New Forms, Hot Priests

Check out the first post in this series: New Forms, New Popes.

Major spoilers for Fleabag Season Two below.

Back in January, the release of The New Pope (a sequel series to 2016’s The Young Pope) was, for all its flaws, like a kicked-open window in a house otherwise shut up for the winter. Think art-house quality brought to the Vatican. Complex portrayals of the clergy who work there. Cinematography that actually lives up to the grandeur of St. Peter’s. Proverbial fresh air and all that. And it makes for a weird viewing experience, especially given that most papal dramas tend to either whitewash or sensationalize the papacy.

That show got its own post here on the blog: New Forms, New Popes – you can follow the link for more on that show’s hits and misses.

The series generally got me wondering more about questions of representation, particularly with how religious traditions get treated on screen. Catholicism doesn’t have the greatest track record of getting nuanced TV treatments – like the Vatican, it’s a common target for getting watered-down or villainized.

The clergy are often the first victims of this dynamic. They can’t really escape it – they’re walking symbols of the faith and what it represents. And for many, what cassocks or habits represent are the sins of their wearers. Which is why it’s refreshing to stumble across depictions of consecrated life that are generous, multifaceted and entirely contemporary. More of that, please.

That’s not to say though that The New Pope’s treatment of the clergy got it right. For every accurate moment the series pulled off, there was one that got played up for television. And that made me think about what other recent shows have been better at exploring the complexities of consecrated life. And there was one entry from 2019 that not only fits the bill, but even got bucketloads of critical acclaim from demographics not typically invested in stories of faith.

More on that in a minute, though. There’s a woman you need to meet first.

Meet Fleabag

The world was introduced in 2013 to an unnamed woman, informally known as Fleabag, in creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s one-woman play of the same name. The production started as a Fringe Festival favourite before being adapted into an BBC miniseries in 2016 (featuring Waller-Bridge in the main role), with a second and supposedly final season put out last year.

Reading the synopsis doesn’t make you think the series would gain so much traction: a fairly privileged, middle-class woman navigates life and love in London. What ended up turning heads was the main character herself.

Fleabag’s flirty, hilarious, put-together exterior fools most of us – that is, until evidence builds up that it’s all a big defense mechanism concealing an avoidant personality with a history of trauma. She uses humour and sex to avoid facing herself. Her encounters with friends, family and lovers are played for the kind of laugh that makes you think of people you’ve loved and hurt. This is the kind of subject matter that might seem off-putting for some Dappled Things readers, but there’s a constant invitation to look under the surface.

As I get it, it’s her relentless messiness that’s made her such an icon for millennials entering their late 20’s and mid-30’s. Fleabag is exuberant and can’t help falling apart. She steadies herself on the edge of snickering or tears, telling jokes that leave a mark. This is a woman who finds it too difficult to express how she feels and who’s pain evokes solidarity even as she lights up a room.

Most of her relationships come down to performance. She performs to the people around her, and she shares her thoughts with the camera to make the audience feel like we’re in on the joke. By the end of the first season, though, the truth comes out and it becomes clear that she’s been performing for us the whole time too. That’s as much as I can say without spoiling the thing.

And it really is that messiness that makes the whole affair stunning, shored up by a powerful central performance. Every look and gesture adds up to a character trying to navigate modern life but tripping up over the potholes in the tidy, sometimes kitschily progressive world we’re told to share together.

But Fleabag is never tidy, and she’s too raw to be kitschy. She knows what it means to respect herself and other people, but doesn’t live up to her own standards. She preaches self-actualization but readies a deflating joke the next time she reaches for a cigarette. She acknowledges feminism but questions whether she’d be as interested if she had bigger breasts.

She is, as you imagine, a riot.

Waller-Bridge’s performance feels so authentic, so prankish, that it’s hard to imagine Fleabag getting whitewashed or cancelled for any of the stray, unorthodox bits of humanity that rise to the surface. She manages to be something that only very good art achieves: a paradox that reveals a miniature but entirely-formed world. Fleabag goes to lengths to prove how functional she is, but she can’t entirely fit into what our modern, rather polarized cultural camps might promote as healthy womanhood.

