“Mass of the Americas” and the Flourishing of Religious Culture

In our era, new musical Mass settings are rare. So, it’s notable that a new musical Mass was commissioned and premiered at a Mass celebrated by Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone in San Francisco last December. For this article, I interviewed by email the respected Bay Area traditional sacred music composer, Frank La Rocca, who composed the Mass. We discussed when it is legitimate to call a musical composition a “Mass” and how he was able to incorporate multiple languages and non-traditional musical instruments and elevate them into a composition suitable for the sacred liturgy of the Catholic Church.

On December 8, 2018, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, the “Mass of the Americas” premiered at San Francisco’s Cathedral of St. Mary of the Assumption. The Mass was celebrated by Archbishop Cordileone at the end of the 25th annual “Cruzada Guadalupana,” a 12-mile pilgrimage in honor of our Lady of Guadalupe—which is held every year on the closest Saturday to her feast day December 12. This popular annual event draws thousands, many of them Mexican-American, from around the Bay Area.

Mark Nowakowski—who is also a composer and who attended the “Mass of the Americas”—wrote in his review “Return to Liturgical Glory?” that even though many mass goers were exhausted from the pilgrimage, the music elicited their rapt attention.

This reaction was confirmed for me personally by Lety (Letitia) Hernandez, who cleans house for me once in a while. She lives near me in San José, an hour’s drive from San Francisco. She told me the next Monday—with great enthusiasm, in a mixture of Spanish and a little English—that she took part in the walk, attended the Mass, and (¡Me gusto mucho!) she liked the music very much.

The Mass was sung by a 16-voice choir and by soloists singing different parts, in Spanish, Latin, English. One hymn was sung in Nahuatl, the language in which Our Lady of Guadalupe spoke when she appeared to Saint Juan Diego. The singing was accompanied at various points by an equally unusual ensemble of organ, string quartet, bells and marimba.

Frank La Rocca, who composed “Mass of the Americas,” is a classically trained musician and composer, and he is the composer in residence for the Benedict XVI Institute for Sacred Music and Divine Worship—which was founded by Archbishop Cordileone.

When I first read the announcements at the Benedict XVI Institute website about the planned inclusion of multiple languages and non-traditional instruments in “Mass of the Americas,” I feared the result might be a hodgepodge that departed from the accepted traditional norms of musical Mass settings. But in the process of researching the Mass and interviewing its composer, I became convinced that Frank La Rocca deftly incorporated the non-traditional elements with the best possible understanding and reverence for what a Mass is supposed to be.

How It Came About

Mass of the Americas was envisioned by Archbishop Cordileone as an intertwined tribute to our Lady of the Immaculate Conception as Patroness of the United States and our Lady of Guadalupe as Patroness of all the Americas, with sacralized folk music. “I’m trying to model how the Church has always appropriately enculturated the Gospel by adapting aspects of the local culture, but within the sacred tradition”—Archbishop Cordileone

The quotes in this section are from “The Making of the Mass of the Americas” by Maggie Gallagher, the director of the Benedict XVI Institute, from an interview with La Rocca. More specifics about why and how La Rocca used various languages and instruments in the parts of his “Mass of the Americas” are in the complete Gallagher interview and in my own interview at the end of this article.

La Rocca at first resisted Archbishop Cordileone’s request. “I am a dyed-in-the-wool Western European classical composer. All of these things take me well outside the orbit of what I know.’” However, he conceded: “It is the job of a composer-in-residence to respond to commissions.”

In response to the commission, La Rocca researched the music of the Mission period, and the various versions of Mexican Marian folk hymns that the archbishop suggested, including Las Mananitas and La Guadalupana. “La Mananitas is the Mexican equivalent of Happy Birthday, although originally the tune was created for a text about the Virgin Mary and King David, so it has a devotional history even though it’s not used that way now. . . . La Guadalupana has always been, and it sounds like, a typical Mexican Mariachi tune: the oompah, oompah guitar, the crooning violins, and the two robust male singers. The challenge before me was to make the tune recognizable enough so anyone paying attention would sit up and say, ‘I know that,’ but with the words changed and the sounds of the guitars, the violins, and the voices lifted up and transformed.”

“That occupied a great deal of my time trying to figure out how close to the surface to bring the tune – how close to what listeners would be literally familiar with — in order for it to be recognized, and yet still get absorbed into the fabric of reverent music for the liturgy.” His challenge was to do it “in a musical style appropriate to the tune while taking it to sacred places that, for all I know, no other arranger ever has. . . . In some ways, it’s not that different than what many classical music composers have done over the centuries in incorporating folk tunes into the classical tradition.”

