Resurrection and the Everlasting Image

I don’t like that word, “finish.” When something is finished, that means it’s dead, doesn’t it? I believe in everlastingness. I never finish a painting—I just stop working on it for a while.

— Arshile Gorky

Over time, the couple had developed a fondness for this eccentric character, whose sad eyes and lanky frame appeared regularly in the doorway of their cafe, and for whom they generously provided nourishment. He was one of them, just not as lucky. So, they felt sympathy for him, accepting the strange images he scrawled on whatever was at hand as payment for his meals. Between themselves, they called him “Crazy Arshile” in Armenian, and politely accepted his drawings, tossing them away once he was out of sight. Years later, after the art establishment had proclaimed the importance of this man and his work had become famous, they were overcome by regret at having done this. Like Saul before the scales dropped from his eyes, they were unable to see the value of the gifts they had received. The drawings were lost to history.

Similarly lost are the details of the story. Passed around in Armenian families much like my own, this oral history has the shape of a myth. Those of us who have remembered and retold it have undoubtedly distorted it along the way. But I’ve always found the tale as intimate as it is incomplete, like the yellowing image of a distant relative in an old photograph. Its hazy features continue to have a hold over me.

Crazy Arshile was himself caught in the spell of such an image.

A Past Recollected

It was during the 1920s, and having recently arrived in America, Vosdanik Manoog Adoian was living with a father he barely knew. In the home they now shared, he discovered the photograph taken in the city of Van, before he and his sister had fled Armenia. It had been made a few years before the genocide, and sent to his father Sedrak Adoian, who had emigrated to the United States to avoid a military draft. It was hoped that the photo would help motivate him to provide financial support for his estranged wife and their four children. This image would eventually play a pivotal role in Vosdanik’s life, and after he had reinvented himself as the artist Arshile Gorky, it would serve as a vehicle of personal regeneration.

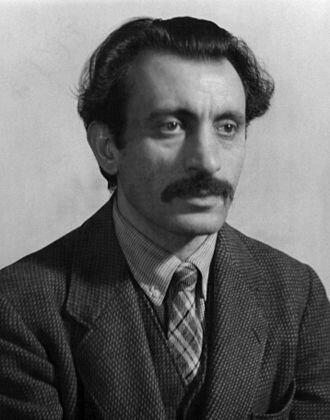

Arshile Gorky

Taken in a photographer’s studio in 1912, the black-and-white image presents Gorky standing next to his seated mother, as if he were a diminutive husband. His mother’s name was Shushan der Marderosian, a peasant of noble lineage. The two are posed in a stiff, frontal manner, their faces filled with a mixture of desperation and hope. Though only eight, Gorky seems older in a long Chesterfield coat, as he holds a delicate sprig of flowers in his hand and gazes intently at us. His face is like that of a ghost, teetering on the edge of the visible, while his mother’s is in sharp contrast. Her stare seems both introspective and fearful. Her face is framed by a kerchief. She wears a jacket covered by a dress, cut like a smock. Her thick hands, evidence of a life of labor, rest on her thighs. Mother and child are posed before a meager, painted backdrop. This photo served as an icon for Gorky, an object of meditation that would occupy his creative imagination for many years.

In March of 1919, the young Vosdanik watched his mother starve to death in his arms. She had become one of countless victims of the Armenian genocide (1914-1923), during which the Ottoman Turks attempted to displace or exterminate the Armenians living within their empire. Years later, Gorky would return to the old photograph, and working from it, he would recreate the childhood, mother, and homeland he had lost. For the artist, love would conquer death through the transformative power of the creative act.

Rebirth in the New World

Gorky produced two versions of The Artist and His Mother (1926-1942), along with many preparatory sketches and studies on the theme. The one pictured here belongs to the Whitney Museum in New York. It is significant that he was occupied with the image for so long, considering that he only lived to his forties, committing suicide after a series of personal tragedies. He adhered closely to the photograph, and despite countless variations, each of his drawings and paintings maintained its primary elements. Gorky would deconstruct the image into constituent parts and explore it in depth. He would extensively rework both paintings over many years, never fully arriving at a conclusion. What was left was an evocation of personal and national tragedy in a visual language that was equally figurative and abstract.

The Artist and His Mother

Having studied and developed a sophisticated understanding of the European avant-garde, when Gorky painted loss and mourning it was through a modern sensibility. And by reprocessing and reordering the image in these melancholic double-portraits, he memorialized his past and rescued it from death. He did this by approaching portraiture in a new way, creating an image that was mutable. The process of change and continual reworking is visible on its surface, along with a sense of uncertainty and instability. The painting is replete with elements that refuse to cohere or to resolve themselves in a comfortable way. Through painting, Gorky’s suffering became a path to salvation, as woundedness and death were transformed into everlastingness.