And that gives more leeway than usual to play with contemporary social values. Sex is portrayed as liberating, but also as how Fleabag medicates her issues. Compulsively. Art is an expression of freedom and also (through the role of the Godmother, played deliciously by The Crown’s Olivia Coleman) a way for bullies to promote themselves. Relationships are a safe harbour and a yardstick for comparative success. Fashionable, absurd platitudes are held up while also making space for people who don’t entirely fit that mold.

As with anything, some values are promoted more than others (this is a high-concept, culturally liberal series after all), but we feel less like having been taught a lesson than having spent time with a confused and precious friend.

Which made it interesting when season two (the first season was originally planned to be a miniseries, without continuations) announced a major new role: a Catholic pastor.

Hot Priest

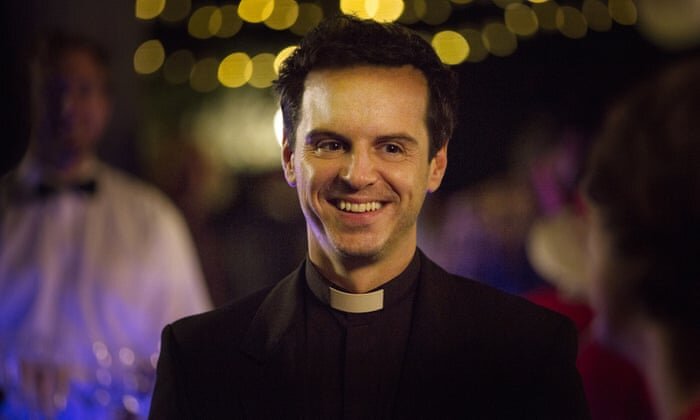

Like many of the characters in Fleabag, the priest (played by Sherlock’s Andrew Scott) doesn’t have a name – he’s only listed in the credits as “Priest.” Though that didn’t stop Twitter from transforming him into the Hot Priest, one of the 2019’s less forgettable memes.

He’s introduced at a family dinner, just over a year after the events of the first season. The family celebrates Fleabag’s father’s upcoming marriage to the Godmother, but everyone’s walking on eggshells. The small talk is tense. Fleabag, coming off a year of trying to put herself together (her latest way of avoiding emotion), tries to figure out if there’s anything left of her and her sister’s relationship. The Godmother talks about her latest art show and parades the Priest like he’s an accessory. “I must say,” she says, “I think there’s something rather chic about having a real priest at a wedding.”

Fleabag and the Priest make an unexpected connection that night, sparking the season’s main plot: her slow realization that she’s falling for a man who’s embraced a call to celibacy.

Since Fleabag’s approach to sex is entirely different, she’s both frustrated and intrigued. Unlike many clergymen who show up in Peak TV (The New Pope included) Andrew Scott’s priest is neither a sly hypocrite nor a victim of his beliefs. He responds on a human level to his connection with Fleabag and is able to communicate just what his vocation means. The Priest is exuberant, playful (“sometimes I worry I’m only in it for the outfits,” he quips) and asserts the need for meaningful platonic connection in lieu of a sexual affair.

The connection is real, though, and neither of them know what exactly to do with it. They can’t help wanting to be around the other and hesitantly explore what their boundaries should be. After having a drink in his backyard, the Priest comes out and says he won’t sleep with her. Fleabag, slightly off-balance, returns another day to say that priests don’t explode if they happen to have sex.

“I read that somewhere,” she affirms.

He laughs and gives her something else to read.

Describing their connection as entirely healthy, though, would be a lie. She wants to get closer. She’s torn between wanting to sleep with him and knowing that would ruin their friendship. Fleabag knows there’s something deeply unsustainable about all this, but she hasn’t felt this unlonely in a while and can’t help remaining in his orbit.

On his side, even though he’s blunt about what he can or cannot do, he is keenly aware of the warmth seeping up through the floorboards. He responds, but trods carefully.

