Abiquiu

Five. The priest placed a neat stack of five communion hosts in my hand. He said words I could not understand. My line was supposed to be “Amen,” but baffled, all I managed was, “What?”

I’d approached, as one does, as part of a line. A Communion line inching forward over red, dusty ground, under a ceiling of a cloud-streaked New Mexico sky, as one does not often do. Surrounded by crumbling adobe walls, my fellow Catholics rose from folding chairs, waved and embraced as they moved to the front and then back in the centuries old ruin of mission church dedicated to St. Rose of Lima on the side of state highway 84 in Abiquiu.

Seconds before it was my turn, a man edged past, cupping a handful of hosts himself. I wondered about that, then decided he must be official, delegated to take the Bread of Life to the ladies sitting with their canes and umbrellas in the back rows.

Anglos, Indigenous, Hispanic. There were young women dressed in bright tribal garb, bells hung on their belts and knee-high moccasins jingling softly during Mass, there were weathered old men in cowboy hats and boots. The sun was heating up there on that August morning, so yes, umbrellas. Mass was in English, music was Spanish, the Agnus Dei: Latin.

Two men, one older and one younger, stood opposite me in the back, at the wide doorway with no door under no roof on this Saturday morning, this feast of St. Rose of Lima, the mission’s patron. I presumed they were father and son, and later at the feast day celebration, when they were introduced to sing on the stage in the village plaza, I found that this was so. The father, tall and rugged, holding his cowboy hat in his hand, the young man, also tall, seemingly on some road to attempted feminization with soft gestures, long, styled hair, dangling earrings, painted nails and a trans-flag bracelet on his wrist. As we sang, he harmonized effortlessly, beautifully. During Mass, he’d say and also with you, which hadn’t been the script for over ten years now, so it had probably been a while. But here he was, with his father, singing. He was ahead of me in the communion line, and I wondered what he’d do, not judging at all, but of course totally judging. He kept his hands folded. The priest made the sign of the cross over his bowed head.

My turn. I reached out. After the awkwardness, the priest spoke again: Consume them all, please.

I was confused. Confounded, even. The priest had never seen me before, had no idea who I was, and granted, there are probably not too many befuddled 60-ish women in khaki skirts and Teva sandals in the Satanist club, but still. Leaning against the crumbling adobe doorway, doing what I’d been told, digging for reverence, but probably failing, because it was so strange. I prayed a little, felt weird and guilty, and tried to work it out it out.

The mission ruins had history, a spectacular view of the New Mexico landscape, but, it came to me, of course no tabernacle. After Mass, there’d be a procession back to town, the priest carrying a statue of St. Rose, others various holy pictures, a crucifix. There’d be incense, the rosary, and a couple of horses. I’d go sit by a nearby river and journal about the past few days until I judged enough time had passed for them to reach the bottom of the hill, then I’d return, park in the Bode’s General Store lot, and watch the end of the procession. The priest had consecrated more than enough hosts with no way to get them up to the parish on the hill in Abiquiu. So he offloaded, trusting a stranger with so much Jesus.

Well, I thought. There’s a tale to tell. Bloggable, for sure. Followed by what decades on the Internet had taught me would be the response without a doubt: That’s what you get for receiving Communion in the hand.

Can’t argue with that. They’re not wrong. Whoever they are.

I stood in that doorway, took in the expanse of landscape and sky and considered the congregation. As I often do – waiting in line at the store, stopped in traffic, sitting in a theatre - I wondered what strange paths had brought us all here right now. For my part, speaking not metaphorically or poetically, but directly and literally about that exact moment in late August, to this place, it had been a two-and-a-half day drive from Alabama to New Mexico. It was the first voyage from the empty nest, taken to this part of the world because it was warm, I wanted to see the missions, I could catch the opera under the stars in Santa Fe (worst production of Carmen in history, unfortunately – why didn’t I read the reviews? Oh I know – Santa Fe Opera. How could it be bad?), and – yes, I admit it, most importantly: there wasn’t anyone here or even along the way I felt obliged to stop and visit.