Frank La Rocca, “Mass of the Americas” Composer

Sixty-eight year old La Rocca has a B. A. in Music from Yale, and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Music from University of California at Berkeley. He was a cradle Catholic who left the Church as a young man and returned after forty-two years of being away. The first piece of sacred choral music he ever composed as a Catholic was his “Ave Maria,” which is included the “Mass of the Americas.”

He dedicated his “Ave Maria” to a friend, an old Cistercian Nun, Sister Columba Guare, O.C.S.O. When he sent it to her and told her he had come back to the Church, Sister Columba told him that her whole community at Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey in Iowa had been praying for his return! (You can listen to La Rocca’s “Ave Maria” here).

La Rocca has said he approaches his work in sacred choral music as “a kind of missionary work” and regards himself in that role “as an apologist for a distinctively Christian faith—not through doctrinal argument, but through the beauty of music.”

Now Some Terminology

Skip to the next section, “MOTA’s Use of the Ordinary,” if you already know what the terms Ordinary and Proper mean when they refer to prayers of the Mass.

The term Ordinary has many meanings in Church speak. Ordinary can mean “bishop.” Or it can be used as an adjective, as in “Ordinary Form,” the form of the Mass that was promulgated in 1969, or “Ordinary Time,” a part of the liturgical year in the Ordinary Form calendar. When the term Ordinary refers to Mass prayers, it means the set of prayers that do not change from day to day. The following table lists the Ordinary parts of the Mass that are sung during a Sung (High) Mass or Solemn High Mass.

The Proper (or Propers) consists of the set of prayers that change according to each day’s feast or place in the liturgical year. The following table shows the Proper prayers sung during a Sung (High) Mass.

MOTA’s Use of the Ordinary

La Rocca stayed true to the traditional practice of using the words of the Catholic Mass for his settings of the Ordinary. For example, La Rocca set the text of the Kyrie with each Greek verse preceded by a Spanish invocation (trope) from the Spanish translation of the Missal. For example, “Tú que vienes a visitar a tu pueblo con la paz. Kyrie Eleison.”

MOTA’s Use of Historic Hymns

La Rocca’s Mass included the music for three hymns that have deep roots in California history. The Processional (Entrance Hymn) “El Cantico del Alba,” the “Canticle of the Dawn,” is a morning hymn in Spanish to Our Lady. Historians have recorded that hymn was sung upon rising and on the way to Mass, by almost everyone, every day, and everywhere Catholics lived throughout Alta and Baja California, in the missions and the pueblos, during the years of Spanish and Mexican rule.

A unique musical setting by La Rocca was used for the Communion meditation. He set the text of a translation of “Aue Maria,” “Hail Mary” in the Nahuatl language, which he discovered in a collection used for teaching Nahuatl-speakers that was written in 1634 by a mixed-race missionary in Mexico who was fluent both in Spanish and in Nahuatl.

La Rocca’s Mass ended with a Recessional setting of the Latin Marian Antiphon for the season, “Alma Redemptoris Mater,” which melded gradually into counterpoint between “Alma” and the melody of “La Guadalupana,” a musical symbol of the unity Archbishop Cordileone asked La Rocca to embody in the work. As La Rocca explained, the tune of La Guadalupana was “elevated into a high classical sacred musical language” to suit the reverence due the liturgy. The tune was also subtly woven into a number of other movements, most notably the Gloria.

The words themselves are charming; they tell about how Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared to Juan Diego, in the form of a young native woman, how she asked for an altar in her honor to be built on the hill where she appeared, and how from the time she appeared she has been the mother of all peoples in Mexico. Pope John Paul II canonized Juan Diego in 2002 and declared Our Lady of Guadalupe the patroness of the all the Americas.

Taking “Mass of the Americas” on the Road

It is unusual for a new musical composition to ever be heard again after its premiere. As Mark Nowakowski wrote in his review quoted earlier:

“For a composition to become something for the ages, the biggest chasm is between the first performance and the elusive and the (for most) unattainable second performance.”

A sign that the “Mass of the Americas” may have the potential for lasting and perhaps classical status is that the Benedict XVI Institute has booked performances at other Marian Cathedrals in other parts of the U.S. and other countries as part of what they call a Marian International Unity Tour.

