About that Padre Pio film…

As Dappled Things readers know, one age-old dilemma for artists is the line between portraying evil and being complicit in it. This line will appear differently in different art forms according to the materials they use. For the cinema, that line must be drawn more sensitively and sharply than, say, for the written word, due to various factors, including the almost unparalleled immediacy and illusory power of filmed images, as well as the real human actors involved, and film’s historical status as a popular art form.

It is worth noting in this connection that the institutions of the Legion of Decency and the Hayes Code had no precise parallel in other art forms. A contributing factor in their founding was surely a recognition of the unique power and realism of cinema. The movies have a long history of crossing the line between portraying and perpetrating evil. In more censorious times, films could get away with a degree of titillating content under the guise of a moral lesson. Even without this kind of cynicism, it happens not infrequently that a filmmaker who intends to portray evil as evil, yet lacks the required moral and artistic sensitivity, ends up simply obliterating the line by committing the evil himself.

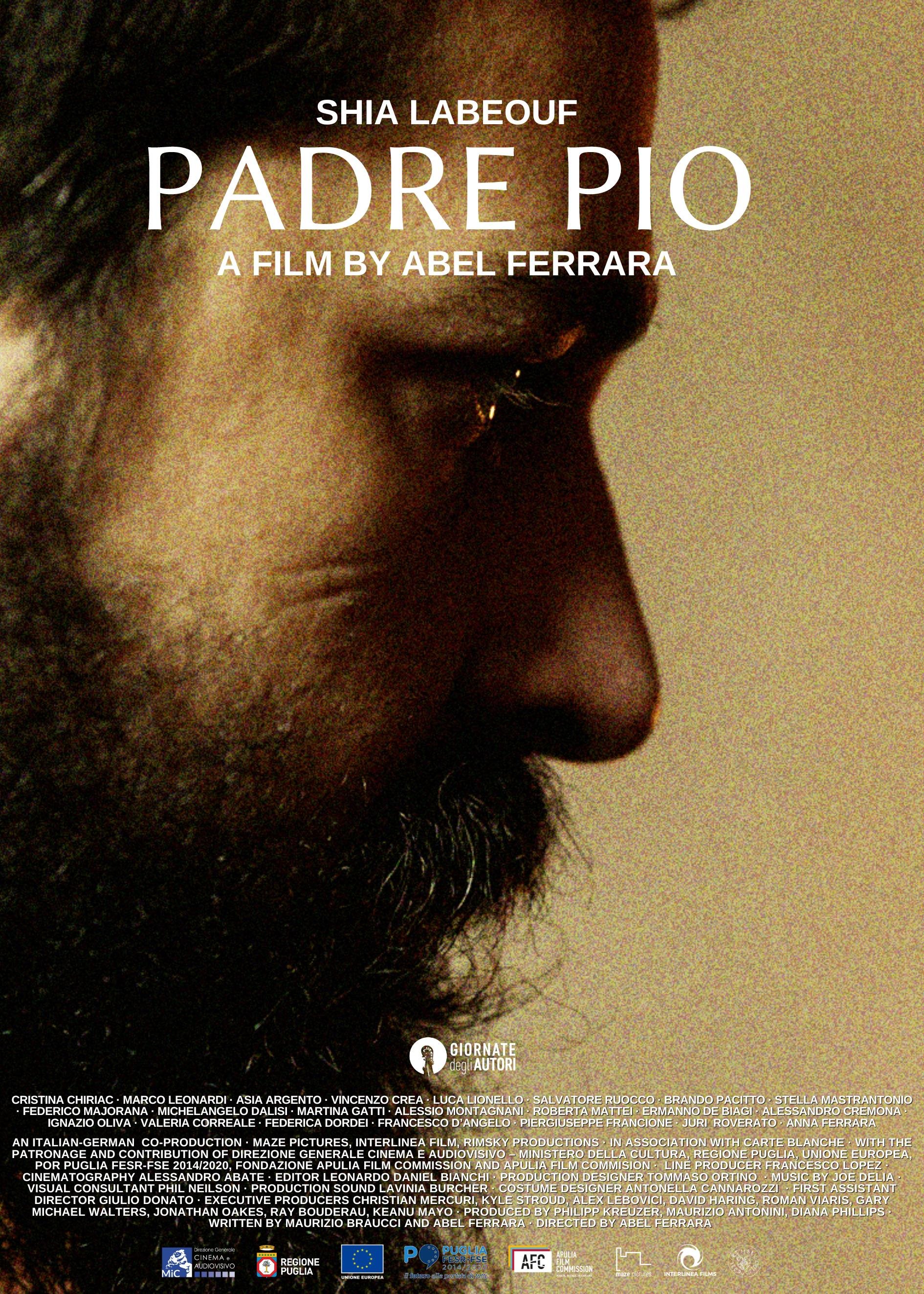

Such is the case with a scene in the new film Padre Pio, directed by Abel Ferrara and starring Shia LaBeouf. Regardless of his artistic intent, Ferrara has crossed a line, resulting in a moral and spiritual enormity outweighing anything good the film otherwise might have had to offer, and rendering it unwatchable by any conscientious Catholic.

To the point, then: in this scene the Devil appears to Pio in the form of a naked woman, lasciviously kissing an icon of Mary. This will be enough to stop many readers from seeing the film, and rightly so. But perhaps it is worth a little more reflection on the objective evil that has been done here, regardless of intent and regardless of context – and, too, the resulting artistic failure.

