Envy - The Only Sin With No Pleasure

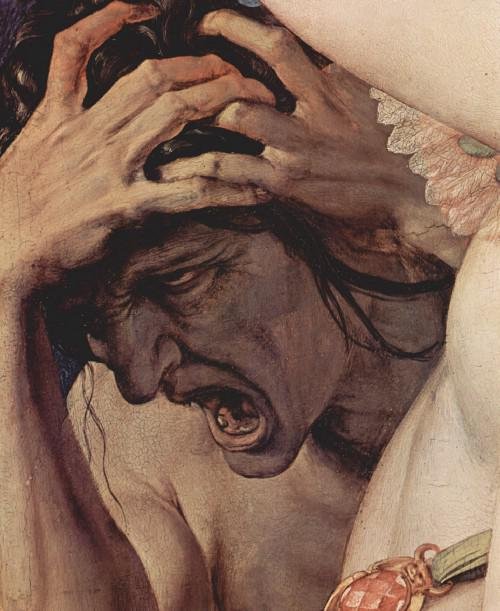

The Yorck Project, 2002 (Wikipedia Commons)

Bertrand Russell, the brilliant English philosopher and atheist, did not believe in sin — yet argued that Envy is, “The most unfortunate,” of all human passions:

Not only does the envious person wish to inflict misfortune and do so whenever he can with impunity, but he is also himself rendered unhappy by envy. Instead of deriving pleasure from what he has, he derives pain from what others have.

Traditionally ranked just below Pride — the deadliest of the Seven Sins (or passions as he called them) — Envy seems unique in its absolute inability to give us any real pleasure. It is, argues Christian philosopher Jeff Cook, the most miserable of the Seven. Whereas Lust, Greed, Anger, Sloth, Gluttony, and Pride all offer the sinner the pleasures of sex, money, power, ease, food, or self-esteem, Envy offers the sinner nothing but misery. Even unlike Greed, its closest relative, it refuses to be satisfied with more until you — the envied one — has less; a scenario which could only happen in your private kingdom.

Why are we then so easily infected by this miserable green “virus” which provides so little reward? I would like to explore this unique form of misery, and why we refuse to protect ourselves from a sin which offers such deep misery and so little pleasure.

The Parable of the Envious Son

Jesus’ most famous parable in Luke 14. 11–32 may give us a clue. It is commonly titled “The Parable of the Prodigal Son,” a title which focuses primarily on the deadly sin of Greed (represented by the greedy or prodigal younger son) rather than the sin of Envy (represented by the envious older son).

There is a strange and beautiful rendition of this parable in Moscow’s Museon Park of Sculptures: The prodigal son, hewn from two blocks of granite (the Greed from which he struggles to emerge), clings to his father in repentance, while the older son, representing Envy, is barely visible behind the father’s right shoulder…

Yet this older son — who only appears at the end of the parable — is filled with resentment and misery because his father welcomed back his wasteful younger son by slaughtering the delicious “fatted calf.” But note this: he is not miserable because he didn’t get a fatted calf; he is miserable because his younger brother did. And not even a thousand fatted calves would make him happy now. He does not want just a fatted calf — he wants his younger brother to not have a fatted calf. And the last words we hear from him is this bitter outburst to his father: “When this son of yours came, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fattened calf for him!’

The father tries to give the story a happy ending by reminding the older son that he already owns all his fatted calves. But there is no response from his son. The parable just ends. Yet this is clearly a parable of two deadly sins: the Greed of the younger, and the Envy of the older. And Jesus make it clear that Envy is the worst. Not only is the envious brother more miserable than the greedy brother, but he remains unreconciled to his father. And the bitterness of his Envy appears to have a tragic ending.

Greed may have led the younger son to a humiliating end in a pigsty — but his misery is short. And he is able to see his sin far more clearly than the envious brother can, and his repentance is therefore rapid. Envy, on the other hand, sustains the older son’s dignity over a long and miserable time-period.