The music was performed for the second time at an Ordinary Form Mass celebrated by Archbishop Cordileone in Tijuana, Mexico, on February 28, 2019, at S. Maria Estrella del Mar, during a Mexican national liturgy conference hosted by Archbishop Francisco Moreno Barrón of Tijuana.

An adapted score will be used when Archbishop Cordileone celebrates an Extraordinary Form Mass at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, in Washington, D.C. on November 16, 2019.

Additional performances during Ordinary Form Masses are currently booked (dates to be announced) in Dallas, Texas, at Our Lady of Guadalupe Cathedral, and in Mexico City (venue not yet specified) next summer.

By request from organizers in Houston, a concert version has also been created, which will be performed there twice (once at the Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart on November 24). And they will bring the concert version to Rome in June 2020.

According to the Benedict XVI Institute’s website, “More cities are being added monthly.”

Interview with Frank La Rocca

RTS: Am I right that over the course of music history most composers wrote musical Mass settings using the texts of the Ordinary parts of the Mass in Greek for the Kyrie and in Latin for the remaining Ordinary prayers?

FLR: Yes.

RTS: I have the impression that composers wrote Masses to show off their chops . . .

FLR: Depends on the time period. Medieval/Renaissance era Masses were written for liturgy, and while some of them were rather grand, it was always to elevate some special feast or personage, such as a pope or cardinal, not primarily the individual composer’s recognition.

After that, beautiful, magnificent Masses as demonstrations of compositional prowess—and never intended for liturgy—emerged: Bach, Mozart, Schubert, Beethoven, and so forth.

RTS: And is it true that some secular composers starting in the 20th Century began to write performance pieces titled Masses, but which departed greatly from the words and intention of the Mass?

FLR: Most definitely. In the 20th century the Mass became co-opted as a template for pushing political and social agendas by hijacking the history and prestige of the Mass.

RTS: I’m thinking of Leonard Bernstein’s “Mass” in 1971, which I think is sacrilegious––even though Pope Saint John Paul II invited that Mass to be performed (with the blatantly offensive parts removed) during the year 2000 in the Paul VI Audience Hall at the Vatican.

FLR: It is [sacrilegious]. It’s musical theater, not sacred music–even considered as concert music. Many such pieces [have been written], with various social and political agendas.

RTS: There was also a “Mass of Freedom” composed for and performed by the Oakland Symphony Chorus last Spring that used African-American spirituals that evolved as protest songs and used only a few words from the actual texts of the Mass. How do you account for the use of the term Mass for something that is not a Mass?

FLR: Gradual drift. First, we have the creation of magnificent non-liturgical works, like the Bach B-minor Mass, Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis.” Then, the possibility of a non-liturgical Mass having been established, in the 20th century it became a platform for almost any other issue you want to imagine. But, being a “Mass,” it smuggles in a prestige and gravitas that these “Masses,” in fact, have no right to claim.

RTS: You have written several traditional Masses. When you wrote your other Masses did you use Gregorian chant and polyphony for the music? Did you set the Ordinary in Latin to music?

FLR: I set the Ordinary, and I use a style of polyphony clearly derived from, but not identical to the Renaissance style. If I wanted actual chant, I would quote actual chant since it is a body of work that cannot be surpassed, only adapted or arranged. Chant is for Propers in a polyphonic Mass, so I would have the existing Proper chants used rather than incorporating them into any Mass I composed.

RTS: Is your “Mass of the Americas” a setting of the Ordinary also? Or are other words used? I know that the “Aue Maria” is in Nahuatl. Did you follow the traditional practice of using hymns in addition to the Ordinary? Were the different parts of the Ordinary in the various languages? Or did you use multiple languages in any of the individual parts?

Bringing Up the Gifts at Mass of the Americas Premier

FLR: “Mass of the Americas” as it was premiered in December is a Mass in the Ordinary Form. It is a setting of the Mass Ordinary, plus an Alleluia, Memorial Acclamation/ Amen, Offertory) bookended with a Processional (an arrangement of the traditional Mexican “Cantico del Alba”) and a Recessional (“Alma Redemptoris Mater”).

I use Latin (Kyrie [Greek]/Gloria/Offertory [Ave Maria]/Sanctus/Alma Redemptoris), Spanish (Kyrie tropes/Benedictus [“Bendito”], Cantico del Alba), English (Memorial Acclamation/Agnus Dei) and — only for a non-liturgical Communion “meditation” — a song for soprano, violin, marimba and organ setting the “Ave Maria” in Nahuatl.