There have been a lot of interesting responses from Catholic outlets about the Priest’s behaviour – critics have claimed his friendship with Fleabag is a near occasion of sin or that his duty requires him to treat her as a vulnerable person rather than a friend. Others have pointed to the friendship as sympathetic and a door into understanding what the clergy’s oft-overlooked human needs look like.

The show certainly provides a great deal of sympathy for the Priest. His celibacy prompts bewildered laughs but never becomes the butt of the joke. His vows aren’t treated like a backward practice to be defended half-heartedly until a climactic moment of liberation – they’re treated with respect and dignity even though Fleabag chafes and tries to understand its restrictions.

That’s not to say the Priest is idealised. Far from it: he’s broken and cagey. His self-awareness comes with the inevitable combo of baggage and compulsion (he seems to use alcohol as a defense mechanism) along with, maybe, a sense of failure for not being the saint that no one is capable of being without tremendous amounts of grace.

What makes their back and forth interesting is how grace, God and dogma are real things to be contended with, which is not usual for this kind of show. Fleabag, a 21st century atheist, is forced to navigate theology as part of the equation – if, that is, she does intend on keeping up a friendship with the strange, shifty, adorable man she’s met.

But it’s obvious that none of this is sustainable – their friendship is punctuated by the tension of mutual attraction, and both of them have very different ideas of what they want. Fleabag is learning how to explore connections without sex, and any relationship where she feels less of a need to perform is already a success. The Priest wonders if there’s a way to get over the initial spark and maintain a connection that feeds him in a way that leaves him less lonely. He is the only other character on the show who notices when Fleabag speaks to the camera, implying a meta-level connection that can’t be dismissed outright.

The season starts off with a classic will they/won’t they vibe, with the “it” in question being falling into bed. But the stakes are actually much higher: can they be vulnerable in any real, sustainable sense without the whole thing falling apart?

As usually happens, things escalate without much prompting. Sensing she has something to get off her chest, the Priest suggests the confessional and describes the psychological relief it can bring, even if someone’s not entirely on board with the sacraments. She humours him, steps inside and shocks herself by actually uncorking her heart:

“I want someone to tell me what to wear in the morning. I want someone to tell me what to wear EVERY morning. I want someone to tell me what to eat. What to like, what to hate, what to rage about, what to listen to, what band to like, what to buy tickets for, what to joke about, what not to joke about. I want someone to tell me what to believe in, who to vote for, who to love and how to tell them.

“I just think I want someone to tell me how to live my life, Father, because so far I think I’ve been getting it wrong — and I know that’s why people want people like you in their lives, because you just tell them how to do it. You just tell them what to do and what they’ll get out at the end of it, and even though I don’t believe your bullshit, and I know that scientifically nothing I do makes any difference in the end anyway, I’m still scared. Why am I still scared? So just tell me what to do. Just f***ing tell me what to do, Father.”

The scene is electrifying, unnerving. She’s not what she’s supposed to be – she doesn’t live up to her culture’s ideas of independence or personhood, she’s stuck where she is and she generates entire audiences in her head to feel less isolated and none of it works. And she’s done, none of this is sustainable. All it’s gotten her is a stable life and some success at the cost of being strung up and constantly on guard against the destructive ways she medicates herself and it’s only led her to a latticed wooden box where she pours everything out to a man she can never have in the way she thinks she wants.

That’s when I sat up straight in my seat. In a moment, the show resembled less an intelligent, unusually generous liberal comedy and more a New York high-wire act strung up between skyscrapers. I may have covered my mouth. I may have kept asking myself: is this really going there? Am I actually seeing this?

I thought of shows like The New Pope, where some respect is afforded to the clergy but, really, the directors portray them as sympathetic to the degree that they’ll eventually get with the program and realize that liberal humanist values are intuitively correct and anyone who’s honest with themselves will get there eventually and admit their lifestyles are untenable (or, at the very least, somewhat embarrassing).