But the journey to any place at any time involves more than physical movement, relocation. It’s a wild mix of choice, circumstance and accident that brought us here from Mexico or Vietnam or California or Alabama.

Keep moving. Keep going back. What about the wilder, deeper, and unknowable mess of knotted strands that ended up giving us life at all? In his novel The Passenger, one of Cormac McCarthy’s characters considers that if Adolf Hitler hadn’t existed, he wouldn’t either, since his parents met in a lab in Oak Ridge during World War II. Less ominously: what if your great-great grandfather hadn’t forgotten his hat at the drugstore lunch counter that day and then, upon rushing back to retrieve it, spotted a friendly young lady sitting there? Where would you be then?

Life circumstances, ontological mysteries, what else? What else about this moment, right here? I think I’m standing in the doorway of this old half-a-building right now mostly because when I drove by the other day, noted the ruins and saw the sign in front advertising the fiesta, I believed Jesus would be here. I wanted to stand, sit and kneel here with the other Jesus people: the young and the old, the varied shades of skin, all of us the fruit of a mess of entwined roots and diverging branches.

No, there was no way, once I knew about it, that I would miss the chance to stand in the thickness and layers of this Catholic place with these Catholic people. Including the dead ones.

It’s not morbid to me, it’s just real. The communion of saints gather here with us, and even the here takes us beyond the here and now: this mission was built centuries ago, prayers have been prayed here by thousands, and here we are, praying still, standing on the same dirt, in between the same walls, crumbling, but still standing. It’s amazing to me, that I’m a part of this, that we all are. How could I walk away? From this?

Not that it’s not fraught. To stand in the church the friars and the native peoples built is nourishing. There’s praise and comfort and glory to God, but so much more: exploitation, pain, loss, wrong-headedness, the sins of the oppressors and the suffering of the oppressed. The sins of the world.

And we all sing Agnus Dei.

Georgia O’Keefe’s house and studio looked down on highway 84 a mile or two from the old mission, on the hill in the village, with a magnificent, artist-ready view of the hills to the north. She arrived here after joining up with the bohemian art scene in Tao. She discovered this area, settled at Ghost Ranch for a number of years, then bought the house on the hill in Abiquiu, renovated it and made a studio. Friday nights, she often paid for transportation and tickets for all the village children to go to the movies over in Española.

I toured the house later that day, after Mass, after the river, after the procession, after I’d checked out the present-day parish church off the plaza, dedicated to both St. Thomas the Apostle and St. Rose, after I’d listened to the father and son sing their songs. Today’s tour was a special thing. You would normally have to reserve tickets to see the house far ahead of time, but in honor of the feast, they were opening it up for a donation which would go to the parish.

In the middle of the house, as is often the case in this part of the world, there’s a courtyard. And in one of the walls of the courtyard is a door. A black door.

That, the guide said, is the black door.

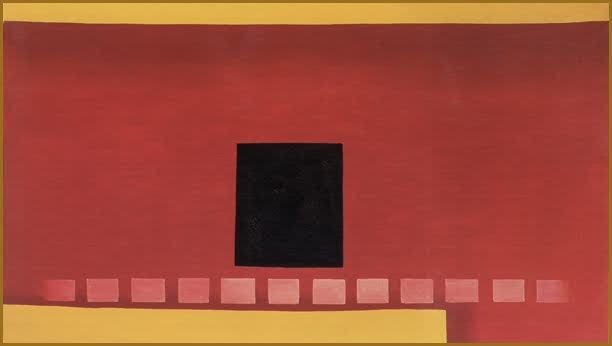

Black Door With Red, by Georgia O’Keefe

The other middle-aged women on the tour said Aaaah and nodded. I nodded, too. The guide explained, for those of us who might have faked our understanding, that O’Keefe had painted or drawn this door over twenty times. And the next day, at the O’Keefe museum in Santa Fe, I saw one of them: Patio Door with Green Leaf.

