My First and Last Resort (Mazatlán) - Part I

I never particularly wanted to travel to a resort, because I prefer more active and less insulated ways to visit other parts of the world, but during one week at the end of October and the beginning of November in 2001, my grown son Liberty and I stayed at a friend's condominium at the El Cid timeshare resort in the area called the Zona Dorada, or Golden Zone, in Mazatlán, Mexico. I felt a bit guilty to be staying at a resort for people who had money to spare in the middle of a lot of poverty. My friend, Annette, had invited us in gratitude for a favor I had done for her, and so I went as another kind of favor, in response to her generosity. I did have a great time while I was there, practicing my rudimentary Spanish on the locals, swimming, and sketching, and trying to experience as much as possible of what life in Mazatlan is like, not only for tourists but also for the people who live there away from the resort.

This post contains some excerpts from my adventures.

El Moro Torre, El Cid Resort, Zona Dorada, Mazatlán

Getting Out of the Golden Zone

With two time-share pitches to earn some rewards and to learn from an anthropological sort of perspective more about the world of timeshares, a boat tour of some local islands with a picnic, which was one of our rewards, a Fiesta Mexicana at the hotel, which was another reward, and with blissful hours in the connecting series of pools around the building and in the waves at the truly beautiful beach out front, we were busy and happy for the first three days, just sticking close to the resort.

Annette brought us to a local tourist bar called Senor Frog’s on Wednesday night. (But that’s a whole other story.) Thursday morning was the first time I ventured out of the resort area in the daytime. At 9:30 a.m. my son, Annette, and I took one of the unique-to-Mazatlán open air taxis to downtown Mazatlán (called El Centro Histórico, or El Centro for short) to attend a 10 o’clock Mass for All Saint’s Day. That type of taxi is called a pulmonia, which means pneumonia. As the story has it, when open air taxis started being driven in Mazatlán in the 1960s, jealous taxi drivers would warn passengers that they would catch pneumonia if they rode around in them.

Because the woman at the front desk reached the limits of her hotel-clerk English when I asked her to get me the Mass schedule, she erroneously gave us the Sunday schedule, which offers Masses every hour. We found out after we got there that next Mass on the holy day would not actually be celebrated until noon, so we had to wait around for two hours in the heat until the Mass began.

The area around the 16th century Catedral Basílica de la Inmaculada Concepción, with its crowded, narrow streets and narrow sidewalks, provided a vivid contrast to the resort. I remember one store stacked floor to ceiling with bolts of fabric, which had no permanent front wall, was fully open to the street, and would be locked and protected by a rolled-down metal shutter only at night. In front of the store, a vendor with a cardboard tray hung from a string around his neck was selling the same type of rich coconut cookies that had been offered as one of the dessert choices in the buffet at the Fiesta Mexicana at the resort the night before.

Beggars lay in front of the gates to the cathedral, a line of poor people waited at a back entrance for donations from the cathedral office, and many well off people crowded onto the escalators with us in the upscale department store across the street, where we went to find a restroom after the Mass.

Getting Into the Dump Zone

Saturday morning I left the world of the resort for a second time, this time to volunteer at a Christian children’s feeding center in one of several new Mazatlán communities. I volunteered with a Protestant group instead of a Catholic-sponsored one, because I hadn’t been able to find a opportunity online to volunteer with Catholics.

I had found out about the organization called La Viña (the Vineyard) Christian Fellowship in an ad in the Pearl of the Pacific, a Mazatlán newsletter on the Internet before I left California. La Viña has missions in several communities around Mazatlán. The place I visited with them that day is called Colonia Urias, which is a neighborhood that had recently been created below the Mazatlán dump.

First I walked about a mile to the La Viña location from El Moro Torro. Then I rode along with some volunteers in an old truck to the colonia. In the truck’s open bed, two white wooden benches lined with volunteers faced each other. I learned later that type of truck is called an auriga and that the name, interestingly enough, came from the Latin word used for a charioteer in ancient Roman.

