Pandemics, Friendship, and Empathetic Imagination

One of the hazards of being both a great writer, and a professor at a university, is that your email is publicly available, allowing fanboys like myself to contact you at will. This is exactly what I did a couple of years ago, having just read one of Jim Shepard’s novels (Project X, I think). I sent him a short note thanking him for writing the book, and asking whether he was currently working on any new projects. He responded that he was working on a novel about a pandemic. Interesting, I thought, a book about zombies; the topic seemed slightly out of character for Mr. Shepard, whose fiction – both short stories and novels – are often intensely researched, highly realistic, historical narratives. Then I googled “pandemic.” Oh, I realized, the book is not about zombies. And then March 2020 happened, and I learned firsthand that pandemics are definitely not about zombies.

After a long wait, I have now read the novel, Phase Six. As I indicated earlier, I am a Jim Shepard fanboy. I’ve loved his novels such as The Book of Aron, about a Jewish boy caught in the midst of the Nazi occupation of Warsaw, and Paper Doll, about the crew of an American WWII B-17 Flying Fortress tasked with a catastrophic mission, as well as short stories like “The Zero Meter Diving Team,” about three brothers involved in the Chernobyl catastrophe. Come to think of it, Mr. Shepard writes a lot about catastrophes, and Phase Six is no exception.

One of the wonderful things about Phase Six is both its closeness to the past year, but also its distance. This is not a novel about COVID-19. But in reading about the lives impacted by a pandemic in Phase Six, from 11-year-old Aleq, who unwittingly unleashes the outbreak in a tiny settlement in Greenland by trespassing at a mining site that has exposed thawing permafrost, to Jeannine, an epidemiologist first dispatched by the CDC to investigate the outbreak and then dispatched to a remote, high-security facility in Montana to gather information from Aleq, one hopes that one’s own empathetic imagination might increase. That as a reader experiences individual suffering and guilt and fear and uncertainty, but also tenderness and mercy and heroism and bigness-of-spirit, one’s own capacity to love during the current pandemic might grow. What perhaps struck me most about Phase Six is that even in the midst of a worldwide catastrophe, where every government, and institution, and agency must get involved, the real drama of life is still the drama of individual human souls. The drama of individual choices; the drama of family loss and family love; the drama of finding connection and purpose and friendship in a sometimes-brutal world. And ultimately, the drama of discerning and attempting to do God’s will.

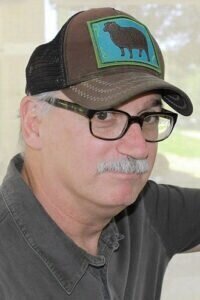

Mr. Shepard graciously agreed to a conversation about his new book, empathetic imagination, friendship, and a host of other topics. I hope you enjoy it.

I want to begin asking you about your latest novel, Phase Six. You are infamous for the intense amount of research you conduct for your fiction, both for your novels and your short stories. For example, the acknowledgements page of Phase Six takes up four pages. Do you remember what sparked your interest in writing about a worldwide pandemic, pre-COVID-19? Do you feel in some way vindicated and prophetic, or a little unnerved by your own clairvoyance?

JS: Four years ago I was jolted by a story out of Siberia of a 12 year-old boy killed by anthrax, with 20 others infected. The Russians were panicked — anthrax hadn’t been seen there in over 75 years — and investigators were floored to discover that long-dormant spores of the bacteria frozen in a reindeer carcass had rejuvenated themselves to infect the boy. I knew that the permafrost bordering the Arctic Ocean had long been stable but with the Arctic now warming so much faster than the rest of the globe, all of that biological material full of pathogens was re-emerging. And both Russia and Greenland had announced extensive plans to mine all across their northern extremities, meaning millions of tons of permafrost excavated and mountains of pathogens thawing alongside new mining communities. And those miners from all over the world periodically flying home. So this seemed to me, in terms of disaster, a matter of when and not if, and I thought: well, since I’m going to be obsessively unable to stop learning about all of this anyway, maybe I should write about it. As for my clairvoyance, as I’ve noted elsewhere, the experience of watching a matrix of catastrophe unfold right after you’ve worked as comprehensively as you could to try to imagine it has a surreal edge to it, like an echo of deja vu, leavened with a superstitious sense on the one hand that maybe your imagination should have left well enough alone, and a chastened sense on the other that Cassandras are a dime a dozen, and by definition ignored. But even so, the entire project of literature may be about trying to prevent ourselves from repeating our mistakes.

