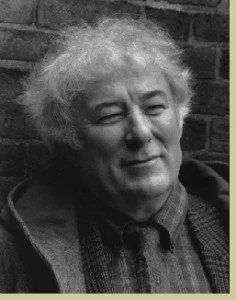

Remembering Seamus Heaney

I'll never know who donated all those Faber and Faber volumes of Seamus Heaney to my high school's library, but I'll always be grateful. At sixteen years old, I was drunk on the possibilities of poetry, but I was just becoming aware of how bewildering and dull contemporary poetry could be. Heaney got past my budding crankiness and clocked me over the head with lines like these:

The wintery haw is burning out of season

All I know is a door into the dark

And in August the barley grew up out of the grave

Elderberry? It is shires dreaming wine

Heaney filled me with courage. You didn't say, reading him, "I didn't know poets were allowed to write like this anymore!" He never asked permission: his superb assurance and sensuous command of English drew from the tradition of poets I loved (Hopkins, Keats) and carried poetry into our own day. Indeed, he took the art of meshing pleasure and language beyond Keats, as no other poet I know has done. His description of eating oysters: "My tongue was a filling estuary, / My palate hung with starlight: / As I tasted the salty Pleiades / Orion dipped his foot into the water." Or more about that elderberry tree: "I love its blooms like saucers brimmed with meal, / Its berries a swart caviar of shot, / A buoyant spawn, a light bruised out of purple." When he applied this sensibility to his famous bog bodies, the preserved remains of ancient human sacrifices, the result was a grim, fermented beauty.

Also exhilarating was the Catholic flavor of his work, a stubborn, latent water table that kept seeping up into whatever cellars of language he might build.* That a man who wrote like this, who believed in mystery, could win a Nobel! That gave heart to teenage me, and still does. Though he came from a background of tribal Northern Irish Catholicism and fell away as a young man, he never seemed to stray too far. Reading his work, you sometimes sense Waugh's "twitch upon the thread" and wish for a miraculous vision. As far as I know, he never formally returned to the Church, though his poetry is haunted to the end by parables, saints, and memories of Latin.

Hearing of his death today knocked the wind out of me. It's the end of an era, for sure.

Let's all pray for him, and that he finds what he translated from St. John of the Cross:

This eternal fountain hides and splashes

within this living bread that is life to us

although it is the night.

*Eerily enough, after I wrote this sentence I came across these lines of his on the internet: "And yet I cannot / disavow words like ‘thanksgiving’ or ‘host’ / or ‘communion bread’. They have an undying / tremor and draw, like well water far down."