painting “a discomfiting curiosity.” I think it’s more than a curiosity myself, but Milroy makes some really compelling points about all art, not just visual art. When I view this painting, I find its depiction of the physical suffering of Christ incredibly moving and shocking because it is so easy to forget that he actually felt intense, agonizing pain. His hands and feet really did have nails hammered into them; his body really did hang on that cross for three hours; he really did feel thirsty. Eakins conveys all of that, but he seems to have missed something else, something essential and mysterious. Still…

The Miracle That Grew From the Ashes of 2018

Kevin Wells tells the beautiful, heartwrenching story of Fr. John Hollowell, his request to becoming a suffering soul for the victims of clergy abuse, and his miraculous healing at Lourdes. Today is a good day to read this extraordinary story. And, it’s good, as well, to remember that suffering—even the smallest, nothing-but-a-papercut type of suffering—can be redemptive. By offering up our own sufferings, we can join those, like Fr. Hollowell and the victims of clergy abuse, who live in agony, and by doing so, we can even help to console them. May God send us more priests like Fr. Hollowell, true shepherds, who care for their flocks.

I know of no one—on this earth—who responded to the Catholic Church’s 2018 Summer of Shame more directly, more bravely, or more strikingly than the priest raised in the quiet countryside of Indiana. When the Molotov cocktail of McCarrick’s secret life and landslide of Church sin exploded that summer, Fr. Hollowell descended a long, spiral staircase into the wilderness of the suicidal, the homeless, the meth addicts, the male prostitutes, the anxious, the alcoholics, the porn-addicted. He went to the valley of the ruined—the place of the victims of clergy sexual abuse. And he loved them there.

Rhonda Ortiz on The Coming Home Network

Rhonda Ortiz, Dappled Things Editor-in-Chief, recently appeared on The Coming Home Network to share her story of conversion from Evangelical Protestantism to Catholicism. It’s so good. I urge to listen to it and to share it with friends and family, especially those who are struggling. Rhonda is truly a gem.

Easter Bouquest of Poems 2025

Alex Rettie has put together a lovely bunch of poems here for the next three days, including Sally Thomas’s “Holy Saturday.” This is a nice companion to your spiritual reading over the weekend. And here’s a bonus from Plough, “The Eye” by Christian Wiman. It’s not a Triduum poem, except in the way all good poems are Triduum poems. Here’s another: Carla Galdo’s “Easter Triduum.”

Jordan Castro on “Living in Gatsby’s world We’re still fixated on self-creation”

Gatsby lives on in the American consciousness in precisely this way: it is a high-school novel; a novel one is forced to read at a time in one’s life when one cares more about literally everything in the world other than classwork; and a novel one remembers very little of. It’s a novel about the terror of nostalgic longing, and the American Dream — the romantic delusion that you can become whoever you want, through sheer force of will — but it masks itself in our collective memory as a high-school meme.

Ethan McGuire: The Rusty Paperweight: April ’25

Each month, the excellent New Verse Review posts their monthly round up. It’s always filled with good things (articles, essays, podcasts, poems) that I’ve read or meant to read, plus a few that are new. This month the list was compiled by the very fine poet, Ethan McGuire. He includes one of my new favorite poems, Matthew Buckley Smith’s “Egg and Dart.” I’ve been reading this poem (along with the Wiman poem from Plough) over and over for more than a month now.

Thanks also to Ethan for posting about The Living Fire Series: Contemporary Catholic Writers in the Classroom, edited by friends and DT contributors, Sarah Cortez and Lesley Clinton, forthcoming from Wiseblood Books. Catholic high school teachers, homeschoolers, and those who just want to learn more about what poetry will find these study guides to be a huge help.