How the West Chester University Poetry Conference saved American verse

This article, written by Matthew Kirby, was originally published in the October 2024 edition of The Local Fold, a print magazine of, for and by the lay faithful of West Chester, Pennsylvania, and its surroundings. For more information, visit thelocalfold.com.

West Chester University. Photo by Katie van Schaijik.

If there is a literary analogue for the way divine providence orders history, a likely candidate would be the terza rima of Dante’s Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, in which the unrhymed verse of one tercet provides the rhyme that bookends the following one. Out of place and alone, the odd line hangs awkwardly for a melancholy moment before bouncing back as the ordering principle of what follows.

Take, for example, the way the obscure poet and polymath Weldon Kees, who disappeared in 1955, brought Dana Gioia and Michael Peich together a quarter of a century later, when both men discovered a love for Kees’ work (he had been a kind of missing link between the midcentury formalists and the Beat Poets) and were brought together by a rare-bookseller in Nebraska from whom they purchased Kees’ titles.

Kees was like that unrhymed middle line in a terza rima stanza. He literally vanished, as if into thin air. Ominously, only his car was found parked near the Golden Gate Bridge. But the friendship he posthumously sparked between Gioia and Peich would lead them to revitalize formal poetry in the 21st century.

And they did it in West Chester.

The West Chester University Poetry Conference, first held in 1995, was for nearly 20 years the country’s largest summer poetry conference. But that superlative doesn’t begin to account for it. A good description of the event was written by poet April Lindner in an essay commemorating the conference’s 10th year:

“Wherever poets gather, one might expect to find passion about poetry—its pleasures and its value in a well-lived life—and one generally does. But the quality of the passion at the West Chester Poetry Conference is different, more intense, fueled by a desire to save poetry from obscurity and mediocrity.”1

The tools employed in this rescue mission were threefold: rhyme, meter and narrative. All three were conspicuously absent from much of the poetry being published in literary journals in 1981, when Peich and Gioia met.

The reasons why rhyme, meter and narrative largely disappeared from American poetry at the beginning of the 20th century are complex and varied (for anyone interested in that fascinating story, Timothy Steele’s Missing Measures is an engaging and informative read.) Rhyme and meter enjoyed a brief resurgence in the mid 20th century, but by the 1970s were deemed retrograde, incapable of conveying the spontaneity of real life. The result was that most poetry relied on tangled syntax, obscure or absurd subject matter, and typographical anomalies to differentiate itself from prose. Some poets, through ingenuity, genius or sheer will, managed to express themselves fluently or at least strikingly in this manner. But they were vastly outnumbered by bloated imitations. Worse, without the disciplines of rhyme, regular meter, and the tradition of English prosody, there was nothing that could be passed from one generation of poets to the next beyond the will to create. Aspiring poets found themselves alone in a trackless waste.

And that’s where West Chester, as devotees call the conference, made all the difference.

Richard Wilbur (left) and Michael Peich (center) with the president of West Chester University during the conference. Photo courtesy of Michael Peich.

The guild model: Teaching craft

“We didn’t teach creative writing,” Dana Gioia told The Local Fold. “We taught verse craft. I don’t think you can teach creativity but I do think you can teach craft.”

Craft was the backbone of the conference. Its various aspects were conveyed in workshops held on West Chester University’s campus: Sonnet, Experimental Forms, French Forms, Blank Verse, Dramatic Monologue, Poetic Line, The Lyric Poem. There were also practical classes like Putting Together Your First Book as well as critical seminars like The Historical Poem and Women Formalists.

These courses were taught by poets and scholars handpicked by Gioia and Peich. All were American masters of formal verse: poets such as Timothy Steele, A.E. Stallings, David Mason, Mary Jo Salter, Mark Jarman, and Rhina Espaillat. Each conference was anchored by an eminent keynoter. The first was renowned midcentury formalist Richard Wilbur. He was followed by Donald Justice, Marilyn Nelson, and other poets who had swam against the current before the advent of the new formalism (more on that literary movement later).