Greed is like a disease which spreads rapidly — causing us to cry out for mercy and find healing. Envy is more like a cancer which spreads slower and insidiously inside the body — protecting our dignity while it ravages our joy. Greed can be shared amongst friends; Envy must always be hidden — it is not a sin one wants to share with others. Greed simply wants more “stuff”; Envy wants others to have less stuff.

Even at its most “noble,” Envy wants — no demands — that others are given their just punishment. Which is why the Father’s mercy to the greedy younger brother drives the older brother insane. His yearning for justice has been denied. And perhaps that is why we cling so tenaciously to this miserable sin: we, too, yearn for justice. But Jesus’ parable subverts our yearning for justice and fairness by telling a story in which the “bad” younger son receives mercy, and the “good” older son, who continued working faithfully in his father’s fields, is denied the justice he yearns for.

We can only imagine the offence this parable must have triggered amongst the stable farming community Jesus was talking to: the bad son who wasted his father’s money is celebrated! And the faithful older son who woke up early every morning and worked till sundown every night receives nothing. Where is the justice in this story? There is none.

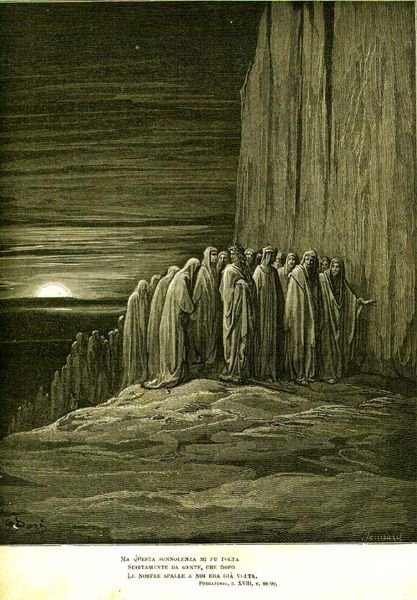

Gustave Dore: The Envious, blinded, lean on each other for support on the 4th Terrace of Mt. Purgatory (Wikipedia Commons).

And that is Jesus’ point. In the Kingdom of Heaven there is no justice. Which is why the envious so often refuse God’s invitation to Heaven. Envy demands justice (not mercy). We want to deserve our place in Heaven. We want to work for our reward. We don’t want handouts! And Heaven would therefore be a very offensive place for the envious: a place filled with lazy, greedy, smelly losers — all of whom have repented. And none of which deserve Heaven.

In How Dante can Change your Life, Rod Dreher describes how reading this parable in the middle of a family crisis helped him to finally recognize the misery which this little virus of Envy had been inflicting on him and his family for so long: this parable, he said, described his own family.

His dad had always seen him as “the prodigal son” who abandoned the family and wasted his talents in the secular world of New York. But Dreher, on the other hand, began to recognize his father as a cruel subversion of the merciful father in Jesus’ parable. Whereas the father in the parable embraced his son when he returned, his father had never embraced him when he gave up a lucrative job in New York, and returned to be his family in the South. And this had created a deep resentment within Dreher. Envy had infected him. And he began to realize that dwelling on “the pain, the rejection, and the sense of injustice” would keep him stuck in illness and misery for as long as he nursed this wretched little virus.

On Dante’s Mt. Purgatory, the envious have their eyes sewn shut with wire. It sounds like a terrible punishment, but these sinners choose this pain because they understand that Envy is caused by a distorted way of seeing (the root word for envy is the Latin word videre, to see). And the only cure is in blinding their bent vision.

As blinded climbers, the envious are therefore forced to really “see” their fellow climbers for the first time — to lean upon each other for survival without the ability to pre-judge, and therefore distort each other. All become equal on this blind and humbling mountain, where neither color nor class, rich nor poor, ugly nor beautiful, make any difference. It is really hard to see each other clearly in Earth’s murky spiritual atmosphere. And things become much clearer and sharper at higher altitudes on Dante’s Mt. Purgatory.

Even Bertrand Russell suggests a cure for the misery of Envy: “Whoever wishes to increase human happiness,” he argues, “must wish to increase admiration.”—the exact opposite posture of Envy, and very difficult with our bent vision.