Let’s jump to the final paragraph of Phase Six. This passage had me spellbound. It is a summary of a minister’s sermon about a big storm that had caused some destruction in town. The sermon pre-dates the pandemic, but is clearly apropos. Here is the excerpt:

He said he wondered why they didn’t believe they’d been commanded by the shaking of the supposedly solid rock to heed the angry voice of God. He asked if they thought their God would tear up their houses from their foundations and bury them in the ruins for no reason. He asked if it had occurred to them that they might receive their summons to step into eternity without any warning. He said that some storms were so terrible that it was as if God had decided to punish the sins of many years in a single day. He warned that a storm like that was a challenge to their intelligence that they must accept. And he said that in a place called Lisbon, after one such storm, the king had cried out that he didn’t know what he should do next, and that one of his ministers had finally answered that before they could make whatever other changes they needed to make, they first had to bury the dead, and feed the living.

This passage beautifully evokes the mystery of the power and sovereignty of God, but also the challenge of theodicy. Would you agree that these final lines are a lens through which to read the whole novel? Are you also trying to say something about our present American moment, one that seems increasingly obsessed with D.C. and politics and people “out there,” but perhaps forgets about the neighbor next door, and about what the Church would call the corporal works of mercy?

JS: Yes. The passage is inspired by some of the famous and not-so-famous responses to the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, and of course those issues are exactly what the thinkers of the time had to confront. My novel certainly isn’t blind to the devastation our politics can wreak on our planet and our individual lives, but it’s also very much about that capacity each of us has to be each other’s rescue.

I read in a Ron Hansen interview where he said that you considered yourself a Catholic novelist, but that your Catholicism does not come out as obviously as does Hansen’s in his own fiction. Do you agree with those statements? Do you consider yourself a “Catholic novelist,” or novelist who happens to be Catholic, or who was raised Catholic, or who is tormented by Catholicism, etc. Have you seen Catholicism and faith shaping you as a writer?

JS: I do agree with Ron’s characterization of me in that case: given both my background and my worldview, I would consider myself a Catholic novelist. Which is not to claim either that I’m devout or that I’m unappalled by much of the Church’s history.

In his recent book The Decline of the Novel, Joseph Bottum argues that the novel is primarily a Protestant art form that focuses on “the salvation and sanctification of the individual soul.” Certainly your own fiction is concerned with strong individual characters and the possibility for grace and salvation (a child victim of the Holocaust; a tormented German silent-movie director; a single-mother who tries to cover up a hit-and-run accident). But it seems to me that at the heart of your fiction is also relationships. Family dynamics. Father-son relationships. Doomed friendships. The possibility of self-giving love. At the heart of the New Testament is not simply individual salvation, but the concept of the Kingdom of God (especially in Paul's writing); the notion that somehow my salvation is bound up with the salvation of the community. Your fiction seems to me to be about more than just individual grace and salvation. How would you respond to Bottum? What does the Kingdom of God and community mean to your own fiction?

JS: I suppose I would amend Bottum’s formulation to add that the salvation of the individual soul for me always involves the individual’s relation to others. Without that concrete relation, notions like goodness and grace, it seems to me, remain unhelpfully abstract.

Friendship also seems so vital to your fiction. For instance, the friendship between Aleq and Malik, and also between Danice and Jeannine in Phase Six. But also in your other novels, like Nosferatu and The Book of Aron, and the tragic friendship between school shooters in Project X. You write about friendship in complex ways - the ways that a friend might lead us toward destruction (Project X). Or how a friend might betray or abandon us (Nosferatu). Could you talk about the power of friendship? What is it about friendship that keeps you coming back to the theme?

JS: For me the project of literature is also in crucial ways about the size of that gap that we perceive between who we wish to be and who we all too frequently are. And friendship feels to me an opportunity to enact versions of both that shortfall and those rare achievements in closing the gap.

Speaking of friendship, as a reader of both Ron Hansen and you, I’ve long been encouraged by your friendship. You often credit one another in your books, have collaborated on projects, and mention one another in interviews. What do you think is the role of literary friendship in a writer’s life?

JS: The sorts of sustenance that you might expect. Writing is an odd and solitary way of connecting with the world, and so finding something like an ideal reader is a marvelous and important thing. We also now have our whole histories, of a sort, in our heads, and so have a perspective that other readers and friends might not have. Ron and I are also frequently amused and pleased by how different we are: a notion that is perhaps additionally encouraging as well.