Only one man, who is a missionary from England who now lives in central Mexico, spoke fluent English. The English missionary put me in the front seat with a trim middle-class fortyish local woman with aluminum caps on some of her teeth and with another local resident, a handsome well groomed young man of about 18, who, the Englishman told me, would be attending the university next year.

The woman spoke no English, the student spoke some, but less than the waiters at the hotel. The young man drove. We stopped for gas and then rode for almost an hour.

Somehow we kept a conversation going. I asked the woman, who introduced herself as Yolanda, about her children. The word she used to describe them sounded to me like cansada, which means tired. I said, “Cansada?” and tilted my head to the side, closed my eyes and pretended to snore lightly. She laughed and repeated the word, until I realized she was saying that her children are married, not sleepy. Oh, casado, not cansada! We laughed together.

The auriga’s windshield was dirty and cracked. Sometimes as I looked out of my passenger window while we at first drove through poorer parts of the city near the airport and then lurched along narrow dirt streets in the settlement, I wondered if I hadn’t made a mistake getting into a truck with a load of strangers within an unclear goal going to an unknown destination. But then I thought, not for the first time−”What the heck?”

Before leaving the paved road, we passed two cemeteries fenced with low adobe walls. It was November 3, the day after El Dia de Los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, when traditional Mexicans party in the cemeteries, bringing offerings of favorite foods and drinks and decorations to their loved ones’ graves. That day after the celebration, I noticed as we drove by that the cemeteries appeared to be almost completely carpeted wall to wall with bright flowers, both real and artificially made out of colored paper.

At the Colonia Urias, as they have done at several other colonias, La Viña Christian Fellowship has built a large hall. The Englishman told me the pastor assigned to this colonia and his wife are both dentists, and they routinely provide free dental care to the children of the colonia.

Every Saturday the volunteers lead the children in songs about how Jesus loves us, and they serve the children a meal. That day, the meal was a plate of fresh tortillas, refried beans, macaroni and carrot salad, and beef carne asada. Oddly, it seemed to me, they cover each plate with plastic bag and put the food on top of the plastic. Later I learned that water is scarce. The only water that comes into the colonia comes in by truck, and residents pay a fee to fill containers from the truck. The La Viña volunteers take the bag off the plate and discard it after the meal because they don’t have water available for washing dishes.

When I was introduced to the pastor’s wife, she wrapped her hand in a part of a black plastic garbage bag before she would shake hands with me. I looked confused. She said, “It’s . . .” and groped for the word for dirty. “Es sucio (dirty)?” I volunteered. She said, “Si, sucio.” And we smiled at each other. I thanked her for what she was doing there.

The Englishman told me that people in Colonia Urias used to make their living salvaging materials from the dump, as people still do in many other 3rd world countries, and as many people still do who live on the nearby dump in Mazatlán. In cultures where many people are so poor that they make a scarce living by scavenging in dumps, nothing is wasted. As we were driving into the area, I caught a glimpse of two men sitting close together on overturned plastic barrels, talking seriously over a small motor that one man held in his hand.

My impression was that everyone was well dressed, clean, and well fed. How they keep themselves and their clothes so clean with such a shortage of water is a good question. They are not rich, as we are, but they did not seem abject to me. I wish I’d asked what the people at Colonia Urias do to make a living now that they weren’t involved in the squalid back-breaking labor of picking out every little bit of anything that could be retrieved and reused from the refuse of the city. The tiny adobe houses we passed on the dirt streets looked clean and pleasant-looking enough, even if they lack most amenities that we think of as necessities.

Incidentally, I believe that the worse thing that “charitable” people can do is to make people see themselves as pitiable. My beliefs in that area were formed by being on the receiving end of institutionalized charity. I remembered how my widowed mother used to take me and my two sisters to Christmas parties thrown weeks ahead of Christmas by the firemen of Boston for poor families. Even as a very small child, I didn’t enjoy the events or the charity. To my thinking, it wasn’t really a Christmas party because it wasn’t Christmas yet. And it wasn’t personal.

