Art and [Moral] Ambiguity

I made a commitment (to no one in particular, but hey) to limiting myself just to writing comments in the ongoing essay exchange between Jonathan McDonald and Katy Carl, mostly because they’ve been running a pretty compelling ship already but also since there’s this never-ending, ever-growing, always-lurking pile of other potential posts I want to get around to some day – and anyway, a number of those deal with similar themes in connected contexts so it’d all come out eventually. But then I started responding to one of Walker’s comments* and things spun out of control. Thus: new post. Apologies.

As a side-note: polite, intellectually engaging comment culture = awesomesauce. Katy and Jonathan’s essays have really catalyzed us (both readers and contributors) into stepping up and making this blog more of a dialogue than a straight-up, one-way soap box. Bravo to all involved.

But onward!

For those new to the discussion, there’ve been five posts released to date on Deep Down Things (check the links above) all orbiting a nebula of related questions: how do we morally assess a work of art? What responsibility does a writer have to their readership? Under what circumstances might a piece of art do more damage than good to a person’s mind, heart or soul? How do we decide to not read/watch/listen to a book, movie or album on the grounds of potential harm it might do to us personally? And at what point would something like a ban/censorship be justified?

Katy’s recent essay took the discussion into much-anticipated concrete ground by taking some of the ideas worked through in preceding essays and applying them to Jonathan Franzen’s latest novel, Purity – the particular ideas that’ve been developed so far make up a growing list of e-words (right now we have four: explicit, exploitative, enticing and endorsing). Walker, in a few comments below her post, summarized where the debate’s currently at and applied the same concepts to two different flicks: The Shawshank Redemption and The Silence of the Lambs.

What got me writing was the language he started using: that of giving a movie metaphorical marks based on e-word criteria – he’d hypothetically pass Shawshank but might give Silence a fail (for reasons he outlined). I’m sure he was mostly being rhetorical for the sake of exploring ideas (more, please!), but it brought up a potential way of moving forward that might cause just as many problems as it solves. That being said, I think a number of these issues would mostly crop up from not really clarifying what each of these words mean and what relationship they actually have to each other.

Let’s start by looking at, for example, the first two e-words: explicit and exploitative – I feel like we’ve already established these as two fairly separate (though related) concepts, and that the only one that may have an intrinsic moral element to watch out for might be the exploitative.** But trying to make clear-cut decisions on what art’s “good” or “bad” for consumption based on exploitativeness (or author-intentions of such) is still quite dicey – Katy brought that up by mentioning her late confessor’s advice that even exploitative material doesn’t necessarily have negative moral effects so long as there’s a certain disposition on the part of the reader. At this point I agree with her – though the way one would discern what disposition would be necessary is another kettle of fish altogether.

