Forsaken silence, sacred song

Icelandic film writer-director Hlynur Pálmason’s harrowing Godland (2022) is a moving adventure epic both physical and existential. Godland follows young Danish Lutheran priest Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove) on a perilous cross-country journey to build a church and congregation in a remote outpost along the colonized southeastern Icelandic coast. While set in the late nineteenth century, the award-winning film has something to teach us today about God, faith, and evangelization when taken on by the physically, emotionally and spiritually fallible—that is, all of us.

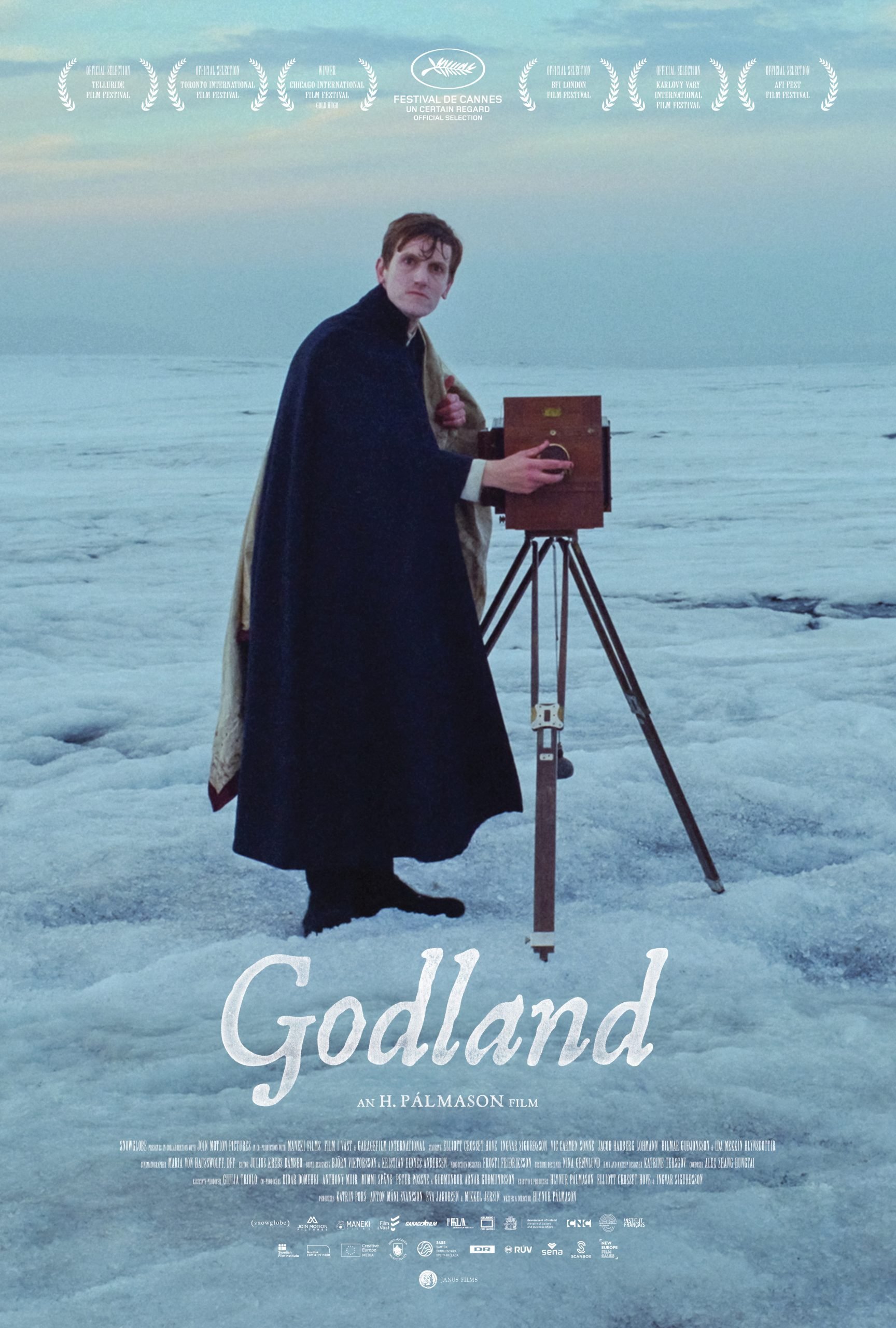

Several of the film’s reviews have compared Godland to Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God. In its questing and largesse, the film also calls to mind Herzog’s 1982 adventure-drama Fitzcarraldo, which follows a man’s expedition to build an opera house in the middle of the jungle. Herzog’s and Pálmason’s films both used documentary film techniques over multiple years of shooting. Godland cinematographer Maria von Hausswolffs captured the beauty and treachery of Iceland on 35mm film, lending the film historical authenticity in form as well as story. Both films claimed roots in historical fact. Godland’s roots—found wet plate photographs taken by a real nineteenth century Danish priest—are fictional but provide a compelling hook. Both protagonists fight immense environmental and psychological foes and are in danger of losing their faith, their minds, and their lives along their journeys. Both films are steeped in Christian imagery—and in tragedy.

It’s important to note that the title of our film, Vanskabte Land in Danish, translates to “wretched land,” or “godforsaken land,” rather than “Godland.” From a quick internet search of Iceland’s past, I learn that late nineteenth century Iceland was characterized by its struggle for independence from Denmark and by economic stagnation and emigration. Iceland is both caught, and ignored, it seems. Isolated in the volatile North-Atlantic Ocean, the country’s sparse population is tough enough to subsist on some fishing but mostly on farming forbidding, infertile terrain. Home rule in Iceland won’t be established until 1904, with the Icelandic republic formed forty years later.

Enter the proselytizing Dane. If God has forgotten this treacherous place, the ambitious Pastor Lucas aims to build a house for Him to settle in. (If you build it they will come?) But between Lucas’ weak physical constitution and ascetic—even selfish—fervor, we fear he has barely a prayer of getting through to the locals.