Think of the difference between being at a party at work as a member of a large group that you aren’t comfortable with and being given a birthday party by people who care about you. Most people I know try to get out of work parties that are held during non-work hours. I’ve been to a lot of lavish affairs catered by tech companies I worked for, such as a party that took over the entire Monterey Bay Aquarium; they had sushi stations set up throughout (and I mock-seriously sympathized with the poor fish in the floor-to-ceiling tanks who had to witness others of their species served up raw with wasabi and rice). Back to the topic of anonymous events, I think that other people at least subconsciously feel the same way I do, that even if such a large group event includes great food and entertainment in luxurious surroundings, a good time isn’t really satisfying unless friendship or family affection is included in the mix.

At events like the one I was witnessing at Colonia Urias, generosity and self-sacrifice and a desire to help were evident, but there was little if any individual contact. As I watched the goings on, I speculated that the children might come to the hall mainly out of boredom–it’s the happening place every Saturday.

When I came into the hall, the Englishman offered me a white plastic seat. I took it and not knowing what else to do, sat on the sidelines. I thought maybe I could do something useful by just getting to know some of the people there personally. Some of the volunteers set to work to prepare the meal, and some dispensed lemonade they had mixed a big orange and yellow plastic McDonalds drink dispenser. Other volunteers lined up, facing towards the clump of over a hundred children who were squirming in their white plastic chairs. The volunteers at the front struggled to capture and keep the attention of the kids to lead them in the songs.

The pastor’s wife put her hand to everything, sometimes in the kitchen, sometimes in the group of song leaders, sometimes at the lemonade dispensing table. In the line of four or five volunteers leading the songs, one bearded pastor had a tee shirt saying in English “Get a Life. Meet Jesus.” A woman volunteer’s sports shirt had the Corona beer logo on the back topped by a gold crown (corona). Instead of the name of the beer, the shirt reads, “Sola El Señor Salva,” “Only the Lord Saves.”

As soon as I sat down, I quickly became surrounded by a half circle of kids in chairs and two baby strollers facing me directly. Unfortunately for politeness sake, this impromptu arrangement put the kids’ backs to the song leaders. But I didn’t know how to remedy it.

A nine year old girl, Anita, was the first to join me. She sat next to me on my right with her fourteen-month-old sister facing me in a stroller. Anita then introduced her seven-year-old middle sister, who pulled over her chair facing me also, followed by her ten-year-old brother with yet another chair. We all chatted as best we could with my limited Spanish.

During the time I sat with her, I let Anita take some photos with my Canon Rebel SLR, and I took some too. When I complimented a nearby twenty-something woman (also with aluminum caps on her teeth) on her pretty baby, she joined me too, pulling her chair and her baby stroller to my left side. The baby was dressed in a brand new immaculate pink dress and frilly pink headband.

In Spanish, the mother told me proudly that her baby’s name is Brianna, she is eighteen day old, and that her Bubby is Americano. When I asked, I thought she said that Bubby is a diminutive like Daddy). Later she said she met the child’s father in Las Vegas. Still later I learned that bubby in English means your one true love and there doesn’t seem to be a word like that in Spanish.

My jaw still drops a little when I remember how proud she seemed to be about getting pregnant from an encounter in Vegas. When I looked more closely, I noticed that the baby had fair skin and blue eyes. When she wasn’t nursing, the baby slept happily in the heat and the noise and the admiration of her mother and me. And it goes without saying, in the love of God, her Father in heaven.

Part way during our visit at the colonia the woman volunteer that I had been sitting with in the auriga, Yolanda, came up to me where I was sitting and said some things I didn’t understand. But she also said we are hermanas, sisters, and I understood that. I know that we are all sisters and brothers because we are sons and daughters of God, and I love to find others who recognize that very real kinship.