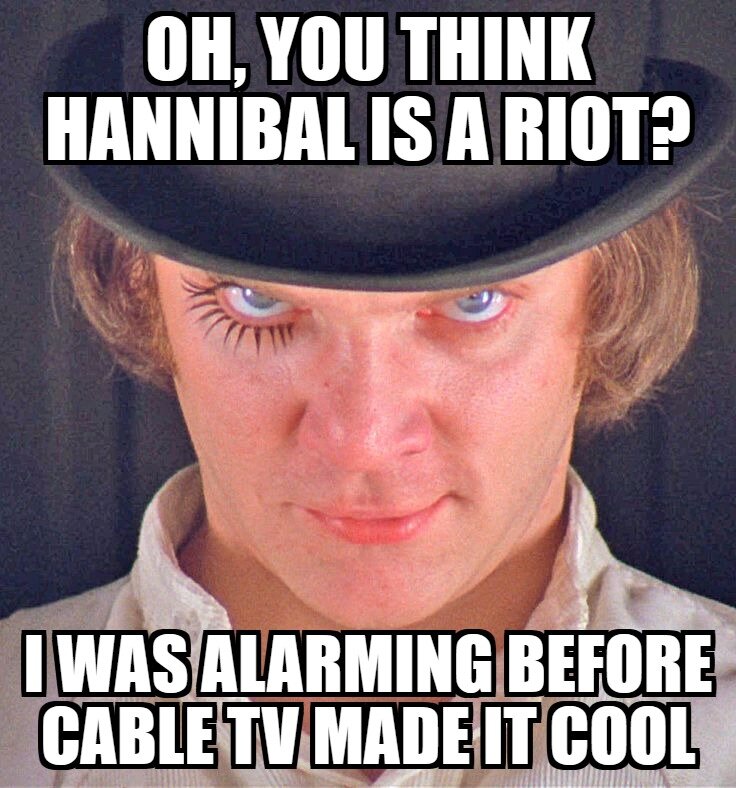

Making things even more complicated: what happens when an artist’s subject matter runs along the fault lines of the at-times incredibly subtle distinction between the two? I mentioned A Clockwork Orange (both film and book) in a previous comment and it’s coming to mind again along with (for different reasons) Tarantino’s movies.***

Clockwork, spoiler alert, is basically an old-fashioned thought experiment about the nature of free will, as well as about what we may sacrifice in the name of having secure societies – it was written by Anthony Burgess who, interestingly, struggled with the legacy of his Catholic faith for most of his creative life. His hero (if you can call him that [as he alternates between purported monstrosity and victimhood]) is Alex, a teenager in a near-future Britain whose hobbies include listening to Beethoven and committing acts of morbidly-excessive ultraviolence. Basically, he and his friends spend their evenings breaking into homes, beating old people with baseball bats and raping women in front of their loved ones. And while Alex takes it all with a sense of humour, it’s revolting to read or watch.

Our protagonist eventually goes on to be caught by the authorities and is placed in a system seeking to “cure” him of his violent impulses – the method involves subjecting him to incredibly invasive conditioning procedures. He’s basically shackled to a chair (complete with a device to make sure he can’t close his eyes [the image of him hooked up to this thing’s long become iconic]) and forced to watch clips of sickening crimes while getting zapped by electric shocks – all in hopes that, once released, he’d get nauseous and incapacitated the moment he’s tempted to steal, rape or beat anyone. This is his rehabilitation and it works.

It works indeed and it’s horrifying, though the horror’s part of the point. At the outset of the novel we’re helpless bystanders to his chaotic sprees, but then we’re caught in a place where we’re challenged to decide whether we see his treatment as fitting or too dehumanizing for even his degree of criminality. To make things even more complicated: he’s still a minor. The book/movie poses a deep moral question we wouldn’t really feel if we hadn’t been along to witness the depth of his sadism – it’s an explicit depiction that the author tries to justify (successfully, in my opinion). But it veers too close for comfort to the exploitative because, for Alex, the entire shebang is a big party and he soaks up the pleasure of every stray detail. We’re explicitly shown Alex’s (and not Burgess’s) exploitative attitude to suffering, and unfortunately the extent to which everything is shown (especially in the movie) could come off to some as exploitative itself. It’s a very thin line, and I’m sure there are people out there who do get off on watching the movie, despite Kubrick’s very clear feelings on the matter.****

So the exploitive and the explicit are not without their gray areas and, if we really think about it, that’s just part of their nature. We’ve been trying to articulate and form concrete principles these past few months, but this’s been hard as we’ve constantly been confronted with how art (much like people/the relationships between them) doesn’t fall easily into equations of “this + that = a good/bad thing for me.” So much here, again, depends not only on an author’s intent but also on the critical capacity of a culture (or sub-culture, as practicing Catholics are these days); focusing on educating ourselves/others in terms of *how* to read rather than what to read might be key to that. Obviously that’s an ideal, though, and we’re still far from that reality – any practical response we come up with has to take into account the facts of where we are, as compared to focusing nigh-exclusively on the dream of where we’d like to be.

I think it’d also be good at this point to try to clarify what exactly we’re trying to do here by applying these e-words: are we looking to justify why we keep coming back to (and are fed by) art that makes us morally uncomfortable? Are we looking to see (and define) the value of this kind of art in the face of movements that may reject it as something unfit for aesthetic consumption? Are we trying to define a concrete situation where we feel there could be an outright, unapologetic ban on a book, movie, song or image? Are we trying to sort out the kinds of moral culpability that apply to artists and their audience? While most of what’s being written in this vein has been deeply compelling, I wonder if we’re kinda losing sense of what it is we’re trying to figure out, and why we find the categories of explicit and exploitative to be relevant lenses through which to view art.