The conference was a place where poets could go to work out the thorny business of making poems with fellow practitioners. “If you’re pursuing an art,” Gioia told The Fold, “—let’s say the craft of shoemaking—you come to a point where you say, I don’t know how to make a high heel that doesn’t break off, I don’t know how to get this color, and so you go to other craftsmen and learn from them. What we were trying to do was to create a place where people who were called to be poets and were trying to work in poetry as (Robert) Frost would have understood it could get some of the necessary technical background.”

This exchange of long pent-up poetic knowledge spilled over beyond the workshops on campus onto the undulating brick sidewalks of West Chester, sports bars where the poets rubbed elbows with Phillies-hatted locals, and the Peichs’ home, lushly surrounded by Mike’s wife, Dianne’s, elegant gardens.

“We were a democratic group,” Peich recalls. “There was no pecking order. Everyone could talk to everyone. Dick Wilbur was more interested in talking to Dianne about her gardening” than impressing aspiring poets.

The conference attendees had wide-ranging interests (or at least were receptive to Gioia and Peich’s wide-ranging interests). One of the signature components of the conference was a classical vocal concert series, which in 2000 featured compositions by West Chester native Samuel Barber, “arguably the greatest American classical composer,” according to Gioia. This was the fruit of a collaboration with West Chester’s Samuel Barber Society and was a highlight of the conference’s music program. Another highlight came in 2010 when Natalie Merchant performed “Leave Your Sleep,” verses by 26 poets set to her original music.

This musical component reflected the conviction that poetry and song are sister arts. “All poetry was sung or chanted in the ancient world,” Gioia said. “It seems to me that if you were studying poetry, especially formal poetry, it had a deep connection to song.” That connection is obscured to the point of erasure with the loss of meter, which tells a reader where to place emphases when reading or “scanning” a line of poetry.

It is easy to see, based on the idea that poetry exists preeminently in the human voice rather than on the page, why a gathering of poets in one place was such a vital enterprise.

View of Aralia Press. Photo courtesy of Michael Peich.

Two men, a bottle of pinot and a plan

Peich and Gioia are very different, but oddly compatible. They are both mold-breakers, hybrid thinkers: Gioia is a Catholic poet-executive. Peich is a Protestant craftsman-professor. They are both tall and athletic (Peich played college football). Gioia lays out broad, architectonic certainties in a gravelly baritone. His career is almost like a series of battles in a war: He served on the General Foods C-suite, quitting in his forties to pursue a literary career; then as pugilistic champion of the new formalism in the pages of The Atlantic and other periodicals; then as chair of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Peich, on the other hand, led a quiet life in West Chester as an English professor and, later, a printer-publisher. He too speaks in passionate certainties, but they are certainties about details: like how he came to prefer Bembo type over Spectrum, or the use of the golden mean in sizing margins in relation to a block of text. Of late, he has been gaining notoriety on YouTube as a baseball historian.

In bonding over Weldon Kees, the pair found that their tastes in poetry more broadly overlapped. “I wasn't a big fan of a lot of the contemporary poetry I was reading,” Peich told The Fold. “It didn't make sense to me. It was impenetrable. It was too precious. I was tired of reading about people getting up and scrambling their eggs and smoking a cigarette and working terrible jobs.”

Gioia, a poet as well as a critic, shared Mike’s notion that American poetry had rarified itself out of an audience. His heart went out to poets who knew that something was wrong, who found their first urges to compose in the songlike speech of poetry snuffed out by the aversion to rhyme and meter and rampant in journals and in the academy, and who found themselves alone in their creative practice.

“When I created the West Chester conference,” Gioia told The Local Fold, “my model was St. Augustine’s City of God. My objective was to take poets, especially young poets, who were stuck in the city of man—you know, the creative writing industry, academia, all that nonsense—and to bring them into the city of God for a week, which is to say, a city that does not live by the rules of man, is populated by people who have elected to live by different rules.”

Over a bottle of pinot noir at Gioia’s parents’ Sonoma, California, home, the two friends sketched out the rudiments of the first conference. They decided to hold it at West Chester University, where Peich was chair of the English department.