The missionary zeal of the 19th century and the “new evangelization,” a buzzword of late in our U.S. Catholic Church (and today’s evangelization efforts elsewhere along the Christian continuum), are vastly different. However, the aim is the same: bring believers into the fold. Church leaders and laity alike decry the difficulties of leading people to God in our secular world, treacherous not by nature’s design so much as by man’s. But the good news (and Good News) is that God is everywhere and always has been—in the secular and the sacred, in the turbulent world and in our turbulent souls. We are, every one of us, called to be holy. But how best to communicate that to the unindoctrinated?

Before his journey begins, Lucas is forewarned by his bishop (Waage Sandø) about the perils that could befall him on his way: an erupting volcano is causing rising waters, and the endless summer light can drive a man mad. But those are only the external, natural elements. “You must adapt to the circumstances of the country and its people,” he says, and “think about the Apostles sent to preach to the world.”

Lucas doesn’t adapt. His attempts at making nice with the group of Icelanders he travels with, of learning more than a handful of their words from his translator (Hilmar Guðjónsson), are few and weak. Mostly, the priest is a quiet man set apart, not particularly pastoral. His friendly associations he saves for the Danish family who puts him up at their homestead: widower Carl (Jacob Hauberg Lohmann), his marriageable daughter Anna (Vic Carmen Sonne), and curious younger daughter Ida (Ída Mekkín Hlynsdóttir).

Any apostolic commitment to demonstrating to the Icelanders the power of God is reserved for the camera Lucas lugs on his back, more magic than holy, with which he photographs the land and its people. The priest is an image-taker, like many colonists before and since, his camera keeping him at a remove, and at times literally (if necessarily) in the dark.

The film treats viewers to Iceland’s epic scenery—great ravines, waterfalls, and volcanic action—along with Pálmason’s signature, stunning and intimate “portraits.” A close-up of Lucas in his tent along the journey finds him experiencing a crisis of faith, or, more to the point, confidence. “Heavenly Father,” the priest prays. “Things are not going as planned.” Lucas is ravaged inside and out—with sleeplessness and fatigue, and with doubt. “I don’t have a voice,” he prays to God in whispers.

In his director’s statement for the Cannes Film Festival: Pálmason calls Godland “a film about a journey into ambition, love and faith and the fear of God and the need and want to find your place in all this.” It’s about “what divides us and what ties us together.”

Though troubled, Lucas doesn’t try to connect with his journeying party. When he does speak to the Icelanders, he utters a refrain, almost a tic: “I don’t understand you” becomes a wedge between the missionary and his mission, between colonizer and colonized, that’s only driven deeper as tensions build.

Behind it all is Alex Zhang Hungtai’s haunting score of instrumental, ambient sounds that beautifully mimic the shrieking wind of the harsh seascape and landscape. Then there are the horses’ hooves, rushing rivers, and lava flows that make their own soundscape.