The second pair of e-words, enticing and endorsing (by which we mean titillation and glorification, yeah?) seems to focus in on the ways art could influence a person to, from a Catholic perspective, sin. On the one hand, this’s something that someone could easily support banning in the name of prudence: if it has the ability to harm someone, why allow access? Even flirting with the line could be seen as putting oneself in the near occasion of sin. Murky moral ground indeed. But while it might pose certain complications for the reader,***** I’d still hesitate to make the claim that it constitutes grounds not to read something at all. Again, to risk sounding like a broken a-track, so much depends on the reader and their state of mind, heart and critical awareness. That all being said, I’d be interested in hearing a case being made for “the book no person should read” as I think it might clarify some elements in this discussion. Does anyone want to tackle that? What works could be classified like this?

All that aside, even if a book is enticing/endorsing something Catholics can’t morally get behind, it’s still not a clear-cut case of “THIS IS BAD, WATCH OUT” – a person typically makes something enticing/endorsing when they sincerely believe the things they’re writing about are objectively true and a necessity for the world. And when someone goes through all that trouble then there’s usually something we can learn from it, maybe even something we ourselves don’t spend enough time thinking about

When enticingness was brought up in the essays, people were mostly (implicitly or explicitly) referring to sex – it’s a big topic when talking about censorship in general. It’s an obvious starting point to launch into this particular e-word, as presenting something with even slight sexual overtones can provoke really strong responses in some folks – it’s something people can easily claim, again in the name of prudence, should be heavily regulated (or banned) in art mostly for the fact that it could make it hard for someone to live the church’s call to chastity. Which could lead to a mindset of “if a movie shows this much skin or goes too far in showing sex, it crosses the line and shouldn’t be watched by Christians.”

To explore that thought, I want to talk about a film that feels a little funny to be bringing up on a Catholic website, as it’s definitely explicit, enticing and endorsing (though never exploitative) in a sexual sense: Shortbus. In short, it’s basically about an apartment in New York where orgies take place and the film follows a number of characters who, for different reasons, frequent it.

Before going on, I gotta say that this isn’t an all-out recommendation of the film. And I’m not claiming it was necessarily a good idea to make a movie like this – analyzing that would take a whole post (or series) of its own. I will say, however, that the filmmakers seemed to make it for the purpose of actually legit exploring sexuality – and not in the sense of when a TV channel or movie advert screams “we’re exploring sexuality!” when they actually mean “hey, check out these breasts” (HBO, anyone?). John Cameron Mitchell (the director), as it turns out, is more concerned with the emotional impact of sex, relationships and the senses than with penises and vaginas (though there happen to be plenty of both), and has been quoted as wanting to explore sex on screen in a de-eroticized way so as to get at the kernels of the human experience that’re excluded by the gaudiness/exploitativeness of porn. The movie shows everything (people aren’t even faking sex in the film – they’re actually having sex) because the filmmakers find there’s nothing to be ashamed of or hide – this isn’t maliciousness or shallow exploitation…they know what they’re doing and deeply believe it needs to be done. There’s no manipulation in the common sense of the word, just the logical conclusion of a mindset that exists around us today.

This film presents a difficult case for analysis, as it not only promotes lifestyle choices that go against church teaching on sexuality, but the imagery itself might actually cause the person to, from a Catholic outlook, sin right then and there. But again (broken record!) I think it depends on the person and their approach to the film – if I’m honest, I didn’t feel aroused by it. The film was definitely promoting what we consider to be sin, but because it a) resisted the exploitative and b) found the human roots of the characters’ journeys, it could be argued that merit could be found in watching it. It’s not Fifty Shades – the director himself has been quoted as wanting to “remove the cloud of arousal to reveal emotions and ideas that might have been obscured by it.” I feel like I learned a few important (and poignant) things, even though they were mixed in with stuff I don’t believe. And these were things I don’t think would’ve been touched on in a slightly tamer rom-com. That’s not to say, though, that one couldn’t learn those things without watching the film. And it wouldn’t be everyone’s experience watching it either – like, for a given person, it could really be a disaster. But then again for someone else it might constitute a word desperately needing to be heard. Or maybe it was just a bad idea altogether. Thing is, though, institutions like the Index weren’t built to address this kind of nuance – it was meant to be a blanket set of recommendations across the board. How, moving forward in its absence, do we build structures able to deal with subtleties like this? Is it even possible?