Why did she return to the door? Why did she say that it was the door, in fact, that compelled her to buy the ruin of a house?

I should have known about the door, I realized later, not only because it’s well, really, really famous, and I imagine myself to be moderately cultured. More importantly, the door had come up in Breaking Bad, which I’ve watched at least three times, in its entirety, over the years. Once again, as I often must do these days, I rationalized my memory failure: I consume so much media. I read so much. You know what Flannery says: Total non-retention has kept my education from being a burden to me. Me and Flannery: practically the same person.

Anyway: Breaking Bad. It’s season 3, the episode is called Abiquiu - of course, although I don’t think any of it actually takes place there - and it opens with a visit to the museum in Santa Fe, and a look at the stark, abstract My Last Door. In the car, an incredulous Jesse peppers his ill-fated artist girlfriend Jane with the question of why O’Keefe painted this stupid door twenty times: Okay, so... the universe took her to a door. She got all obsessed with it and just had to paint it twenty times until it was perfect.

No, Jane corrects him. It wasn’t about making it perfect. Nothing’s perfect. She loved it, Jane says, it was her home. It was about making that feeling last.

O’Keefe, of course, did engage with the same subjects repeatedly: certain features of the landscape, skulls, flowers. The black door. Why? To glance at something once, even to paint it once in a certain moment in time, doesn’t allow us to know the subject well, if at all. We must look again, and then again, from different angles, at different times, in different light. Then, perhaps, after twenty times, we can begin – begin - to grasp what’s in front of us.

So the black door. Looking at the painting the next day, and remember the black door in situ, I understood the attraction, the pull. Would a red or white door have the same effect? I don’t think so. That black door is elemental, invites a second look, even a steady stare, and offers a compelling, if intimidating invitation. We need more than mere curiosity to confront that door. There’s a certain necessity about it.

Georgia O’Keefe’s house with its hypnotic black door was spread out on the hill just a few yards, in one direction, from the parish church with its own open door, and in another direction, a few yards around a bend in the road, from a simple rectangular adobe Penitente Morada – the meeting place for the penitente – laymen dedicated in a special way to charity and yes, penance. It’s a private space, fenced in, doors locked. The O’Keefe house stood tall above highway 84. Take the winding ribbon west a few miles, you end up at Ghost Ranch for more Georgia if you like, drive east, you’re at the ruins of the St. Rose of Lima mission. It once had had a door – probably of heavy wood, perhaps carved with an image of the saint, a rose in her hand and a crown of thorns jammed on her head, as she was wont to do.

But now, no door, only a doorway. Never closed, always open to the tourist driving by, to the jackrabbits and deer, open to the storms and sunrise. For an hour or so, I stood there in that doorway, watching, praying, listening, and consuming far too many Hosts than I deserve, giving scandal to the Franciscan ghosts.

I can’t explain the interweaving of terrors and rescue, of abuse and trust, lies and truth, ugliness and beauty brings any of us to life on this planet, that brought this group to this particular place, or even that brought this place to be.

Of course, each one of us is here because we are loved and God wants us to exist, not just in this place in this moment, but forever. Now, that is love.

But for the rest of it? The why and the how and that what if? I can’t hang a “God’s Plan” banner on it and be content. Some can, but not me. But nor can I let the shadows overwhelm what’s here: the goodness, the mercy, the hope. The Presence.

Above the ragged melody of the communion hymn led by some men up front, confident clear harmony rose beside me. Bells jangled softly behind. The priest cleaned the vessels at the makeshift altar up front, the horses shuffled by the side of the road, firefighters lounged against their long red truck. Under the open sky, in the ancient church with no roof and a floor made of God’s own earth, the doorway stood wide, the place where saints and sinners enter and leave, listen and respond.

It makes sense and then it doesn’t. I understand and then I don’t. I suppose all I can do is just keep returning to that doorway again and again, trying to make sense of what I see.