The first conference, held in the summer of 1995, drew about 70 poets, many of whom traveled great distances and stayed in the university dorms. No one knew quite what to expect. There were seven workshops on various elements of poetic form, a keynote by Richard Wilbur and effortless camaraderie. At the concluding ceremony on the last day, Peich told The Fold, “they literally wouldn’t let Dana and me out of the room unless we promised to do it again next year.”

Revolutionary students

At its peak, from 1997 to about 2014, the West Chester University poetry conference was bringing 300-400 poets to the borough every summer. Some were already accomplished in working with traditional forms, others had advanced degrees but had never received serious training in verse craft. None were there simply to add a line to their C.V.

“The quality of our students was remarkable,” Gioia recalled. “I once taught a class on experimental form; all but one of my students had published at least one book.”

If the level of accomplishment was already high, it was nonetheless true that careers were made at West Chester. “I’ll give you an example: Alicia Stallings was someone who came to West Chester as a student and was printing her own little books,” Gioia told The Fold, referring to A.E. Stallings, arguably the best-known poet writing in formal verse today. “I kept track of people, and every year she got better. I brought her onto the faculty and eventually made her a keynote. Now she's the first American ever to be Oxford professor of poetry.”

Stallings was one of several students of the conference who would go on to reshape the fortunes of poetry in America. The 1980s had seen a return to form by younger poets. Some went largely unnoticed, but a few, such as Brad Leithauser and Vikram Seth, met with widespread critical acclaim—and even sold books. The backlash from the academy and the literary establishment was fierce. Labeled “new formalists” by their opponents, these poets, Dana Gioia among them, were accused of a “dangerous nostalgia” by critics who attempted to drive a wedge between the new practitioners of formal verse and the uncontested masters from preceding generations, poets like Richard Wilbur and Robert Frost. The new formalists, it was alleged, lacked vision and made up for it with adherence to received norms of craft.

Those wittingly or unwittingly labeled “new formalists,” for their part, simply soldiered on, finding inspiration, as Frost had, in overcoming the stubborn resistance that meter posed to “creativity,” and gleaning joy in employing trochaic substitutions, last foot feminine endings, and other tricks of the trade to make their lines sound conversational and effortless. From time to time, they were roused to respond to allegations that they were aesthetic Reaganites or crypto-reactionaries, but for the most part they just did what they loved: writing poetry or, as the Roman poet Horace had put it a couple thousand years earlier, “locking up words in feet.”

There was no final confrontation in these “poetry wars.” As time went on, rhyme, meter and narrative simply became tools available to American poets if they chose to pick them up and dust them off. Those formerly dubbed new formalists were accepted into the big tent of American poetry. And yet, with this relative victory, as with all victories, there came a slackening in the understanding and practice of the arts and disciplines that had been employed in the fray.

“The official view of new formalism is that it was made extinct,” Gioia said. “The truth of the matter is that we had it incorporated into the fold. Now, all these poets are writing sonnets—and they’re not writing them particularly well because they didn’t study with us. But rhyme has come back in. That’s an abstract way of saying that we changed the zeitgeist, which we did. But the more germane thing was that we took hundreds, probably over a thousand orphaned poets, and we gave them a home. We gave them a readership. And we developed them, and some of these people are now significant poets.”

These adopted orphans, Stallings one of the foremost among them, would reintroduce a rigorous application of craft and a mature aesthetic vision into the anything-goes world of American poetry in the new millennium.