That being said, though, while it’s really easy to get overly tied up (not without reason) in the whole sexual element of the enticing-endorsing thing, it’s not the exclusive (or even most potentially sketchy) case here – it’s just happens to be the most obvious.****** It’s much easier to ignore books, movies, songs or images making compelling intellectual and emotional cases against the church – I’m thinking here about Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy (the first one was made into a film) and Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael. They were both incredibly popular and made direct accusations against the church, followed up by calls to reject and move beyond it.

His Dark Materials might be best summed up as a counter-Narnia, one in which a compelling and emotional story unfolds that literally has the main characters embracing the fall and making war against heaven in hopes of killing God. I am literally not making any of this up – in Pullman’s worldview, the Christian perspective is a half-formed perversion of truth that demands to be overcome. To that end he created a painful, original, beautiful story in which children team up with fallen angels to take down the universe’s biggest tyrant (aka, YHWH), all for the sake of the world

Intellectually (and emotionally) it’s both enticing and endorsing – Pullman makes a case and pulls at your heartstrings in equal measure. His writing, plot and characterization are so powerful that, even if you’re not on board with his metaphysics/worldview, you’re still irrevocably swept up – and he makes it very, very easy to get on board with the whole deicide shindig. Would it have landed on the Index? You can bet your golden compass on it. Does it have value regardless? Absolutely. While reading it for a university class, I was smacked upside the face by stunning images and wholly inspired as both writer and storyteller – I felt myself growing as a reader and a person. Yes, to me the final scene was more than a slight cheap shot and ended up wounding me (not in a fun or positive sense) in a way I’ve never experienced before or after in literature. But even if it frustrates me beyond end, it is utterly a work of art. Damn fine art at that.

This could be contrasted with a book like Ishmael – as compared to the subtle and extensive aesthetic pleasures of His Dark Materials, this one is more of a didactic dialogue that should’ve been an essay. It’s a bit of a gimmicky book, even if there are beautiful parts to it that are downright fascinating to read. Which is interesting, because it (and its sequels) are basically about someone talking to a gorilla who tries to convince people (the reader included) to become an antichrist.

Yes, cue the freak-out, but let’s take it in context here: the writer believes that humans, way back when, created problems that spiraled out of control – accordingly, we needed a saviour. So then we, apparently, made up the idea of a saviour, Christ. The author isn’t against Jesus as a person, but believes the idea of needing a saviour has brought about countless tragedies and wasted lives. To cling to him, in this worldview, is to cling to the old paradigm that made Jesus “necessary” in the first place. So the idea to become antichrist is the thought of going to the root sources of our problems (which, to the author, isn’t about concupiscence or the fall so much as how we relate to the earth, agriculture and each other) and solving them.

As contrasted with Pullman’s work, Quinn’s (taking the oft-traveled [particularly by many Christian authors] road of bashing a message over the reader’s head with the subtlety of a garbage truck) is no staggering work of heartbreaking genius. From an aesthetic point of view there isn’t as much value to the reader, and so leaving it ignored is hardly going to diminish the culture. But, even in a book like this (antichrist-y ambitions and all), the arguments from a place of compassion and and genuine desire to make the world a better place. And, from a standpoints of ideas, even if they more-than-slightly presumptive, the experience of reading it is undeniably moving – the book’s enticing and endorsing of a mindset that Christians, by believing in Jesus/grace/salvation/the whole package, resist wholeheartedly. But it’s neither explicit or exploitative, and it’s a valuable text in terms of understanding a specific worldview. Reading it holds the risk, for someone still struggling to understand what Christianity suggests about the world (regardless of age), of accepting an opinion of the church that doesn’t jive with what it actually says about itself. The way it’s written makes it anything but a neutral experience. There were a number of things that tugged at my heart while reading it, which made for a painful experience of the sort you get when you see someone important to you being deeply, deeply misunderstood. And I can completely understand if that sort of pain’s reason enough for someone to decide not to read a particular book.