One of the things that I love about your fiction – both in the novels and short stories - is that they often deal with adolescent boys. I must admit, I am a sucker for coming-of-age boy stories. But you subvert that genre, working with deeply flawed, wounded souls. These boys are often fatherless or do not have a good relationship with their fathers. Unlike in the classic coming-of-age story, where the boy goes through some hardship and comes out a better, stronger, “man” in the end, the fate of your young males is often in doubt. One thinks of Aron, who is likely bound for the gas chamber. Or Edwin Hanratty, the would-be-school shooter who perhaps is saved by the fact he didn’t actually pull the trigger, but hates himself for failing to do it. Or Aleq, who appears destined to live as a bubble boy, with the knowledge that literally everyone he knew and loved has died. Why do you keep coming back to adolescent males as a subject? What do you think about the possibility of redemption (both on a human, but also divine plane) for these boys you write about?

JS: I’ve always been interested in the child’s radical vulnerability, for one thing. That difficulty that children have in articulating the sophistication of their perceptions, for another: a difficulty with which most writers can sympathize. And I’m drawn to the intensity of a child’s (or especially an adolescent’s) world view: how apocalyptically they can see things. I’ve also always been moved by the demands the more heartless aspects of our societies routinely dump upon children.

I want to ask you about portraying goodness and sanctity. You as much as any contemporary fiction writer plumb the depths of evil, sin, and suffering. When I read Project X, it reminded me of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, really engaging with a depraved mind and broken soul. Of course, Dostoevsky also wrote about sanctity and goodness; both with Prince Myshkin (less successfully), but also with Alyosha (very successfully). In The Book of Aron, I also think you pull off one of the most beautiful and believable depictions of holiness in the character of Janusz Korczak, the renowned Polish doctor who runs a Jewish orphanage. One senses the cost of his love, and also his own battle with despair and exhaustion. Could you discuss how you approach writing about goodness and virtue and sanctity? Do you think as a writer you have some obligation to show both sin and suffering, but also goodness and at least the possibility for redemption?

JS: Good question. It’s not too hard to figure out why goodness is so hard to write about, since it tends to obliterate complexity as well as the kind of conflict on which literary fiction runs. In the case of Korczak, my way in was imagining a perceiving lens in the form of my narrator who A) wasn’t particularly focused on Korczak, and then B) approached him with skepticism. In some ways that allowed me to more easily access the agonized and hopelessly compromised aspects of Korczak’s position, even given what we’d have to call his incontestable saintliness.

I’ve often been struck by the phrase “empathetic imagination,” a concept that seems near and dear to your fiction. Could you discuss what an empathetic imagination means to you? I’m particularly interested in what the phrase ought to mean to a Catholic fiction writer who comes to their fiction from a particular Tradition and set of beliefs? How can one develop a stronger empathetic imagination?

JS: If, as I noted above, the project of literature in crucial ways is about the size of that gap that we perceive between who we wish to be and who we all too frequently are, one of the central ways we shrink that gap is by working more fully to imagine the other, to get outside the prison of our own agendas. I think it was Allen Gurganus who remarked that the favor of trying to imagine one another’s interiors might be the most profound thing we can do for one another, and one of the least profound things, as well. I do think that the entire project of the arts is about the development of the empathetic imagination: the development of that saving ability to really imagine ourselves in someone else’s position.

I consider you one of the living deans of American letters. If you could give some advice to young fiction writers in the current and coming generation(s), what would it be?

JS: One of the living deans! Now I feel both honored and old. On the one hand, I would encourage them, for all of their seriousness and ambition, to stay in contact with the spirit of play: with that passion that we all access in childhood that enables us to try what we might not try, to find joy in the process of what we’re doing, and to not find failure at something we’ve attempted to be devastating or defining. And on the other hand, I would wish them well as they head into a world in which reading itself – especially in any sustained and absorbed way – is becoming less and less common, and less and less valued.

Bonus question: Walker Percy once gave an interview to himself of questions interviewers never asked him. Is there a question you have never been asked, that you now wish to answer?

JS: Oh, maybe: what constellation of minor dysfunctions would have to come together to possess someone to become a lifelong Minnesota Vikings fan?

Jeffrey Wald writes from the Twin Cities.