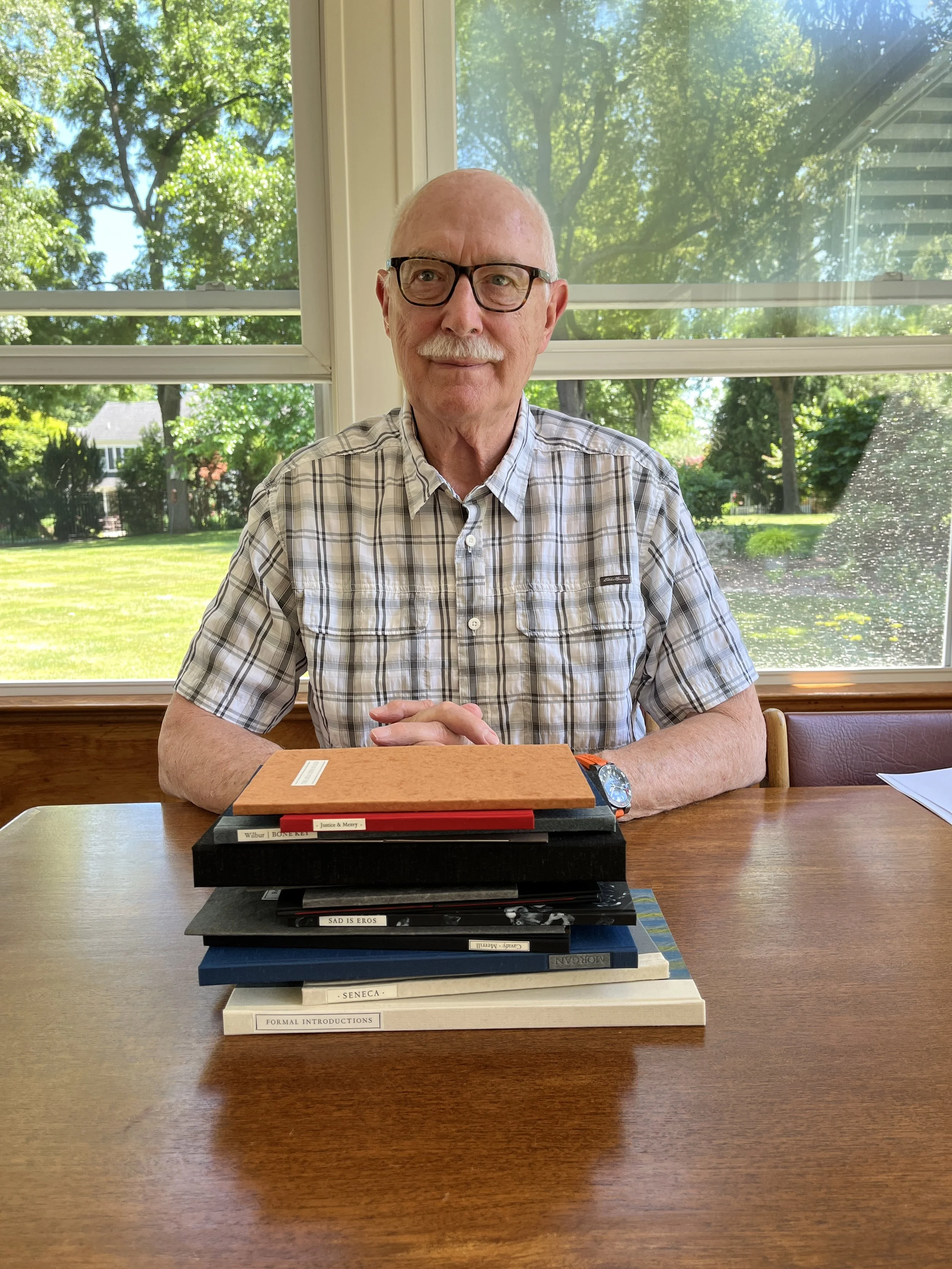

Michael Peich and a stack of Aralia Press books. Photo by Matthew Kirby

Aralia Press: The well-ordered page

Years before Peich and Gioia came up with the conference that fruitful night in Sonoma, they collaborated in bringing well-crafted poetry into print in equally well-crafted books. “The poetry conference grew out of my work at Aralia Press,” Peich told The Local Fold. “I was publishing all these writers who were employing traditional craft.” Gioia was the press’s unofficial editor.

Peich founded Aralia in 1983 after learning the traditional craft of printing and typography from commercial printer and typographer John Anderson. The librarian at West Chester University at the time, Frank Helms, had a fondness for handmade books and gave Peich the use of a room on the 5th floor. There Peich set type by hand—as printers had since Gutenberg’s invention of movable type—and printed pages on a Vandercook cylinder press on high-end paper, some of it handmade.

The texts that were to be honored with this laborious treatment were selected with care. “I learned early on from a guy named Harry Duncan, who was a masterful printer: The worst experience is producing work by someone whose work you don’t like. Because then it ceases to be a joy and becomes a task,” Peich told The Fold. “That, I can honestly, say happened only once.” In the beginning, Peich sought out texts from poets he admired. After a few years, inquiries began rolling in from poets at all stages of their careers.