Both books reject popular Christian interpretations of the fall: Ishmael sees it as the human decision to begin dominating the earth (or, in the book’s lingo, being a “taker” instead of a “leaver”), while His Dark Materials goes so far as to claim the fall was probably one of the best things to ever happen to us as a species. Both try to make an engaging case against a Christian worldview through art – it’s not done out of maliciousness but with the best of intentions and we need to be aware (and thankful, in a way) for that. Response to art like this can involve an outright ban or boycott in the name of protecting minds (that legit could be influenced) or, conversely, call for an attempt to critically engage with it.******* But, while engaging with art seems like an obvious good choice, it’s been mentioned on this blog before how difficult it is to raise the critical awareness of a culture. Again, we have to deal with realities rather than with ideals, even though we don’t really know yet just how to do that.

But imagine if we moved towards equipping people with the tools to engage with this kind of stuff? Imagine if Catholic lit courses taught both of these books from a critical perspective? What if we started challenging people to judge the worldview of a piece of art critically instead of assuming we just mindlessly imbibe what we read (which, to be fair, does happen on occasion [though, granted, it’s a tad more complicated than that])? But again, these questions deserve posts all their own.

Bringing things back, I guess I just want to say the four e-words might better be served as lenses for analysis rather than checkmarks on a list to pass/fail a work of art, or to judge whether it should be banned or boycotted. I think they’re just a good way to describe whether a work falls into a category let’s call, for lack of a better term “morally ambiguous” for its potential to lead a person into sin. I would say that A Clockwork Orange avoids this altogether even if it’s content matter can really scar a sensitive reader/watcher. But art that solidly lands in this category still varies greatly in terms of how Catholics can respond: Shortbus and His Dark Materials happen to be powerful works that have the capacity to feed particular, dry parts of your soul. Ishmael, even if it doesn’t reach the depths necessary to really enrich a person, contains ideas that appeal profoundly to humane parts of a person.

So what’s the point of all this? It all comes down to asserting the value, even if just to a limited number of people, of works of art that raise very, very red flags in our ever-forming list of e-word criteria. I could waste exorbitant amounts of ink with a close reading of these four titles, but in the end I’d conclude by simply arguing that blanket bans, even if it did protect certain minds/hearts/souls, would still deprive the world of something – maybe even something beautiful.

Where can we go from here? I guess some questions still remaining include: how does one discern whether a morally ambiguous work of art will help or hurt you? How do you decide whether to recommend art like this? If, in some parallel universe, the church was in charge of book presses and movie studios around the world, would it be more harmful or helpful to limit access to morally ambiguous art? How much moral ambiguity is too much? How can we challenge people to be able to pick things apart for themselves so as to take the metaphorical meat and leave the bones? Even if we can master that, what risks might still be involved?

I’m very interested in seeing where this conversation goes.

—

*The response was to a particular note found mid-way through the comment section of Katy’s engagement with Jonathan Franzen’s Purity – it starts with “I need to be careful myself about not confusing recommendation with what I think the four e’s are about, our provisional scale for evaluating moral harm that could be done by a work to an ‘average adult’ (not kids or the scrupulous).”

**Jonathan expressed some reservations about giving explicitness a free pass, and I’d love to hear more from him about that.

***As an aside, an analysis of Tarantino’s work on this front would be quite fascinating.

****Interesting factoid: the original text of Burgess’s novel included a final chapter where Alex eventually grows to reject his past and stop feeding his violent impulses, but the chapter was cut from the original publication in America and, thus, from Kubrick’s film. The one-chapter-less novel and the film end with Alex resisting his conditioning, but it stops short of his eventual turn toward empathy and active citizenship.

*****So, in the interests of not having to say “the reader/listener/watcher/audience,” I’ll just stick to the language of authors and readers. Yes, it’s not the most accurate way of doing it, but we don’t really have a general word in English for someone who engages with art other than the plural noun “audience,” and it doesn’t really cut it here.

******And, as the most obvious, the most regulatable.

*******For an related (though personal) exploration of the relationship between boycotting and engaging with challenging art, check out the “Beyond the Spotlight” posts from a month ago.