Resurrection does not only apply to the body of Jesus. It is the cosmic pattern of life. In every death there is a transformation, and when suffering leads us to God we are born anew, just as it was with Jesus after his crucifixion. As an eternal process, there is no separation between incarnation, death, and renewal. Jesus’s resurrection as Christ is the model for the redemption of all things in the universal cycle, in which death is never the end. A part of Gorky died in the death marches, to be reborn as a great modern painter. The same pattern applies to the Armenian people, who, as a result of the atrocities, would become scattered throughout the world, forced to reinvent themselves and build new communities in adopted lands.

Western Christianity is focused on the individual resurrection of Jesus, but representations in the Eastern Church depict a universal outlook. Eastern icons, including those from Armenia, show Jesus pulling others out of death, so that resurrection is seen as apokatastasis: a restoration of all creation.

Gorky was born near the rugged shores of Lake Van, in the province of Vaspurakan. Armenians had lived here since Urartian times, but the region was seized by the Ottoman Turks during the genocide, part of their brutal confiscation of large parts of historical Armenia. Atop dry, stone-covered cliffs dotted by wildflowers, on the island of Aghtamar in Lake Van, sits the Cathedral of the Holy Cross. A silent witness to both lilting hymns and the tumult of invading armies, this Armenian Apostolic cathedral was completed in the early tenth century. It is renowned for the extensive array of bas-reliefs which adorn its external walls, featuring a variety of religious figures and motifs. The ambitious scale of its ornamentation makes the cathedral unique in the history of Armenian architecture. Gorky was raised in its shadow. Fully appreciating his achievement requires a knowledge of how such ancient sources from the East informed his modern approach to painting.

“Isola di Akdamar nel Lago Van: la chiesa della Santa Croce – Island of Akdamar in the lake Van: church of the Holy Cross” by mariurupe is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The outer walls of the cathedral are encircled by four sets of friezes, which feature a sequence of figures and creatures both religious and mythical. Christian saints are among the sixty-one specific individuals carved into the stone, many originally painted and with eyes of glass or semi-precious stone. These are thought to include John the Baptist, along with the two apostles, Thaddeus and Bartholomew, who are said to have brought Christianity to Armenia in the 1st century. Also featured are important figures from the Armenian church and ancestral members of the Artzruni dynasty, the patrons of the cathedral and the first Christian feudal family in Armenia. The stylistic resemblance between these reliefs and Gorky’s two paintings is telling.

Like much traditional Armenian art, including the frescoes within the cathedral, these reliefs are frontal and strangely proportioned. Faces are oval and eyes are large, set into deep sockets. The figures are flat, the volumes of their garments implied through line. They convey the holy in the expressive and symbolic language of Medieval portraiture. Gorky synthesized this vocabulary with the concerns of modern painting, infusing the deep religious faith of his people into The Artist and His Mother. Reinventing the tradition that sustained him in a contemporary language, Gorky redeemed his suffering in an image that bears the timeless quality found in the spiritual art of his ancestors.

Continuing the stylistic conventions of Aghtamar’s cathedral, Gorky’s figures are physically disconnected from one another. Unlike in the photograph, the boy stands behind his mother, feet turned away, while a gap separates them. They share colors, but their hands, smudged and obscured, suggest that they cannot grasp or hold one another. There is a certain violence in this gesture, particularly in the erasure of the mother’s hands. Gorky’s painting also conjures up the past in the abstract shapes that define the figures. While distinctly modern in style, the flat planes of color hark back to the ancient carvings and the period's memorial portraiture more generally.

The references continue in the spatial organization of the painting. Echoing the arrangement of the reliefs, which float in open friezes, the space of the painting is ambiguous. The wall behind the figures is broken, and it’s position unclear. A dark brown square, framing the mother’s head, resembles a window but provides no view. Its stubborn opacity is like an erasure of the landscape from the lives of the Armenian people.

Both heads seem derived from Aghtamar. Greatly simplified, they feature deep-set eyes and elliptical faces that are more mask than flesh. The boy’s hair is as crisp and neat as that of Aghtamar’s sculpted saints. Though clearly defined, these heads seem separate from the loosely painted bodies to which they’ve been joined. Expressed in broad passages of warm, earthy color and devoid of line, the bodies possess a soft, ethereal quality. Their forms seem both assertive and dematerialized at the same time. But the heart of the painting beats through the image of the artist’s mother. A monumental influence on the young Gorky, she was the first to introduce him to art and the primary source of his national identity. Raising his mother from the dead through his art, Gorky gave her new life in the eternal form of an Armenian icon.