RTS: My next question is about the use of multiple musical instruments in the Mass. When I sang for a few years with the St. Ann Choir, which is directed by Stanford Professor William Mahrt, who is president of the Church Music Association of America, and editor of the Sacred Music journal, and I began my amateur but avid study of sacred music, I learned that the organ is considered to be the proper instrument for liturgy.

“The employment of the piano is forbidden in church, as is also that of noisy or frivolous instruments such as drums, cymbals, bells and the like.”—Pope St. Pius X

Professor Mahrt said if you bring secular instruments into the Mass they can bring distracting associations in with them, and he used the example of a piano with its associations with a barroom. Knowing your deep faith and your expertise and how you have composed several Mass settings for both forms of the Mass, I have no doubt that you respectfully considered these things. Can you share your thinking?

FLA: The use of strings is not controversial, but some may wonder about the guitar, handbells and marimba.

The handbells are used only during the processional and recessional, and they are intended to evoke the bells of a church bell tower, recreating the experience of the early Mission Mass-goers as they processed to Mass singing “Cantico del Alba.” Bells, of course, are used by many churches at the Consecration as a sign of the holiness of the moment, surrounding the Consecration (as with incense) in a cloud of sound – I’m pretty sure Pope St. Pius X did not object to their use when properly employed.

The guitar found its way into the Mass in an effort to evoke the sound of Mission Masses in the early days of California, where the guitar was used (along with string quartet) to supply harmonic support for singing. Its use in that context is well-documented, and my use of it was a nod to that historical practice.

The marimba is used only in a paraliturgical Communion “meditation” and was chosen because it is an instrument native to the land where Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared to Juan Diego. It is used with a special tremolo technique that gives it a sound very much like a deep, mellow organ stop – not a clamorous rhythmic instrument.

RTS: A provision about the use of instruments other than the organ is stated in several Church documents including Pius X’s Cæremoniale Episcoporum “that permission for their use should first be obtained from the ordinary.” Am I right that that permission was obviously obtained because Archbishop Cordileone was the one who commissioned the Mass and asked for these non-traditional instruments?

FLA: Yes. The idea for the marimba was mine, but he approved.

RTS: Have you had any pushback from people who are against multilingual Masses? When Masses are celebrated with multiple languages used for various parts of the Mass, with the goal to unify all the speakers of different languages, doesn’t the fact still remain that most of those present will only understand those parts that are in their own language? Won’t they be unified mostly by the fact that their language is included? Can you help me change my mind if that’s not true?

FLA: One comment I received, typical of quite a few others attending the Mass was:

“As a Mexican, I found the music particularly moving. Hearing the sounds of folk/traditional Mexican song, such as “Las Mañanitas,“ married/interwoven with the high/sacred arrangement, moved me literally to tears. It spoke deeply to my heart and memories. It made me feel okay to take pride in, as Archbishop Cordileone said, paraphrasing the psalms, the fact that “He has not done this for any other nation…”

The purpose of using Latin, Spanish and English was to realize one of the primary goals of the Mass – representing the underlying unity of our Catholic identity under the protection of the Virgin Mary, who is Patroness of the United States (an English-speaking country) and all of the Americas. Since this Mass was a Festal Celebration of our Lady of Guadalupe, and an event organized and attended by primarily Spanish-speaking Catholics, I use that tongue. I also used Spanish so that those speakers could hear High Church, reverent music setting their language and elevating it in a way that many, if not most of them had never before heard. I believe it opened minds and hearts to the beauty of traditional sacred music for the Mass.

The Nahuatl of the Communion Meditation was used because that is the language in which Our Lady addressed Juan Diego. But most of the Mass is actually in Latin, however, acknowledging our ancient unity around that language.

RTS: Some would bring up my previously stated objections as also being valid against the use of Latin, but many popes have written that the universal use of Latin was a powerful sign of the Church’s unity. Once you learned to follow the traditional Latin Mass, you could attend the Mass with understanding in any Church in the world. Pope Benedict XVI recommended the use of Latin in any large Mass that would be attended by people from many countries, for that very reason. Jan Halisky, a lawyer who co-founded Familia Sancti Hieronymi, an association of people who seek to keep the Latin language alive by learning, speaking, and studying texts in Latin, wrote this to me recently, “For centuries the Church had the solution to mixed congregations, and that was the Latin Mass, which the congregations knew from weekly encounters.” What are your thoughts about this point of view?