Fleabag, on the other hand, allows its protagonists to be broken and attracted to each other and still actually have irreconcilable, frustrating, metaphysical belief systems that won’t just resolve themselves. It allows Fleabag to be relatively woke and still respect consecrated life. It shows the Priest’s commitment to his vows and that he has a pulse.

Needless to say, I invested rather quickly in their back-and-forth, in the possibility that they might find a way to make things work and not explode in a whiff of drama and unmet human need. And Waller-Bridge, as a writer, is so attuned to her character’s lives that it seems possible she might find a plausible way through. A plausible way for people to be mature, human adults with actual needs who still prioritize the kind of emotional maturity necessary to not have everything descend into pyres of hurt and compulsion.

And I’m obviously not neutral here. I’m invested in stories that show how people coming from vastly different backgrounds might form meaningful connections. I’m big on that. I’m deeply impressed when secular shows treat people’s faith as something more than an obstacle to human flourishing. I’m big on that too.

On a personal level, as a queer Catholic, I’m particularly floored by stories that explore these kinds of tensions. I’m invested in Fleabag’s understanding that chastity can actually be important to someone. I’m overwhelmed by the Priest’s honesty, his flaws, in his ability to imagine a chaste connection in which the heart is still very much a factor, in which something rich and rare is brought into one’s life, in which a life-affirming warmth moves in without necessarily tearing him apart.

Life’s hard enough – we need all the consolation we can get. I’m big on all this.

And that’s probably why I reacted so strongly when they eventually did sleep together.

Picking Up The Pieces

It wasn’t just disappointment or mixed feelings or having the sensation that I’d been led on the entire time (though it was certainly, at least in part, all of those things). I wondered if there was a majorly missed opportunity here. I thought the show would be insanely more relevant if Fleabag and the Priest never fell into bed (even if it was only once, even if they realized it was a bad idea, even if it did ruin everything).

I wanted a show suffused with humanity and a very particular form of heroism. What I got was a show about two insanely likeable people still working through their weird human bits who have to own up to their mistakes. I wanted something else, and that was my problem.

What I really needed to get over was myself. Fleabag didn’t portray her consummation with the Priest as something to be celebrated – it was a moment of regression for the both of them. The show demonstrated that these things have consequences. They didn’t get a happy ending – they might not be capable of a happy ending, at least maybe not without a kind of grace beyond human power. It showed that even though he broke with his integrity (potentially not for the first time), he returned to his vows and wasn’t treated as a crazy for it. He’s tragic, perhaps, but Fleabag herself is an intensely tragic figure.

They part amicably, both wounded and perhaps more human for their encounter. There’s no direct moral to the story, and Twitterati have been pronouncing their own interpretations of the relationship since.

Forgiving the Priest his humanity was necessary, and I wasn’t ready to do it right away. I placed certain expectations on him, and it reminded me that when I place astronomical expectations on the consecrated people in my life (without stopping to think about what their needs are, and whether they’re being met) I’m treating them as something inhuman. Superhuman, maybe, but nevertheless inhuman. The show grounds itself in a message that the clergy are human and need care otherwise they’re likely to act out in problematic but entirely understandable ways.

This was a man of God on screen, one in a weak moment who nevertheless does the right, painful thing in the end. He moves forward with a painful, complicated, maybe even enriching memory. And if that’s not good enough for me, then that probably says more about me than the Priest.

Fleabag’s second season was strikingly ambitious for rooting itself in this kind of tension, and it demands truckloads of empathy for a religious system typically ignored, reviled or satirized in contemporary art. It’s a story about two fractured people from entirely different worlds who have to process the nature of desire – it never reduces them to stereotypes or a party line. This made it far more remarkable than The Young or New Pope, and it never reduced its Priest to kitsch.

Kitsch here is a key idea to understanding just how revolutionary Fleabag‘s priest actually is. Before moving on to part three in this series (which will look at modern portrayals of nuns, to complement the above discussions of popes and priests), kitsch will be explored in it’s own post…one that will hopefully be up soon. Stay tuned.