Once a manuscript was accepted, Peich read it with care, looking for the seeds of the physical object in the text itself. “When you get a manuscript, you have dozens of problems to solve: What’s the type going to be? What’s the paper going to be? Is there going to be an illustration? What color are you going to use? What layout will you create? Is it going to be a wide book, horizontal, narrow?”

Like the West Chester Poetry Conference, Aralia Press was a labor of love: “I not only wanted to publish unknown, non-commercial writers, I wanted to publish them in editions that were not commercial,” Peich said.

Aralia’s first book was Dana Gioia’s Summer. The slender chapbook was—only narrowly—the second book of Gioia’s career as a poet. Next came Two Prose Sketches by Weldon Kees—the poet who had brought Peich and Gioia together—edited and introduced by Gioia. These volumes were followed by an astonishing list of original titles by contemporary American poets such as Philip Levine, David Mason, Mark Jarman, Richard Wilbur, Donald Justice, H.L. Hix, Marilyn Nelson, Timothy Murphy, Mary Jo Salter, Brad Leithauser, David Yezzi, A.E. Stallings, Timothy Steele, Rhina Espiallat and Christian Wiman, as well as works in translation by C.P. Cavafy, Mario Luzi, Paul Valery and others.

Aralia’s 1994 anthology Formal Introductions, edited by Gioia, serves as good barometer of Peich and Gioia’s tastes on the eve of the first poetry conference. In his introduction, Gioia calls it “the first anthology to present New Formalism in its true form, an innovative and iconoclastic generational movement.” In it, poems range from the filigreed naturalism of Melissa Green’s “August” to the measured snark of Jack Butler’s “Attack of the Zombie Poets.” Absent is any of the breathless self-importance that characterized much contemporary verse. This is poetry of the public park rather than the hothouse. The fact that this slender, hand bound book, of which only 210 copies were printed, was able to define the spirit of a moment in American literary history testifies to the power of the small press.

Aralia published 107 titles in its 36-year run, won awards for design and exhibited books around the country, including several shows at the New York Public Library. It was unique among small presses for its fastidious design, its editorial focus and its organic connection—largely thanks to the poetry conference—with a flesh-and-blood literary community. In a digital age, Aralia demonstrated the enduring power of the handmade object to move the human soul.