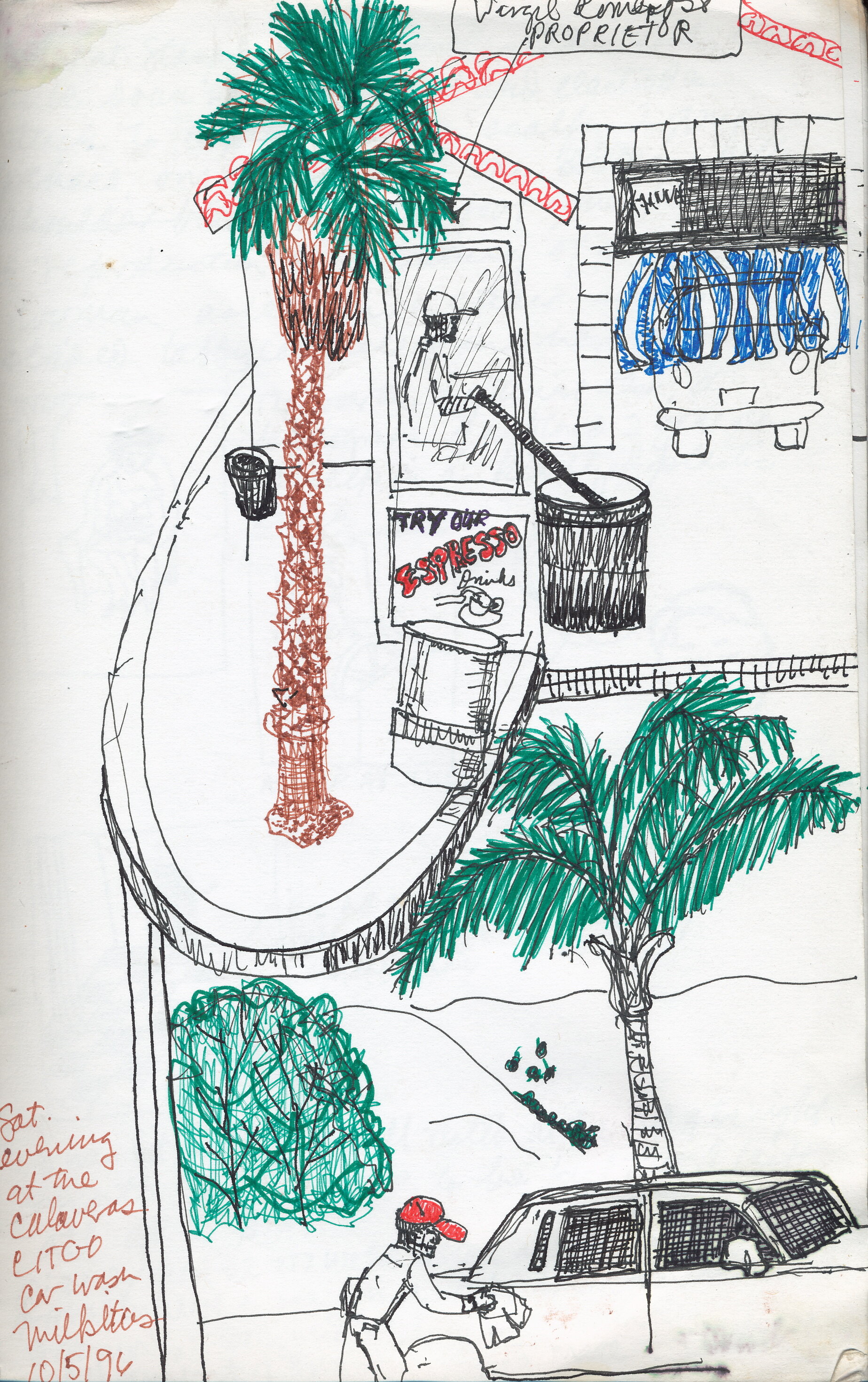

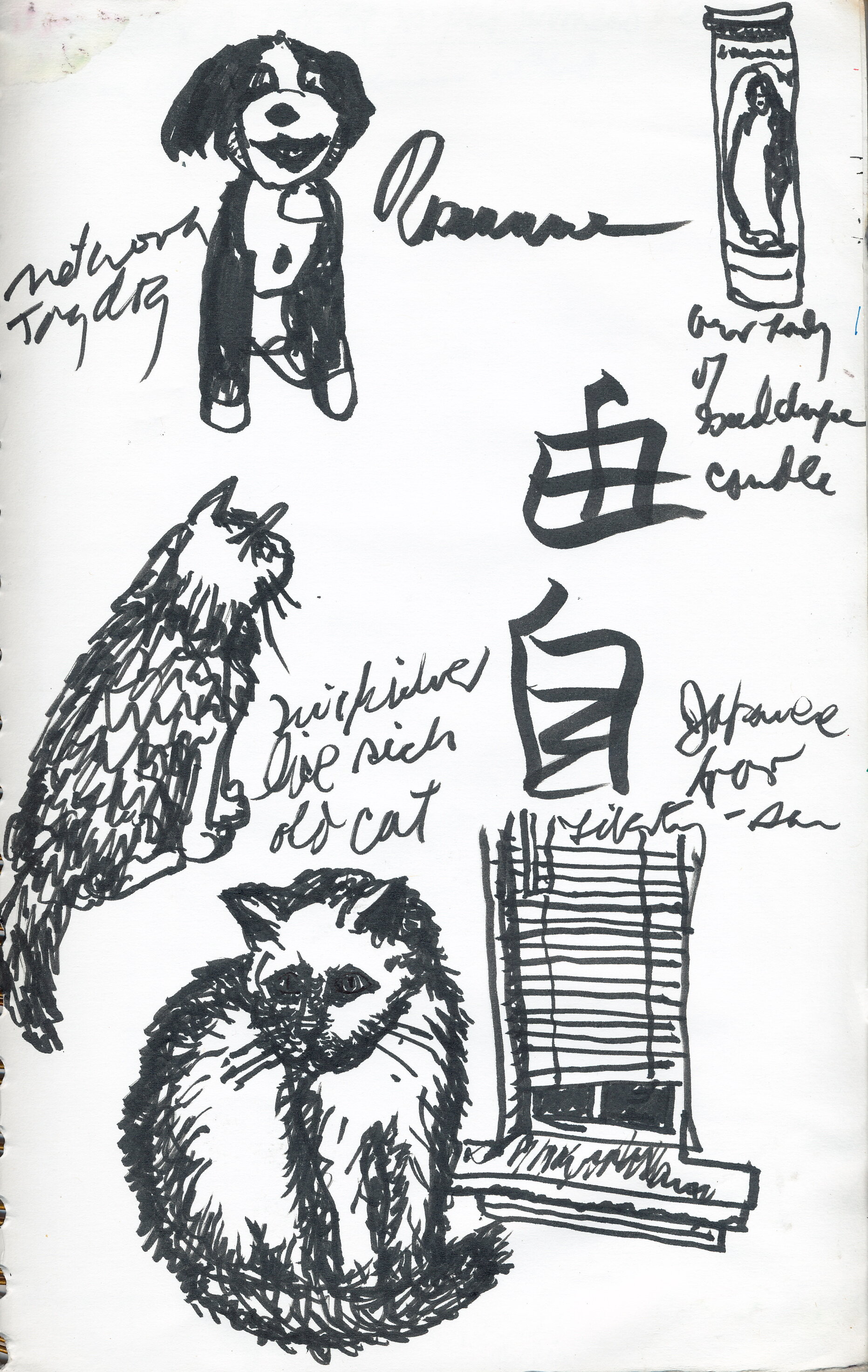

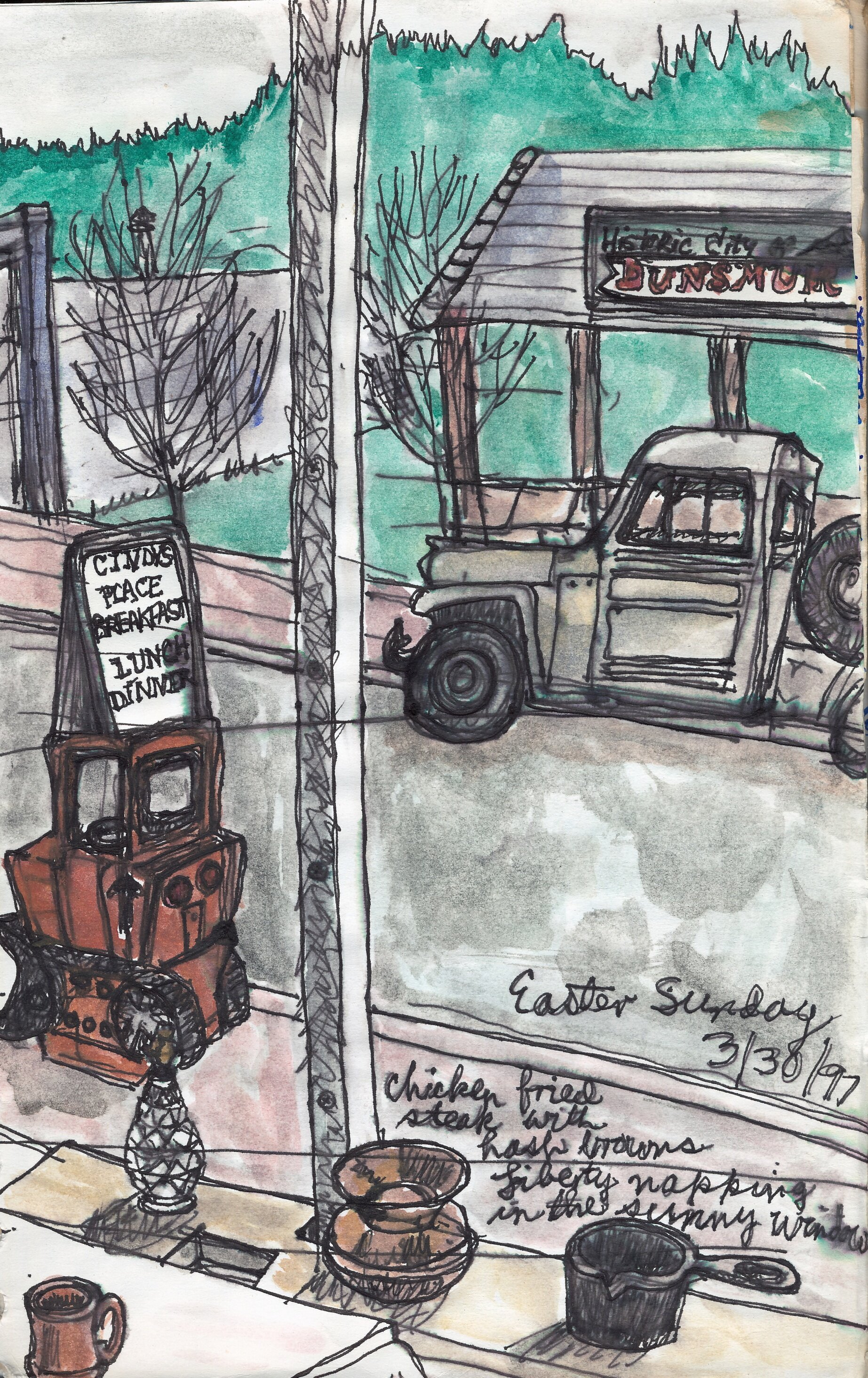

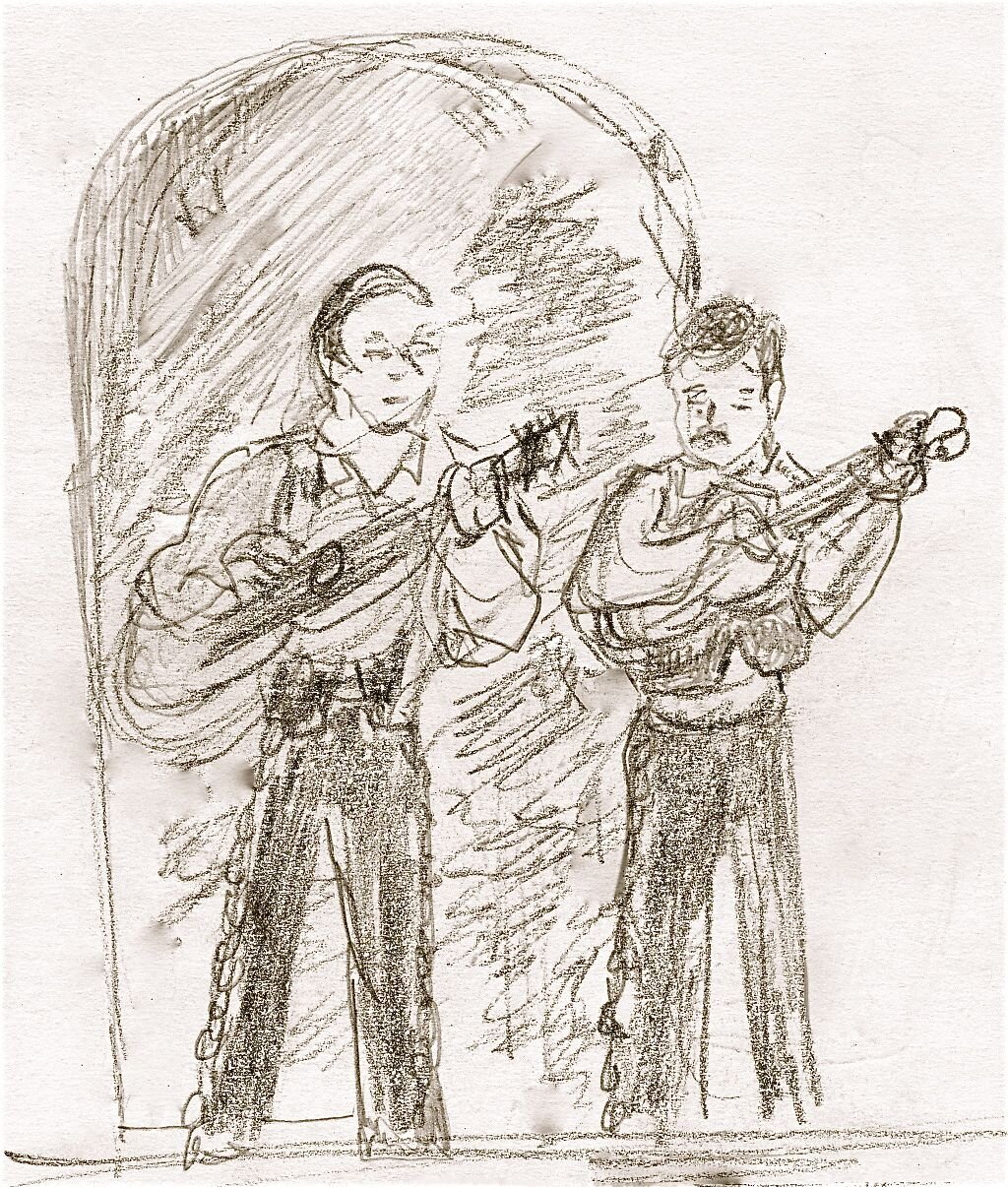

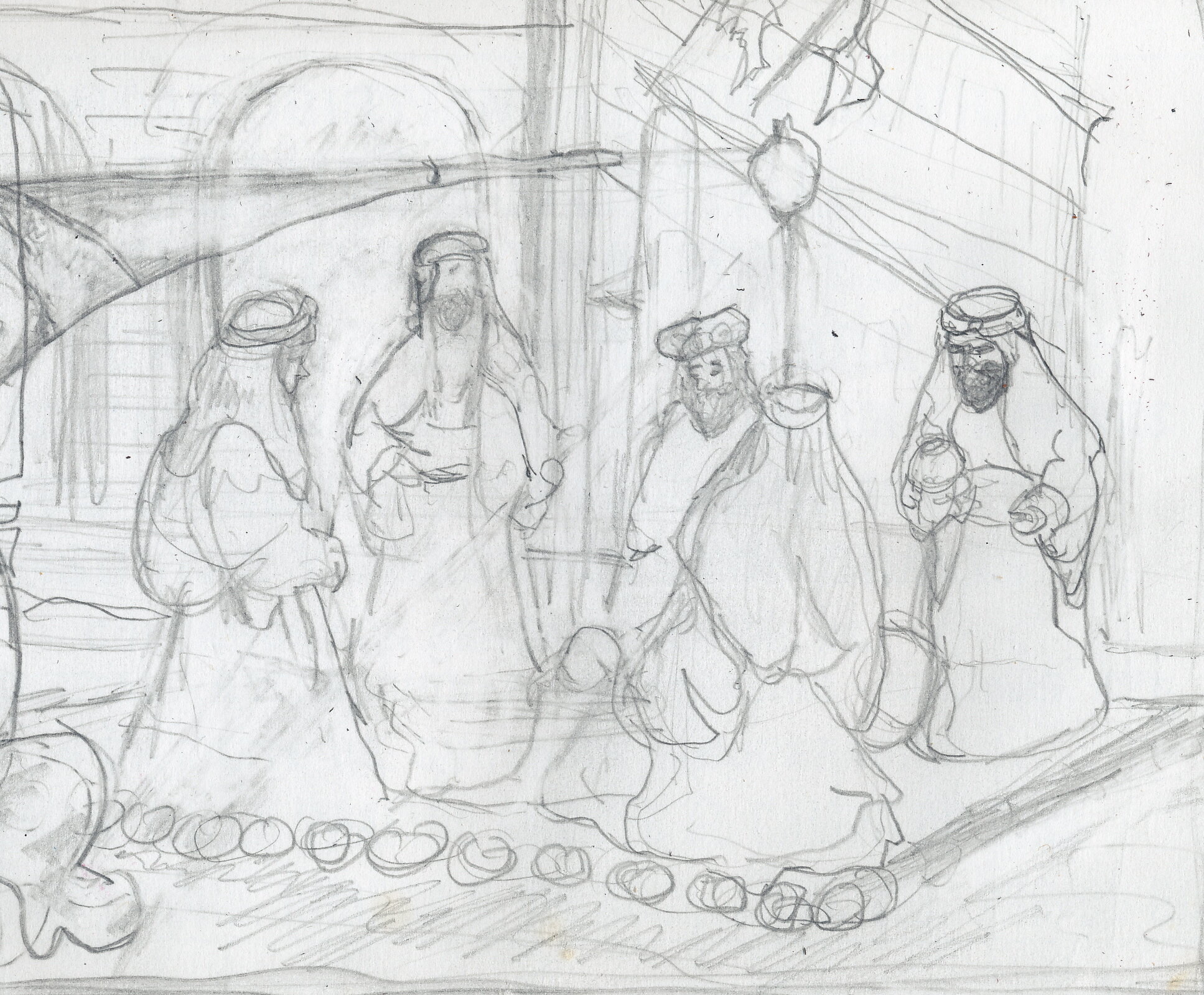

After the meal, I talked with some more children at the table and tried to communicate by showing them some sketches I had in my travel sketchbook. I also asked them their names and asked them to write them down. Yolanda was very