FLA: As a guiding principle, I agree completely. But should this principle have been applied in such a way as to make the creation of the Mass of the Americas impossible? Given all the other goods that have flowed from it, clearly I do not think so. Should the Gospel not have been translated into Saxon, for example, when the Missionaries went out from Rome to evangelize those peoples early in the first millennium A.D.? Should St. Thomas Aquinas not have imported concepts from pagan philosophy that would allow the Church to deepen her self-understanding?

RTS: Of course translating the Gospel into Saxon and St. Thomas Aquinas’ assimilation of Aristotle were right to do. My questions are specifically about whether multiple languages should be included in a Mass when it results in some not understanding parts of the Mass.

FLA: I think the Mass of the Americas is a proper application of the principle of enculturation that Holy Mother Church has used throughout the centuries. It is, both literally and figuratively, a Missionary Mass.

RTS: Fair enough. You recently adapted the “Mass of the Americas” for the Extraordinary Form of the Mass. In your Ordinary Form version, you had multiple languages. What did you need to do to adapt the original version?

FLR: The entire EF Ordinary is, indeed, in Latin, and that entailed composing a new Kyrie and new Agnus Dei, as well as changing the Benedictus (with the same music) from Spanish to Latin. The Offertory will be my “Ave Maria,” already in Latin.

It’s High Mass, so all the remaining Propers and the Credo are to be chanted. Any other Propers and Ordinary prayers not listed in the following sequence will be the chants from the Extraordinary Form “Missa Salve Sancte Parens.” The Propers are being reviewed by Archbishop Cordileone and his Master of Ceremonies. There is no doubt it will be absolutely correct.

Processional (La Rocca’s arrangement of the traditional Mexican “Cantico del Alba”)

Kyrie (newly composed in Greek for EF Mass)

Gloria (Latin same as in OF Mass)

Offertory (La Rocca’s “Ave Maria”)

Sanctus (Latin same as in OF Mass)

Benedictus (rewritten in Latin for EF Mass)

Agnus Dei (newly composed in Latin for EF Mass)

“Aue Maria” in Nahuatl — a song for soprano, violin, marimba and organ (to be sung during the ritual de-vesting of the archbishop, which takes place at the altar, but after the “official” end of the Mass)

Recessional (Seasonal Marian Antiphon, “Salve Regina” in Latin, newly composed, melding with and embracing “La Guadalupana,” like the “Alma Redemptoris Mater” arrangement used in the season when the Mass was first celebrated)

Alleluia and Credo from Liber/Missal

String section expanded to 10 players (compared with quartet in San Francisco), otherwise same instruments.

All compositions are the same, note for note, as in San Francisco, except for the new Kyrie, Agnus Dei, and Salve Regina.

The following table shows the parts of the two Masses side by side for easier comparison of the differences and similarities.

Mass Music from the Mission Days

As La Rocca mentioned in the above interview, strong precedent for the use of multiple instruments in “Mass of the Americas” can be seen in the music taught to the converted indigenous people by Franciscan missionaries during the time of the California Missions. The friars, including Saint Junípero Serra, Fathers José Viader, Felipe Arroyo de la Cuesta, Estevan Tapís, and especially Narciso Durán, dedicated themselves to teaching the converts how to sing chant and polyphony and play instruments during Masses.

While I was a member of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Oratory choir in San José, I had the privilege of singing the alto part in a Mass setting that is called the “California Mission Mass” at Mission San Rafael and at Mission Santa Clara. The “California Mission Mass” was arranged by composer John Biggs from music written down by the missionaries for the converted Native Americans to sing and play at Masses, which Biggs selected from various Masses archived at Mission Santa Barbara. The use of instruments during the early mission masses is proven by how the music was scored for flute, violin, cello, string bass, and hand bells in addition to the high and low voices.