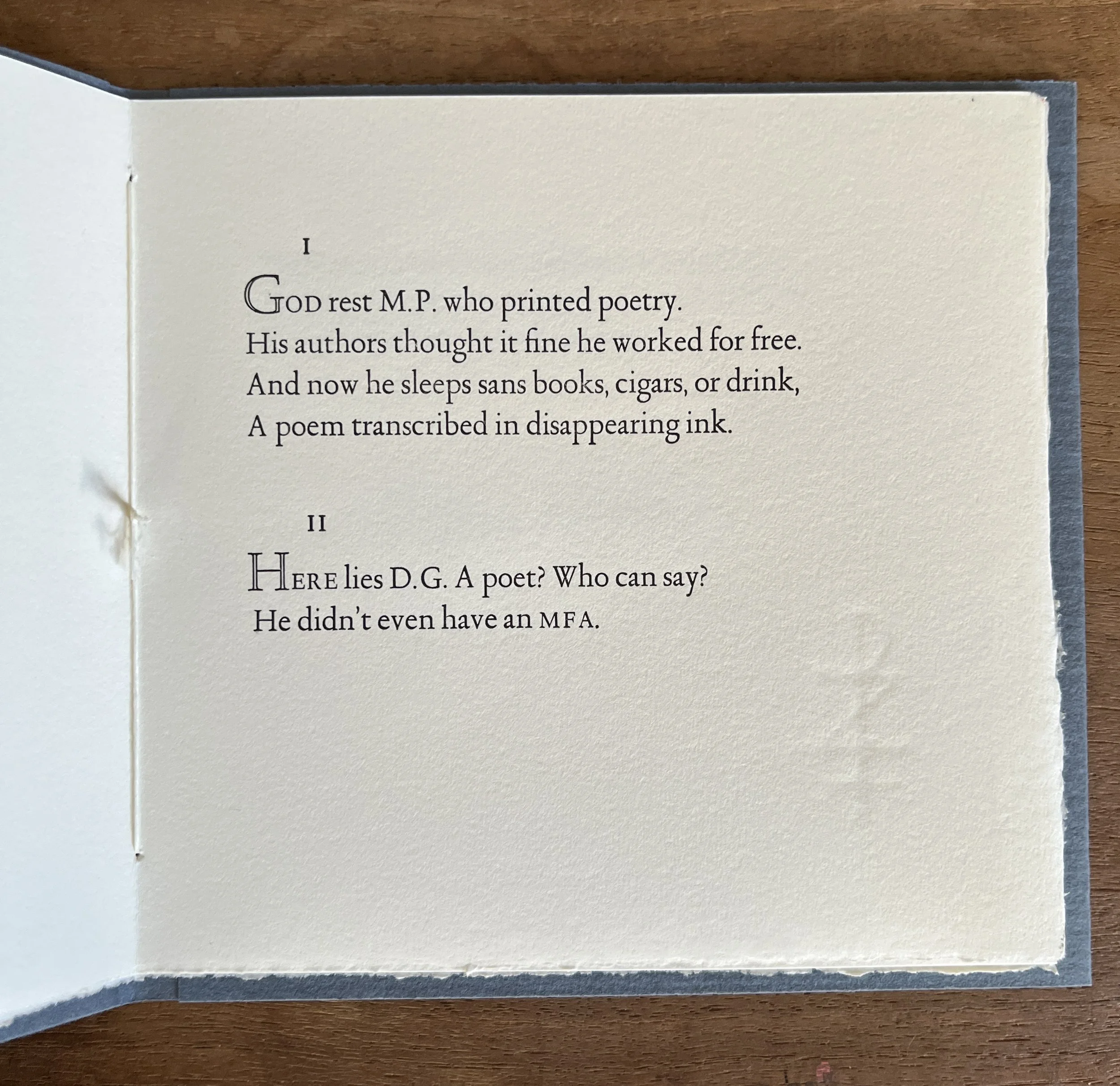

Aralia’s fitting last title, the tongue-in-cheek “Two Epitaphs,” was written by Dana Gioia. Here is the text in its entirety:

I.

God rest M.P. who printed poetry.

His authors thought it fine he worked for free.

And now he sleeps sans books, cigars, or drink,

A poem transcribed in disappearing ink.II.

Here lies D.G. A poet? Who can say?

He didn’t even have an MFA.

“Two Epitaphs.” Photo by Matthew Kirby

The fortunes of ‘West Chester’

“Most cultural events and institutions have a great epoch and then they sink into mediocrity or go bankrupt,” said Gioia, who stepped aside from conference leadership when he was appointed chair of the National Endowment for the Arts by President George W. Bush in 2003. “We had a great nearly 20-year run, and as a result we were able to bring form back into American poetry. It went from a forbidden thing to something you were allowed to do.”

Michael Peich left the conference when he retired from the university in 2010. He attended the conference for the last time for the twentieth anniversary in 2014. Neither founder has gone on record about the trajectory of the conference following their departure.

The Daily Local News reported that the 2015 conference was cancelled when the director of the poetry center at the time, Kim Bridgford, was “reassigned to full-time teaching.” Around this time, the university administration seems to have taken an increased role in the management of the conference, a departure from the first 20 years when their primary involvement was simply to provide the facilities and attend the packed banquets. (Under Peich’s directorship, the West Chester University Poetry Center, which he founded and which ran the conference, received a $300,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. He and Gioia were required by the terms to match the grant three-to-one by fundraising, and they did.)

West Chester University administrator Cyndy Pilla, who currently manages the poetry center, told The Local Fold that the last “true” West Chester University Poetry Conference was held in 2019. It has since been “rebranded” as a one-day “festival” and rescheduled from June to April in order to attract students, who leave campus during the summer months, and to coincide with national poetry month. Attendance by outside poets has dropped nearly to zero.