“There is also quite a lot of singing throughout the film,” notes Pálmason in an interview with Marta Balaga for the Festival: “Ragnar with his old poems and the introduction of the sisters, when Ida sings a murder ballad on her way to the house and then Anna sings by the piano at the end of the dinner scene.”

Folk songs humanize the score, revealing a local culture attuned to nature, love, longing, and loss—that is, some of God’s very best work.

Though the Lutheran Church is sometimes referred to as “the singing Church,” Lucas sings not a note in the film. Not at a funeral nor at a wedding. Not in lament nor for love of (wo)man or God. How glorious the moment when Lucas dances at a wedding celebration in the roughed-out church! Still, he can’t or won’t use his authoritative voice to make a joyful noise unto the Lord, or entreat others to do the same, missing out on a powerful ministry.

It’s Ragnar, the trekking group’s guide, who sings. In fact, he is singing in his deep baritone when we first meet him. A Saint John the Baptist or Desert Father type, minus the religious zeal—close to the earth, his horse, and his dog—he knows well the terrain and its people. Ragnar works as Lucas’ foil and perhaps our model of a humble, fledgling faith, the kind to sing about.

He pulls fish from the river. He orders a lamb slain to feed his crew. He cares for the horses, carrying heavy loads along the journey to the church building site. Early in the film, he orders the large cross for the church roof to be cut in half, distributed over two horses’ backs. It isn’t, a fact that spells serious trouble for the journeying party. While Ragnar might not be Christian, Christian symbols abound around the man. But when he asks the priest with sincerity how to become a man of God, Lucas basically brushes him off, devoting his attention instead to his letters, photographs, and lonesome prayers.

Preaching to the likes of Ragnar is not something the pastor will humble himself to do. Nor will he conduct a marriage ceremony in a half-built church. For a man of God, Lucas is a rigid man. Still, he succeeds in his task to have the church erected, a much smaller cross than the original one hammered up top, an opening hymn played at the first service.

“To sing is to pray twice” is my favorite misquote, often attributed to Saint Augustine. Rather than sales promotion, the doubling is likely more about sung prayers—praying both with one’s heart and soul—or perhaps about praying in community. Singing invites listening. As a member of my Catholic parish choir and a Mass cantor, if I have a charism, singing is it. On the best days, singing makes me feel connected to another, ethereal realm, but more importantly it connects me to my fellow journeyers here on earth. “Go to the world,” we sing, a hymn of apostolic entreaty: “Go in to every place / Go live the word of God’s redeeming grace / Go seek God’s presence in each time and space / Alleluia!”

Prayer, quiet and contemplative prayer of the soul, I struggle with. I know I’m not alone. There is never enough prayer of any kind in this world, said or sung. Not even for Pope Francis, whose intention for November 2023 was: Pray for me.

There is but one Christian hymn in the Godland soundtrack; however in listening for the human song that interrupts the film’s austere score, I find the tender center in the fairly brutal external and internal setting of this film. I find God at his good work, lifting voices.

Voices young and old, high and low—the act and manner of singing seem at least as important as the song selection in Godland. Ragnar’s songs include a recitation of names, all dead, perhaps, a sorrowful litany. Ida’s singing of a murder ballad in her sweet, young voice draws light and dark together. So too does Anna’s singing of “Det er hvidt herude” (“It is white out here”), a poem by Steen Steensen Blicher composed to a tune by Thomas Laub, which tells of Candlemas, the severity of winter, of silent birds, and the long wait for spring. Beauty and treachery, life and death, are at every turn, inside and out in Godland. The only possible way through, it seems, is together.

In other key moments of the film, the human voice is heightened by accompaniment. There is merry music-making with accordions on the church lawn after a wedding, a small organ played in the church, and an untuned piano played in the home of Carl, Anna and Ida. Accompaniment takes two musicians, at least, and Where two or three are gathered … Song marks sacraments performed, connections forged in a world too often divided.

What sets off the final and fatal climactic moment in Godland are those three powerful words—“Pray for me”—both an entreaty and a prayer. Ragnar asks for his photograph to be taken, and Lucas denies him yet again, denying the man faith, God, and sacred human connection here on earth. Then comes a moment of sincere confession. Ragnar runs through a litany of his sins: being cruel, being selfish, being a coward, and worse. After each, he whispers to the priest, “pray for me.” The sea rages beyond them, a turbulence never to be tamed between these kinds of men, perhaps both frustrated prophets. The scene and the film end in silence. Pray for us all.