The mother’s image reflects the timeless quality she possessed for Gorky. Her distant gaze seems eternal, as though sculpted in stone, unlike her son, whose downcast eyes suggest emotion. Rigid and fixed in space, she is almost a ghost. White paint has washed her apron clean of the elaborate patterning found in the photograph. Her classical face is expressionless, and remote as an ancient statue. It was drawn meticulously and in phases during the period that Gorky was working on this theme, indicating its importance to the artist. Her dress, rendered with vigorous strokes of the brush, falls off the bottom of the picture. It pushes her forward, away from her son and into our space. Her headscarf is like a halo, and she appears like the inhabitant of some eternal realm. In the version owned by the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., her face is bloodless, having taken on an ivory smoothness through the continual scraping and polishing of many layers of paint. Her icy complexion contrasts in that painting with her son’s, whose darkened flesh tones Gorky has built up through a continuous layering of color.

Uprising

My people are deeply rooted in faith. In 301 AD Armenia became the first nation to adopt Christianity as a state religion. Surrounded by powerful neighbors, our rich history in every era has been characterized by the cycles of death and rebirth. But the twentieth century brought unthinkable atrocities as more than 1.5 million Armenians perished at the hands of the Ottoman Turks. Driven into the desert to perish, they managed not only to survive, but to thrive. They resurrected themselves and passed on a national consciousness to their offspring, who like me, were born far from the ancestral homeland. Wherever they went they would build their churches, safeguarding tradition to the current day.

In 2019, after many failed attempts over the decades, Congress officially recognized the Armenian genocide in a landmark resolution, making the United States one of twenty-nine other countries around the world that have officially condemned Turkey’s acts. I was jubilant to hear the news, which came suddenly, as though dropped from the sky. Yet the national trauma remains unresolved, since the Turkish government continues to deny the genocide. Turkey’s attempts at an erasure of the historical record are yet another form of violence directed against the Armenian people.

The recent eruption of conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh resulted in the ceding of the region to Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey. A part of historical Armenia since the 2nd century BC, Nagorno-Karabakh was reclaimed from Azerbaijan after the fall of the Soviet Union. Overrun by Azeri forces who were supported by mercenaries in late 2020, its mostly Armenian population suffered another tragic loss.

Born of the suffering produced by war, torture, hunger and loss, The Artist and His Mother is a work that represents the indomitable spirit of the Armenian people, but also redemption. In affirming ongoing life, it destroys death, as Christ does in his resurrection. Art can give material form to the universal pattern where everything is transformed through love: family, home, and homeland. And just as Jesus appeared before the disciples bearing signs of his crucifixion, Gorky’s painting resurrected a deeply wounded past. It’s expressive form, imbued with longing and anchored in a vision of resurrection, makes it a modern icon in the Eastern tradition of universal restoration.

Every year on April 24th, Armenians and their supporters around the world commemorate the Armenian genocide. But as we collectively mourn our family history, we must also resurrect the spirit of those lost. We do this through the actions we take today that support nationhood, in the Republic of Armenia and in all the other Armenia’s we have created. Resurrection is always and everywhere available.

In a well-known passage, the renowned Armenian-American playwright William Saroyan spoke about resurrection in the context of our people’s historical struggle:

I should like to see any power of the world destroy this race, this small tribe of unimportant people, whose wars have all been fought and lost, whose structures have crumbled, literature is unread, music is unheard, and prayers are no more answered. Go ahead, destroy Armenia. See if you can do it. Send them into the desert without bread or water. Burn their homes and churches. Then see if they will not laugh, sing and pray again. For when two of them meet anywhere in the world, see if they will not create a New Armenia.

We must also stand in solidarity with oppressed nations today to cry out against man’s inhumanity to man. Following the Armenian genocide, attempts at erasure of a people have continued in countries around the world, from the Holocaust to the Middle East and Africa. Every call for justice, including the Armenian demand for recognition and reparations from Turkey, can be modeled on Christ's work. The Holy Spirit inspires us through our collective memory to actively engage in the co-creation of a more just world. Just as Arshile Gorky restored his mother and gave her everlasting life on canvas, so must we actively work to keep our hearts open to God’s message. In the season of Lent, the temptation of Jesus in the Judaean desert, and the death marches of Armenians in the Syrian desert are linked. In the face of great suffering, it is the mind of Christ that transforms death into life.