Jen Bacon, dean of West Chester University’s college of arts and humanities, said in a statement to The Fold, “We continue to experiment with methods to bring the Poetry Center’s mission to life and we will always make sure that our students have opportunities to engage with form and with expert poets who can help them hone their skills.” Bacon noted that, “This year, we were able to bring Ernest Hilbert in for a masterclass,” referring to a poet known for employing traditional forms.

However, according to Pilla, “Younger poets want more of a freeform kind of thing. They don’t want the structure, so we don’t focus as much on the form as we used to.”

The West Chester University Poetry Conference had been a labor of love, fiercely idiosyncratic, deeply inspired. In that form, it would not long outlast its progenitors.

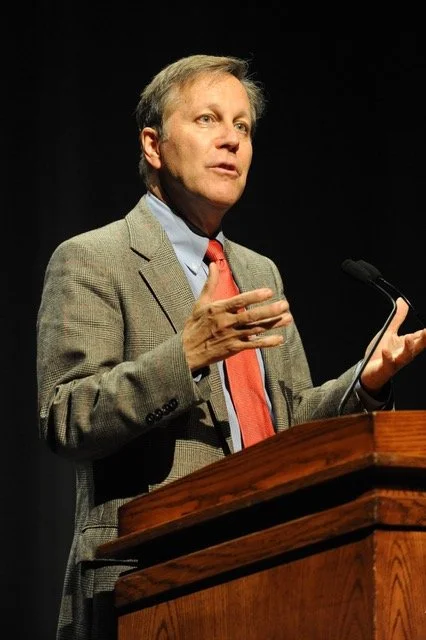

Dana Gioia speaks at the West Chester University Poetry Conference. Photo courtesy of Michael Peich.

West Chester’s progeny

“West Chester” was marked by a spirit of collegiality and commitment to craft, a spirit that could also be uncompromising in its tastes and that ran contrary to academic bureaucracy and literary careerism. “It was magical,” Peich said. And it was an experience that spawned at least two efforts to recapture that magic. The first is the master of fine arts program at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas, founded by poet James Matthew Wilson and novelist Joshua Hren.

“When we founded the MFA program at the University of Saint Thomas, we drew on the experience of West Chester in several ways,” Wilson told The Local Fold. “We wanted our program to offer comprehensive and expert instruction in verse craft drawing on the work of West Chester regulars such as Timothy Steele and Bill Baer.”

Wilson, who was encouraged by Peich to come out to West Chester during his days as an MFA student at the University of Notre Dame, added that “We began our Summer Literary Series hoping to do for Houston what the West Chester conference had done for the Philadelphia area: to create a free and open program for the general public and to invite all with an interest in literature to join us on campus for evenings during the summer.”

Second, Dana Gioia himself has drawn on his experiences at West Chester to launch what is arguably the most influential arts and culture conference in the American Catholic Church, the Catholic Imagination Conference, first held at the University of Southern California in 2015. Once again, Gioia wanted to bring people out of the city of man and into the city of God:

“(The West Chester University Poetry Conference) became the model for the Catholic Imagination Conference. Having done this for 20 years, I understood conferences in a way I didn’t before. You have the stated purpose of the conference, which was to do intellectual things, but the real purpose was to bring Catholics from all over the country together—writers and literary people—so they could see how many of them there were. They were all the only Catholic people on the faculty, then, all of a sudden, they found themselves with 300 other smart, curious and faithful Catholics.”

But Gioia, as always, was not content merely to bring people together. He was mustering troops to take the next hill. “Most people have no idea what’s going on in culture at any time. And that goes for most Catholics,” he told The Fold. “That’s because our culture doesn’t give much arts coverage, and what they do give is all political. And Catholics have been lazy: They’ll complain about it, but they won’t do anything.” Accordingly, Gioia hopes to do for Catholics in the arts what he and Peich did for poets: wake them up to the ways God empowers man to co-create with him, always ordered by a Logos that seems to elude bureaucratic control.

1 Gwynn, R.S. and Lindner, April, editors. “The West Chester University Poetry Conference: A History.” Kelly-Winterton Press. New York. 2004.