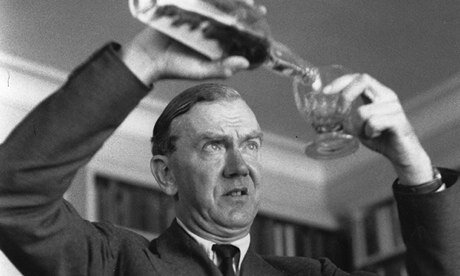

Happy Birthday, Graham Greene

Graham Greene was born in Berkhamsted, England, on October 2, 1904, and so Greene would be 113 years old this year. As most Dappled Things readers probably know, Greene grew up to be a quite-famous Catholic novelist, even though he didn’t like being labeled a Catholic novelist.

It’s hard to avoid thinking about him that way, since Greene’s greatest novels—Brighton Rock (1938), The Power and the Glory (1940), The Heart of the Matter (1948), and The End of the Affair (1951)—and others of his works treated Catholic themes.

I love this interchange between Greene and Evelyn Waugh, another great Catholic novelist with whom he was often linked, after Greene’s publication of The End of the Affair.

“About a year after its publication Greene told Evelyn Waugh that he wanted to write a political novel. ‘It would be fun to deal with politics,’ he said, ‘and not always write about God.’ … ‘I wouldn’t give up writing about God at this stage if I was you,’ he replied. ‘It would be like PG Wodehouse dropping Jeeves halfway through the Wooster series.’”—The 100 best novels: No 71 – The End of the Affair by Graham Greene (1951)

Several of Greene’s novels were made into successful films, including the Orson-Welles-directed The Third Man, The Quiet American, and the quite exceptionally funny, Our Man in Havana, with Alec Guinness in the starring role as a vacuum cleaner salesman turned spy, and Maureen O’Hara as his fellow spy and love interest. Greene liked to poke fun at spies. He had been a spy himself, and he stayed a life-long friend of fellow-spy Kim Philby, who was a notorious mole who defected to Russia (although that’s no laughing matter).

Greene met his future wife Vivien Dayrell-Browning when she wrote him to point out some errors regarding Catholicism in his writings. Greene converted to Catholicism partly through Vivian’s influence, but his numerous infidelities and his way of life in general were a contradiction to his faith.

This was the paradox that Greene carried within himself: He professed the reality of the Faith but chose not to practice it.–Edward Short, “Faith and Failure in Graham Greene”

Greene told an interviewer that he didn’t think God cared much about what the Church calls “sins of the flesh.”

I remember reading The Power and the Glory as a teenager, and I was repelled by his main character, a whiskey priest who fathered an illegitimate child, and who was hiding from a Mexican policeman who was tracking him down during the Cristeros War. Even though I avidly read most if not all of Greene’s books decades later, and re-read several of them, I’ve never wanted to go back to The Power and the Glory and get lost in the woods and swamps with the fugitive priest’s thoughts again.

The way I remember the priest’s state of mind, he was tormented by the conviction he would be damned if he was caught and killed because he couldn’t find another priest to confess to, and to my matter-of-fact way of thinking, his big dilemma was no big deal at all. As a priest, he should have known better, I thought. In parochial school we had been taught that a sincere act of contrition with the intention to go to confession as soon as possible can obtain forgiveness of mortal sin.

So when I learned decades later that The Power and the Glory had been censured by the Vatican, I thought Greene’s apparent misunderstanding about confession might have been the cause. As it turns out, the reasons why the book attracted the Vatican’s attention were a lot more complicated than that. The whole story is told quite well in The Atlantic in “Vatican Dossier,” by Peter Godman. Here is a quote from one of the Vatican consultants who commented on the book.

Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh, according to expert opinion, are to be considered the two major living English novelists: being Catholic they do credit to Rome’s faith, and they do credit to it in a country that is of Protestant civilization and culture. … Their level is the higher intelligentsia in the contemporary world which they sway and influence towards Rome … In the case of Graham Greene, his harsh and acerbic art touches the hearts of the least receptive and reminds them, however gloomy they be, of the awe-inspiring presence of God and the poisonous bite of sin. He addresses those who are most distant and hostile—those whom we will never reach …”–Monsignor Giuseppe De Luca in a November 30, 1953 memorandum to the Holy Office.