First: what was Ferrara trying to accomplish, on the best interpretation? The scene is one of a number portraying the interior and supernatural trials of the young St. Pio. I do not know enough about Pio’s life to know if he was faced with this particular demonic vision; Ferrara did consult with Capuchins, so let’s suppose for the sake of argument that this was a real incident rather than something Ferrara invented because he thought it would be neat.

What does the devil do to Padre Pio here? He wants to wound him by showing him a mockery of those he most loves: his Mother, and by extension his God.

So, then, what has Ferrara done to us? He has shown us a mockery of those we most love. Now we do not need to be holy enough to merit an extraordinary demonic attack. We simply need to unwittingly turn on a film about one of the most beloved saints of the past century, in order to be confronted with a deeply wounding and perhaps even traumatizing image. If the devil really did this to Pio, Ferrara has, at best thoughtlessly, extended that demonic attack into the next century, against viewers less spiritually fortified than St. Pio.

An artist in any medium should know the properties, the weight and density of the material he’s working with, including its capacity to defy his intentions. A visual artist should know that the image can have an adverse effect even on a beholder who fully understands the filmmaker’s intent. Images have power in themselves, regardless of context. One would hope that artists would know this better than anyone, but artists today are arguably less sensitive than others, because being an artist is in our culture tied to being “open” to every kind of transgression. Ferrara is best known for the extreme images of sex and violence in his earlier work; an extremism he now attributes to his former drug addiction. Praise God that a man can change, but even sober, the desensitizing effects on his imagination remain.

An artist should also understand that images cannot be unseen, and that their impact can be greatly disproportionate to the amount of time they take up. An image shown for less than a second can be remembered long after the rest of a film has been forgotten.

For those unfamiliar with the art of filmmaking or what happens on a film set, some discussion of that may further bring home the reality of the offense. Choices were made here – there are a myriad of ways you can film something. Perhaps there’s a way this film could have implied that such a sacrilege was committed, without showing it explicitly. But here, the director chooses to make cuts and focus the camera in such a way that the pornographic quality of the action is all too evident.

The image in question is bad enough on its own. But Ferrara has not merely shown us something; he has not just created an image, like a painter or CGI artist. Those of us unfortunate enough to see this scene are witnessing a real sacrilege that was committed.

It is easy to forget that a movie is not just a fantasy world. For an actor to portray an action, he must do an action, and sometimes the act portrayed and the act committed are one and the same, without simulation. Here, then, are the realities behind the fantasy: There really was a naked woman abusing an image of Mary. That woman had to get up that morning and go to work. She had to undress in front of a group of crew members, perhaps dozens. It may have taken any number of takes to get the final result – sometimes an entire day can be spent making five to ten seconds of a movie. A film director may not know exactly what he wants beforehand, so the actress and crew may be called to improvise and try different things: to put it bluntly, there is no knowing how many different ways this icon of Mary could have been desecrated on the day (or multiple days) spent shooting this scene. Not only the director and actress are implicated in the crime. The set had to be dressed. The actress had to be lit in a specific way. The camera angles had to be painstakingly determined. Each person on set, down to those standing around drinking coffee, had to take this experience home with him. All these things happened in the real world.

Catholics make reparations for sins against God, for offenses against Mary’s Immaculate Heart, and, in the First Saturdays devotion, specifically for sacrileges against her holy images. If an event were scheduled in some American city at which some public act of sacrilege would take place, we would be outraged, and perhaps a Holy Hour of spiritual combat against the evil. Yet what was done on that film set is itself a large-scale collusion in public sacrilege. How, then, can we pay money to see it?

Padre Pio does not seem to be an intentionally subversive film. It offers a sincere if imperfect depiction of the saint, with an actor 100% committed to the role. Indeed, if it were not for the offensive scene, one might complain that the film spends so little time with its titular character, instead being much preoccupied with boring political upheaval and socialist movements in Italy. The result is a somewhat disjointed and piecemeal depiction, explaining so little about Pio’s interior trials that an uneducated viewer might come away thinking Pio was insane. Abel Ferrara could have taken better advantage of what he had in Shia LaBeouf by making a twenty-minute short consisting of Pio saying Mass, with the palpable intensity and love Shia brings to that action.

Ferrara is not a Catholic, so we cannot expect him fully to understand his subject matter. Yet the offensive treatment of Our Lady’s image is all the more puzzling because elsewhere, Ferrara does show some awareness of the reality behind sacred images. In another scene, for instance, Pio prostrates himself before a statue of Mary. When the film cuts away from Pio to the statue, it has been replaced by a real actress, showing that the person being reverenced is the person of Our Lady.

In a sad irony, Padre Pio is bookended with two voiceovers from St. Pio about his desire to make reparation to Jesus’ heart, wounded by man’s sins; yet the film adds to the list of offenses for which Catholics are called to make reparation. Something more than the disinterested film critic necessarily awakens in the Catholic viewer, something with the very name of Pio; it is the gift of piety given by the Holy Spirit, rousing us to defend and console its immaculate Spouse. This is not a mere fictional depiction of irreverence against an image – Mary is really and personally touched by this, and so are all who call her Mother.

This article is a distillation of a longer discussion between Thomas Mirus and James Majewski on Criteria: The Catholic Film Podcast.