interested in my sketches of the Milpitas car wash near where I live that is surrounded by tall palm trees, and one of a Japanese restaurant lobby in Mountain View, another of the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child from La Mision del San Carlos Borromeo de la Rio Carmel, (the Carmel CA Mission church), a sketch out of the window of funky Cindy’s Place restaurant in Dunsmuir, CA, two photos of a manger scene I took as we floated by it on a canal in Venice, and two sketches from the Fiesta Mexicana the night before.

I told Yolanda that I sometimes wish I could be a travel writer and illustrate my travel stories with my drawings and photographs, and that interested her also. Before I left, I gave a donation to the pastor and some pesos to little Anita. And even though they are seeking for converts to their particular form of protestantism, and perhaps luring many away from the Catholic Church, which I cannot approve of, I can’t help but admire the generosity and willingness of the La Viña pastors and volunteers to serve the poorest of the poor. And my prayers are still with the children that I met that day, and with Yolanda and the other volunteers.

After Yolanda and I drove back together in the front seat of the auriga to the La Viña office, as we were preparing to go our separate ways, Yolanda told me through the Englishman that even though she didn’t know me before that day, she very much enjoyed our conversation, and she hoped that somehow we could meet again in the future. Writing about that now makes me think I took part of a small miracle−in which for a brief time people from vastly different backgrounds without much common vocabulary were able to speak heart to heart.

No shortage of water back at the hotel