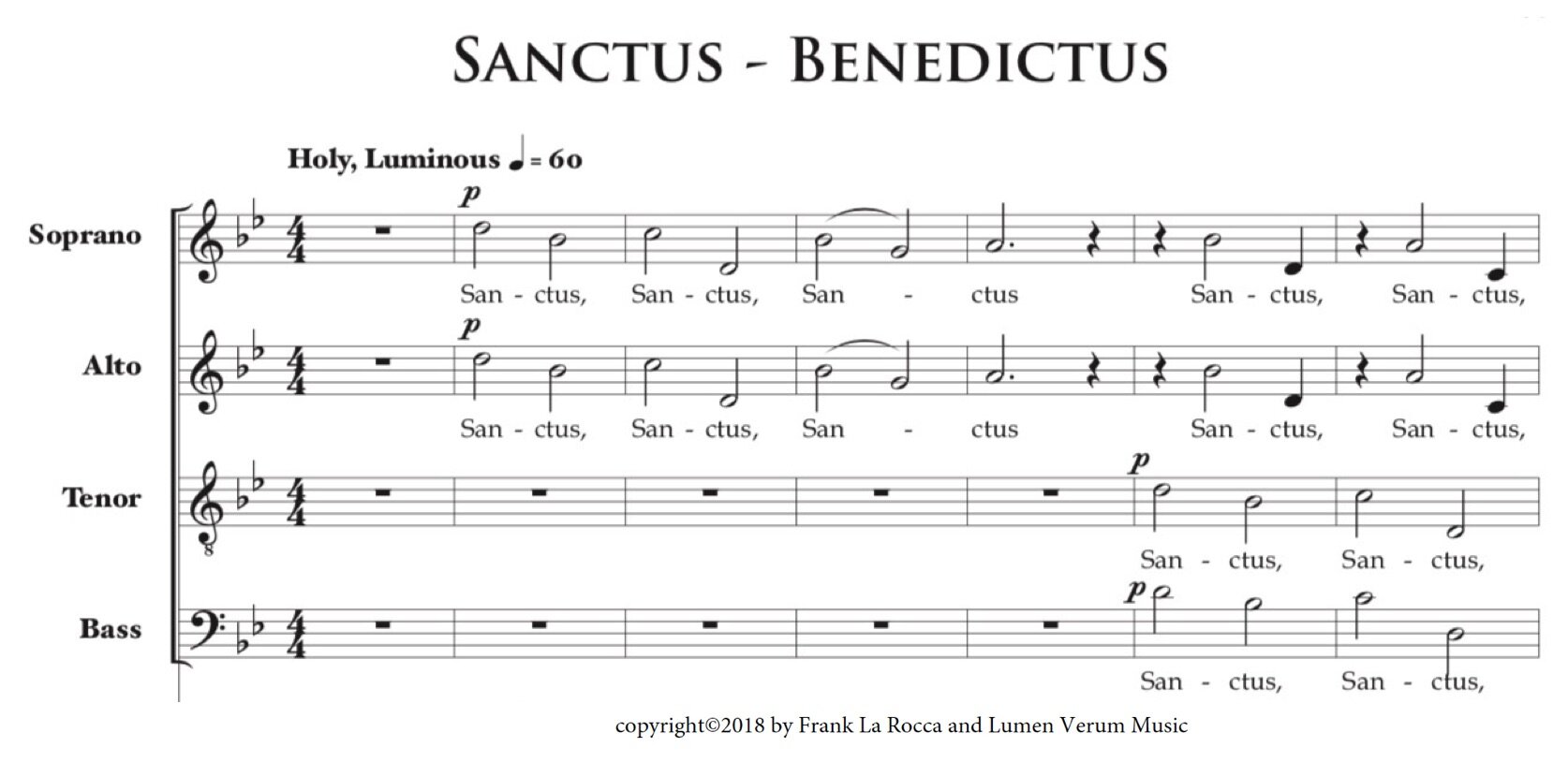

For example, this snippet from the Sanctus/Benedictus from “California Mission Mass” shows it was scored for bell, violins, cello, and string bass.

For the sake of comparison, here is the beginning of La Rocca’s Sanctus/Benedictus Click the image to view a PDF of the full page, which shows how the piece is scored for the Violin, Viola, Cello, Double Bass, Guitar, and Organ.

“El Cantico del Alba,” the Spanish Processional hymn of “Mass of the Americas,” was also part of the music of the California missions.

You can watch and listen to the playlist of the San Francisco premiere of “Mass of the Americas” in the videos here.

You can watch the whole Mass in an EWTN episode of “Cathedrals Across America.”

James Matthew Wilson Writes a Poem About It

The Benedict XVI Institute also commissioned professor and poet James Matthew Wilson to fly from Villanova University in Pennsylvania to San Francisco for the premier of the “Mass of Americas” and to write a poem about it. The seven-poem cycle Wilson wrote in response is titled “The River of the Immaculate Conception,” and it is being published by Wiseblood Books. A pre-release copy of the poem is waiting on my desk for my attention. An interview with Wilson about the poem is coming soon. In the meantime, here is an apt closing quote from Wilson (in prose) published by the Benedict XVI Institute about the “Mass of Americas.”

“This is what a flourishing religious culture looks like—piety being lifted up and sublimated in the actual liturgy of the Church.”—James Matthew Wilson