As it turned out, Greene was later informed of the Holy Office’s “negative judgment,” to “exhort him to lend a more constructive tone to his books, from a Catholic point of view.”

In Ways of Escape, Greene wrote of an audience he had years later with Pope Paul VI, in which Greene told the pope that The Power and the Glory had been censured. The pope reassured him, “Mr. Greene, some aspects of your books are certain to offend some Catholics, but you should pay no attention to that.”

Peter Godman was intrigued by that story, and in 2000, Godman obtained consent from Cardinal Ratzinger to investigate the censure in the archives for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The Atlantic‘s “Vatican Dossier” article is the result of Godman’s investigations.

Pope Paul VI did not let on to Greene that he knew far more than he was letting on at the time of the audience. The “Vatican Dossier” article revealed that Paul VI had written a favorable opinion to the Holy Office about The Power and the Glory when he was Cardinal Giovanni Bautista Montini, and his opinion led to a softening of the stance that the Holy Office eventually took about the book.

Greene on the Traditional Latin Mass

Graham Greene was one of the signatories (along with many other writers and well-known intellectuals) on a petition that was sent to Pope Paul VI and resulted in the Agatha Christi Indult.

Greene confessed in his last extended interview before his death in 1991 that he still loved to attend the Mass in Latin, which his friend, the Spanish priest Father Leopoldo Duran, had his bishop’s permission to say.

Though he welcomed the ecumenical spirit of the Council and its consequent stress on faith and justice, his Catholic identity was much tested by his personal distaste for the vernacular liturgy. Greene felt there was a diminishment of the supreme power, aura, and aesthetic beauty that the liturgy had traditionally played in the imagination of Catholics. In this respect he agreed with other, more traditional English converts concerning the liturgical changes begun by Vatican II. In 1967 Greene was asked by the International Committee on English in the Liturgy to critique and offer suggestions on the translations of the Mass. He dutifully did so but expressed his profound disappointment if the Latin Mass were ever lost in the process. By 1971 Greene had signed with other Catholic artists and intellectuals an appeal sent to the Vatican, asking that the ‘Tridentine Mass be preserved in both language and structure.’ He complained in interviews about not being able to follow the vernacular Mass in the many places he traveled, his annoyance with the ‘freedom given to priests to introduce endless prayers–for the astronauts or what have you,’ and his grief over the abolition of the reading from John’s Gospel that used to end the Tridentine liturgy….”–Graham Greene’s Catholic Imagination, by Mark Bosco, S.J., Oxford University Press 2005.

Green on His Catholicism

The following quotes from Green about his Catholic faith are from a New York Times interview (“Selection; The Uneasy Catholicism Of Graham Greene”)

I’ve told you, my conversion was not in the least an emotional affair. It was purely intellectual. It was the arguments of Father Trollope at Nottingham which persuaded me that God’s existence was a probability.

(When I was baptized, I made it clear that I had chosen the name of Thomas to identify myself not with St. Thomas Aquinas but with St. Thomas Didymus, the doubter.) I eventually came to accept the existence of God not as an absolute truth but as a provisional one.

I have also seen with my own eyes the stigmata on Padre Pio’s hands in the south of Italy. … I was so convinced of his powers of goodness that I refused to approach him and speak with him. I explained to the friends who had brought me along that I was too afraid that it might upset my entire life.

I think that the flatness of E.M. Forster’s characters and Virginia Woolf’s or Sartre’s, for example, compared with the astonishing vitality of Bloom in Joyce’s ”Ulysses” or of Balzac’s Pere Goriot or David Copperfield, derives from the absence of the religious dimension in the former. Francois Mauriac’s characters are equally endowed with this strange substantiality. In ”La Pharisienne,” when one of them – a very minor character – crosses a schoolyard, we have a sense of having seen him in flesh and blood, while Mrs. Dalloway doing her shopping leaves one indifferent.

I’ve broken the rules. They are rules I respect, so I haven’t been to Communion for nearly 30 years… In my private life, my situation is not regular. If I went to Communion, I would have to confess and make promises. I prefer to excommunicate myself.”